The normal third eyelid or nictating membrane sits in the inner corner of the eye. This shows a cat's normal third eyelid but the structure is basically the same in dogs. Photo courtesy of MarVistaVet

Prolapse of the Tear Gland of the Third Eyelid

Unlike humans (who have two eyelids), dogs and cats have three. The third eyelid, called the nictitans or nictitating membrane, arises from the inner corner of the eye and covers the eye diagonally as shown. Its purpose is to further add moisture and protect the eye.

The eye is lubricated by the tear film, which consists of water, oil, and mucus. The oil comes from glands lining the outer eyelids, the mucus from glands in the conjunctiva (the pink part inside the eyelids), and the water from the tear (or lacrimal) glands. Each eye has two tear glands: one just above the eye and one in the third eyelid. The gland in the third eyelid is believed to produce 30 percent of the total tear film water, so it is important to maintain the function of this gland.

The third eyelid's tear gland is held in place by tissue fibers, but some individuals have weaker fibers than they should, so the gland protrudes. This protrusion is called a cherry eye. In the smaller canine breeds, especially Boston terriers, cocker spaniels, bulldogs, and beagles, the third eyelid gland is not strongly held in place because of genetics. The gland prolapses (drops down or protrudes) to where you may notice it as a reddened mass. Out of its normal position, the gland does not circulate blood properly, may swell, and may not produce tears normally.

Treatment: Replacing the Gland to Its Proper Location

Tucking or Tacking

The best treatment for cherry eye is replacing the gland in its proper location. There are two techniques for doing this. The traditional tucking method (also called tacking) is the most commonly performed. A single stitch is permanently placed, drawing the gland back where it belongs. Complications are uncommon, but be aware of the following possibilities:

- If the stitch unties, the suture could scratch the eye's surface. If this occurs, the eye will suddenly become painful, and the suture thread may be visible. The suture can be removed, and the problem solved.

- The tuck may not be anchored well enough to hold permanently. This surgery is notorious for this type of failure, and a second or even third tuck is frequently needed. If more than a couple of tucks have led to failure, it may be better to try the imbrication technique described below. Some cases are repaired using both tuck and imbrication.

- Sometimes, the cherry eye is accompanied by other eyelid problems that make the repair more difficult or less likely to succeed. In these cases, again, if the simple surgery is not adequate, ask your veterinarian if a referral to a veterinary ophthalmologist for the second surgery to maximize the chances of a permanent resolution is in the best interest of you and your pet.

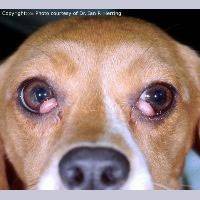

A dog with cherry eye in both eyes. Photo courtesy of Dr. Ian Herring

Imbrication

A second surgical technique is called imbrication, or pocketing. A pocket is formed from nearby tissue to hold the gland. The technique is more difficult and requires specialized equipment. Tiny dissolvable stitches are used to close the pocket. Complications may include:

- Inflammation or swelling occurs as the stitches dissolve.

- Inadequate tightening of the tissue gap may lead to a recurrence of the cherry eye.

- Failure of the stitches to hold and associated discomfort. Depending on the type of suture used, loose stitches could injure the eye.

Both surgical techniques are sometimes used in the same eye to achieve a good replacement. Harmful complications from cherry eye surgery are unusual, but recurrence of the cherry eye can happen. If it recurs, it is important to let your veterinarian know so that a second surgery, either with your veterinarian or an ophthalmologist, can be planned.

Expect some postoperative swelling after cherry eye repair, but this should resolve, and the eye should be comfortable and normal in appearance after about a week. If the eye appears suddenly painful or unusual in appearance, have it rechecked as soon as possible.

Removing the Gland and Treatment

Removal of the gland is generally avoided if possible, and it is only removed if it has been exposed for an extended period of time, if previous surgeries have failed, or if the eye/gland has additional problems. The reason to keep the third eyelid gland is that if the other tear gland (the one above the eye) cannot supply adequate tears, the eye becomes dry and uncomfortable. This is not uncommon in senior dogs.

A thick yellow discharge results, and the eye develops a blinding pigment covering for protection. This condition is called dry eye or keratoconjunctivitis sicca. Daily medical treatment is required to keep the eye comfortable and preserve eyesight. Not only is dry eye uncomfortable, but treatment can be frustrating, time-consuming, and lifelong. If left untreated, the eye can become blind.

Veterinarians strongly recommend that pets maintain the most tear-producing tissue possible, so removing the gland for cosmetic reasons is not an acceptable treatment.