|

|

|

|

Therapeutic Avian Techniques

Don J. Harris, DVM

Avian & Exotic Animal Medical Center

Miami, FL

Air Sac Cannula

Tracheal obstructions from foreign bodies, neoplasia, fungal granulomas, etc. initially require the creation of an alternate breathing passage. The existence of the air sac system in birds provides a means of ventilation not possible in mammals. Effective respiration can be achieved by intubating the caudal thoracic air sac.

Anesthesia is helpful in birds that are capable of resisting restraint. Those which are severely dyspneic may offer little resistance and the need to establish effective ventilation may preclude anesthesia.

|

Fig. 1

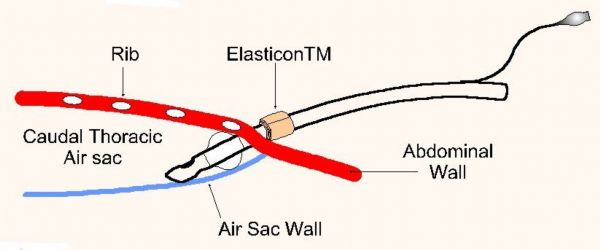

The type of tube utilized depends on the size of the patient and the urgency of the situation. In small birds a 2-3 cm section of I.V. tubing will suffice. In larger birds a standard 3.0 mm I.D. cuffed endotracheal tube can be modified for abdominal installation. The tube is trimmed just above the air line thereby preserving the integrity of the cuff. A 1 X 5 cm strip of Elasticon™ is wrapped around the endotracheal tube 2-3 mm above the cuff. Inflation of the cuff after placement in the bird offers the advantage of securing the tube in place and more importantly expanding the air sac thereby improving the patency and effectiveness of the tube (figure 1).

The breathing tube can be installed into the caudal thoracic air sac either between the last two ribs or just behind the last rib, both just dorsal to the dorsal edge of the pectoral muscle. The patient is secured in lateral recumbency and the area is surgically prepped. The leg is flexed and abducted (not pulled cranially or caudally) to expose the last rib. A stab incision is made through the skin with the point of a #15 scalpel blade. A fine mosquito hemostat is used to bluntly dissect through the intracostal or abdominal muscles forming a hole barely large enough to insert the breathing tube. The tube is inserted and secured either by suturing or inflating the cuff, or both. Patency can be tested by holding a microscope slide at the opening to observe for breathing induced fogging. Once secured, the bird can breathe freely through the tube or an air line can be connected for oxygen administration or anesthesia.

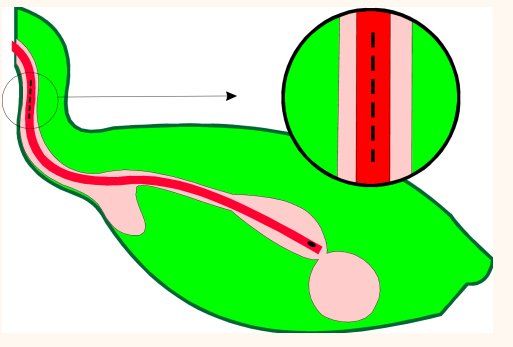

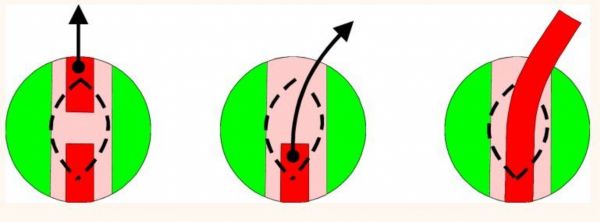

Esophagostomy Feeding Tube

Certain situations mandate bypassing the crop and depositing food directly into the proventriculus. Babies suffering from crop burns or those with refractory crop dysfunction, and birds with severe beak injuries benefit greatly from an indwelling proventricular feeding tube installed via an esophagostomy. A 14 French red rubber feeding tube is passed down the esophagus of an anesthetized bird, manipulated through the crop and into the thoracic esophagus, and continued to the proventriculus until resistance is felt. At that time a 1 cm longitudinal incision is made on the right side of the neck over the feeding tube identified within the esophagus (figure 2). The tube is isolated and transected beneath the incision, the oral end is removed completely, and the proventricular end is extracted 2-3 cm from the incision (figure 3).

|

Fig. 2

|

Fig. 3

A 1x5 cm strip of Elasticon™ is wrapped around the protruding end of the feeding tube and it is sutured in place on the neck. If the incision is large, it may be sutured, but typically suturing is not necessary. A male adapter plug can be used to cap the tube between feedings. This device has been left in place as long as seven weeks without complications. Removal is accomplished by simply cutting the stay sutures and extracting the tube. Debridement and surgical closure of the wound has not been necessary.

Intraosseous Catheter- Ulna

Because of the difficulty in stabilizing a standard I.V. catheter and the small size of many patients, the intraosseous catheter has become popular in avian practice. Two primary sites are used: the distal ulna and the proximal tibiatarsus. The technique simply involves installing a spinal needle through the end of the bone and into the marrow cavity. The femur and humerus are not used because of their pneumatic properties.

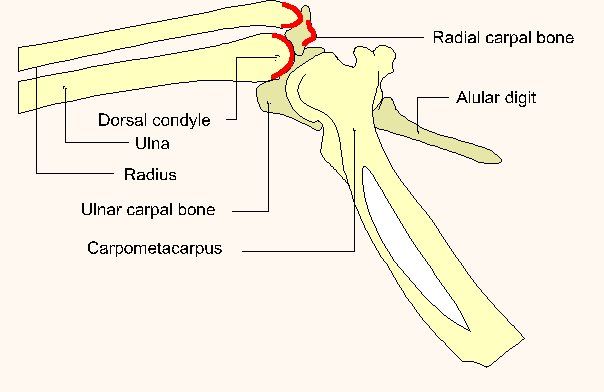

When utilizing the ulna, a triangle is identified as formed by the dorsal condyle of the distal ulna, the distal radius, and the radial carpal bone (figure 4). The carpus is flexed and the ulna is identified by palpation. The most important landmark to be identified is the dorsal condyle of the distal ulna. It is behind this structure that the needle is inserted. Once the insertion site is located a surgical prep of the area is performed. The needle is directed under the dorsal ulnar condyle and proximally into the shaft of the ulna. The needle is seated then the stylet is withdrawn and the needle is capped and secured with tape or stay sutures.

|

|

Fig. 4 (Publisher's note: Original figure was divided into two parts to better fit your display.)

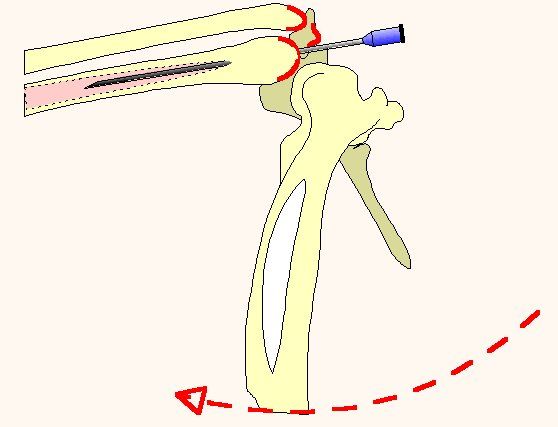

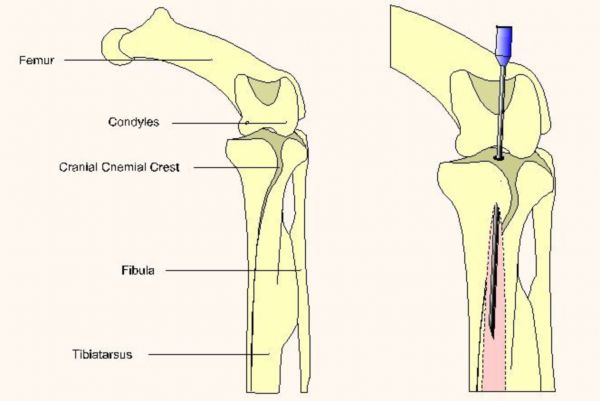

Intraosseous Catheter - Tibiatarsus

The approach to the tibiatarsus is similar to that for a normograde pinning of the bone. The cranial cnemial crest is identified on the anterior aspect of the proximal tibiatarsus between and just distal to the femoral condyles (figure 5). The area is prepared for sterile technique and the spinal needle is directed into the tibial plateau just posterior to the cnemial crest and distally into the marrow cavity of the tibiatarsus. The stylet is withdrawn and the hub is then taped or sutured in place.

|

Fig. 5

With either technique fluids should be administered especially slowly to avoid leakage (minimal with careful technique) and pain (significant with high pressure).

Intravenous Administration

Fluids can also be administered directly intravenously as in other species. Standard I.V. catheters can be utilized in larger birds although catheters have routinely been installed by the author in the jugulars of patients as small as 75 grams. Birds as small as 15 grams can be administered fluids with single boluses given via the jugular. The basilic and medial metatarsal veins may be used in larger birds. In some cases one or two boluses provide such improvement that further I.V. administration is unnecessary.

Use of the basilic vein usually results in the formation of a large hematoma at the administration site. This can be minimized by removing the needle from the vein but not the skin following fluid administration and injecting a large volume of fluids subcutaneously. The fluid compression then lessens vascular leakage.

Jugular Catheter

Installation of an intravenous catheter is easily accomplished in many species of birds. The more prominent right jugular and often the left jugular are readily accessible on the ventrolateral sides of the neck. A standard I.V. catheter of appropriate size and length is installed into the jugular in a cardiac direction. It is important to place the catheter as near the thoracic inlet as possible to avoid kinking when the neck is in normal flexion. Use of a more rigid polypropylene catheter also minimizes the possibility of kinking. The catheter can be sutured in place or enclosed in a tape collar following installation. The tape collar actually increases the catheter's stability but should be applied loosely to avoid constricting the crop and esophagus.

|

|

Copyright ACVC