A. Granger

Veterinary Clinical Sciences, School of Veterinary Medicine, Louisiana State University, Baton Rouge, LA, USA

Overview

Icterus in the dog has multiple potential underlying causes, many of which are diagnosed with imaging (ultrasound, radiography, and computed tomography). Specifically, the methods to complete an imaging diagnosis of icterus in the dog, with emphasis on ultrasound, will be discussed.

Causes of Icterus in the Dog

Table 1. Causes of icterus

|

Pre-hepatic

|

Hepatic

|

|

Hemolytic anemias:

|

Hepatitis—chronic

|

|

- Primary immune-mediated hemolytic anemia

|

Hereditary hepatitis (breed-specific)

|

|

- Idiopathic

|

Drug-induced (phenobarbital)

|

|

- SLE

|

Hepatitis—acute

|

|

- Blood transfusion

|

Toxic (e.g., NSAID)

|

|

- Paraneoplastic hemolytic anemia

|

Infectious (leptospirosis, canine infectious hepatitis, Yersinia, Salmonella)

|

|

- Lymphoma

|

Neoplasia

|

|

- Hemangiosarcoma

|

Lymphoma, mast cell tumor, hepatic

|

|

- Infection-induced hemolytic anemia

|

|

|

- Piroplasmosis, dirofilariasis, bacterial endocarditis, leptospirosis, ehrlichiosis, sepsis

|

|

- Toxin-induced hemolytic anemia

|

|

- Onion, zinc, methylene blue, sulphonamides, copper, penicillins/cephalosporins

|

Once pre-hepatic causes of anemia are ruled in or out, distinguishing the remaining causes of icterus as hepatic or post-hepatic is very imaging intensive with ultrasound being the primary modality used.

Table 2. Specific organs to isolate on ultrasound examination for causes of hepatic or post-hepatic icterus

|

Organ to evaluate

|

Specific diagnoses

|

|

Liver

|

Hepatitis, neoplasia

|

|

Gallbladder

|

Cholecystitis, mucocele, gallbladder rupture

|

|

Bile duct, hepatic ducts

|

Biliary obstruction, cholangitis

|

|

Pancreas

|

Pancreatitis causing obstruction

|

|

Pancreatic neoplasia causing obstruction

|

|

|

Duodenal papilla

|

Nodule or mass causing obstruction

|

Hepatic Diseases Causing Icterus

Diffuse Abnormalities of Hepatic Echogenicity

Many of the diseases that may cause icterus are diffuse in nature. As a result, rather than finding focal masses or nodules, an overall alteration in hepatic size and/or echogenicity may indicate disease.

Table 3. Common differential diagnoses for diffuse changes in hepatic echogenicity

|

Diffuse hyperechogenicity

|

Diffuse hypoechogenicity

|

|

Steroid hepatopathy

|

Passive congestion

|

|

Lipidosis

|

Acute hepatitis or cholangiohepatitis*

|

|

Other vacuolar hepatopathies

|

Lymphoma*

|

|

Chronic hepatitisa*

|

Leukemia

|

|

Fibrosisa*

|

Histiocytic neoplasms*

|

|

Cirrhosisa*

|

Amyloidosis

|

|

Lymphoma*

|

|

|

Mast cell tumor*

|

aOften have concurrent microhepatia (the remaining differential diagnoses can occur in normal or enlarged livers).

*Most apt to cause icterus.

Hepatitis

The ultrasonographic appearance of acute and chronic hepatitis differs, classically. Acute hepatitis, if abnormalities are visible, tends to create a mildly enlarged liver that is diffusely hypoechoic. Chronic hepatitis will create hepatic hyperechogenicity. The ultimate diagnosis of hepatitis and distinction between forms requires clinical history and tissue sampling.

Dogs with acute hepatitis typically have hepatomegaly (although a normal sized liver is possible) and inflammatory cells, hepatocellular apoptosis, necrosis, and regeneration would, in varying degrees, be reflected in tissue sampling. A hallmark of chronic hepatitis is the addition of fibrosis to the mononuclear or mixed inflammatory infiltrate, hepatocellular apoptosis, necrosis, or regeneration. Cirrhosis is the end-stage result of hepatic fibrosis with a small and irregular liver. Concurrent peritoneal effusion can be present due to the presence of portal hypertension and vascular derangement.

Hepatic Neoplasia

The most common neoplasms to cause icterus are infiltrative and metastatic neoplasms. Infiltrative neoplasms are usually round cell tumors that cause enlargement and a diffuse change in echogenicity. Lymphoma is the most commonly encountered infiltrative neoplasm of the liver and it typically causes a diffuse hypoechogenicity.

Metastatic neoplasms are about 2.5 times more likely to occur than primary hepatic neoplasms such as hepatocellular carcinoma.1 Often metastases originate from the spleen, gastrointestinal tract, and pancreas. Metastatic lesions within the liver are often nodular in appearance. Many benign lesions within the liver can also create a nodular appearance (e.g., nodular regeneration). Targetoid nodules are more indicative of malignancy and can be found within the liver or spleen and may be due to metastatic or primary neoplasia but are often found with metastatic disease.2 A targetoid nodule is a typically hypoechoic nodule having a hyperechoic center. Ultimately, tissue sampling of the nodules and surrounding tissue must be obtained to confirm malignancy.

Biliary System

The gallbladder, located between the quadrate and right middle liver lobes, should be anechoic or a layer of sludge can be visible in asymptomatic dogs.3 The gallbladder wall should be nearly invisible measuring no greater than 3 mm in thickness. Occasionally, a normal bile duct can be identified; the normal bile duct in a dog should not measure greater than 3 mm in diameter. The bile duct is ventral to the portal vein and may be slightly to its right. The intrahepatic biliary system, including hepatic ducts, should never be visible. The key landmark for locating the common bile duct is identification of the major duodenal papilla just aborad to the cranial duodenal flexure.

Biliary Diseases Causing Icterus

The most common diseases of the biliary tract causing icterus are due to primary gallbladder diseases (gallbladder mucocele or cholangiohepatitis), or obstruction or infection of the common bile duct (cholangitis). Of all dogs presenting for gallbladder disease requiring surgery or resulting in necropsy, about 47% were icteric.4 A significant relationship exists between gallbladder necrosis and gallbladder rupture. Dogs with gallbladder rupture tend to be icteric and rupture can occur secondary to a mucocele, infected bile (cholecystitis), or idiopathic wall necrosis and rupture without concurrent infected bile or mucocele.4

Cholecystitis and Mucocele

Cholecystitis may not be sonographically visible. If evidence does exist, a thickened gallbladder wall may be seen (>3 mm). Sometimes luminal gas can be identified in the gallbladder. Cholecystitis leading to gallbladder wall rupture can be a sequela of infected bile. However, gallbladder wall necrosis without concurrent infection or mucocele can also occur for unknown reasons. About 50–75% of dogs presenting with a gallbladder mucocele will have concurrent rupture due to wall necrosis;4,5 however, the presence of a mucocele can be an incidental finding. A gallbladder mucocele appears as an irregular anechoic rim at the inner margin of the gallbladder wall of variable thickness and, often times, a hyperechoic center of hyperechoic luminal sludge material.

Gallbladder Rupture

The primary indicator of rupture is regional changes within the liver or peritoneum.4,5 A large volume of effusion is rarely present with gallbladder wall necrosis and rupture. Often times, only a small rent is present in the gallbladder, which is rarely visible on ultrasound unless a mucocele can be identified protruding from the wall.4 A variable echogenicity change within liver surrounding the gallbladder and hyperechoic mesentery in the region of the gallbladder are the most reliable indicators of gallbladder rupture. Often times mesentery in the right cranial abdomen is also hyperechoic.

Dilated Common Bile Duct

A dilated common bile duct is most often seen with extrahepatic biliary obstruction. This is most often caused by a concurrent pancreatitis, although luminal obstructive material (sludge or a choledocolith) or extramural mass associated with the duodenum or pancreas can also cause obstruction. A dilated common bile duct is expected within 48 hours of obstruction. Intrahepatic biliary duct dilation is evident 5–7 days after obstruction of the common bile duct.6,7 Dilation of the intrahepatic biliary system appears as too many branching vessels within the liver.

Pancreatitis

If visible changes are identified, the classic appearance of acute pancreatitis is an enlarged, hypoechoic pancreas having irregular margins and surrounded by hyperechoic mesentery. Only about 25% of cases of pancreatitis are icteric having increased likelihood of extrahepatic biliary obstruction and these tend to be the more sonographically severe cases.8,9 When pancreatitis is discovered, make special attempt to locate the duodenal papilla and bile duct to confirm suspicion of an extrahepatic biliary obstruction.

Conclusion

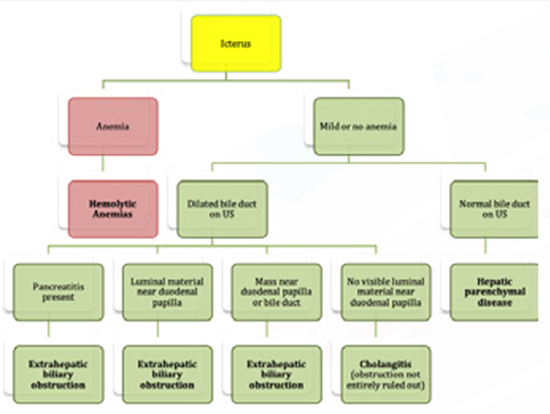

Follow the algorithm below for an approach to the icteric dog.

Figure 1. Approach to the icteric dog

References

1. Liptak JM, Dernell WS, Withrow SJ. Liver tumors in cats and dogs. Compendium. 2004;January:50–57.

2. Cuccovillo A, Lamb CR. Cellular features of sonographic target lesions of the liver and spleen in 21 dogs and a cat. Vet Radiol Ultrasound. 2002;43(3):275–278.

3. Bromel C, Barthez PY, Leveille R, Scrivani PV. Prevalence of gallbladder sludge in dogs as assessed by ultrasonography. Vet Radiol Ultrasound. 1998;39(3):206–210.

4. Crews LJ, Feeney DA, Jessen CR, Rose ND, Matise I. Clinical, ultrasonographic, and laboratory findings associated with gallbladder disease and rupture in dogs: 45 cases (1997–2007). J Am Vet Med Assoc. 2009;234(3):359–366.

5. Besso JG, Wrigley RH, Gliatto JM, Webster CRL. Ultrasonographic appearance and clinical findings in 14 dogs with gallbladder mucocele. Vet Radiol Ultrasound. 2000;41(3):261–271.

6. Nyland TG, Gillett NA. Sonographic evaluation of experimental bile-duct ligation in the dog. Vet Radiol Ultrasound 1982;23(6):252–260.

7. Zeman RK, Taylor KJ, Rosenfield AT, Schwartz A, Gold JA. Acute experimental biliary obstruction in the dog: sonographic findings and clinical implications. AJR Am J Roentgenol. 1981;136(5):965–967.

8. Hess RS, Saunders HM, Van Winkle TJ, Shofer FS, Washabau RJ. Clinical, clinicopathologic, radiographic, and ultrasonographic abnormalities in dogs with fatal acute pancreatitis: 70 cases (1986–1995). J Am Vet Med Assoc. 1998;213(5):665–670.

9. Kim HW, Oh YI, Choi JH, Kim DY, Youn HY. Use of laparoscopy for diagnosing experimentally induced acute pancreatitis in dogs. J Vet Sci. 2014;15(4):551–556.