Introduction

Epilepsy is a disease of the brain characterized by recurrent seizures originating from the brain. The signs of epilepsy are episodic, and epilepsy can become inactive for a period of time or even disappear. Seizure activity arises as a sequel to abnormal hyper synchronous electrical activity, which stems from a group of local cerebral neurons or from the whole cortex in collaboration with subcortical structures.

Epilepsy is characterized by a sudden loss of control and paroxysmal manifestations with seizures which suddenly occur and suddenly cease. Seizures are transient and seldom last longer than 2–3 minutes. Seizures typically follow a repetitive pattern where signs and sequence are identical from episode to episode in the individual animal. Signs may include motor-, sensory- and autonomic elements and behavioural disturbances. Consciousness may be altered or lost. In some individuals with epilepsy, seizures can be provoked by external factors such as, e.g., excitement, agitation, flashes of light, and sleep deprivation.

Factors involved in epileptogenesis may be: e.g., neuroplasticity/synaptic plasticity, decreased GABA (gamma amino butyric acid) activity, increased glutamate activity, new formation of excitatory circuits, receptor alterations, ion channelopathies, dysfunction of glia cells, cortical dysgenesis, and primary brain disease causing seizures such as inflammatory or neoplastic disease.

The prevalence of epilepsy in dogs in general has been estimated in an epidemiological study to be 0.76%. The prevalence of epilepsy in cats is believed to be lower, although no true epidemiological studies exist to document this. Several dog breeds are, however, associated with a much higher prevalence caused by an identified genetic or suspected genetic background for epilepsy. This leads to an unfortunate accumulation of epileptic individuals within such breeds. In the Lagotto Romagnolo a genetic background for epilepsy has been fully identified and in the Belgian shepherd partially identified. In other breeds, an accumulation of epileptic individuals with in families, have been documented by epidemiological studies (Labrador Retriever, Belgian Shepherd and Petit Basset Griffon Vendeen), or by pedigree studies (Keeshound, Labrador Retriever, Vizla, Shetland Sheepdog, Irish Wolfhound, English Springer Spaniel, Australian Shepherd and Border collie among others).

Classification of Epilepsy and Epileptic Seizures

The present presentation of epilepsy classification in veterinary medicine is based on the consensus statements which have recently been published by the International Veterinary Epilepsy Task Force (IVETF). This consensus statement group involves veterinary and human neurologists and neuroscientists, practitioners, neuropharmacologists and neuropathologists.

Classification of Epilepsy

Epilepsy is classified into categories based on known or presumed aetiology. Structural epilepsy (former known as symptomatic epilepsy) refers to epilepsy caused by a known/identified disorder of the CNS (cerebral pathology identified with e.g., CT, MRI or CSF examination). The term suspected structural epilepsy is used if brain pathology is strongly suspected (based on anamnestic information or abnormal findings on the neurological examination or both, signaling a focal brain lesion), but has not been confirmed. Idiopathic epilepsy refers to epilepsy where no structural cerebral pathology is identified, and where an identified or suspected genetic component is involved in the aetiology. Finally, a number of epilepsies are of unexplained origin (epilepsy of unexplained origin). In these cases, the epileptic seizures are however the only sign of disease. There is nothing in the history and no findings on clinical and neurological examination indicating intracranial pathology, and there are no abnormalities on specialized neuro-diagnostic tests (CT, MRI and CSF) suggesting intracranial pathology.

Note that epilepsy classification is continuously under revision and will be changed as our understanding of epilepsy aetiology in animals expand.

Classification of Epileptic Seizures

The clinical manifestation of epileptic seizures is directly related to the amount and distribution of abnormal electrical activity in the brain. Epileptic seizures are classified as generalized epileptic seizures, focal epileptic seizures (previously termed partial seizures) and focal seizures which evolve into generalized epileptic seizures.

With generalized epileptic seizures, there is a sudden outburst of abnormal electrical activity throughout both cerebral hemispheres. Without warning, the patient collapses with tonic, clonic, or tonic-clonic seizures. With focal epileptic seizures, the abnormal electrical activity arises in a localized group of neurons (the epileptic focus). The clinical signs reflect the functions of the area or areas involved. In dogs’, focal epileptic motor, sensory, autonomic or behavioural signs can manifest alone or in combination. Focal motor signs may include rhythmic jerks of an extremity, repeated jerking head movements, abnormal rhythmic blinking and twitching of facial musculature. Focal seizure activity believed to represent psychic and/or sensory epileptic seizure phenomena in the brain may in dogs result in a short lasting episodic change in behaviour such as, e.g., anxiousness, restlessness and abnormal clinging to the owner. Focal epileptic seizures including parasympatic/epigastric components may present as hyper salivation, vomiting and dilated pupils. Dogs are as a rule unconscious when having a generalized tonic-clonic epileptic seizure. For focal epileptic seizures, it is difficult to appraise different states of consciousness as this is limited to subjective interpretation made by the person observing the dog.

If the electrical activity in the epileptic focus becomes sufficiently massive, seizure activity can spread through subcortical structures to involve more areas and eventually the entire brain, a focal seizure evolving to become generalized. In that case the initial localized seizure signs will be followed by tonic- clonic convulsions. This is the most common seizure type observed in the dog. The onset of the focal epileptic seizure is often very short (few seconds to minutes) and the secondary generalization with convulsions follows rapidly. The focal onset may be difficult to detect due to its brief nature.

Seizure Phases

The epileptic seizure is organized in phases: an ictal phase characterized by seizure activity (focal seizure activity alone, generalized seizure activity alone, or focal seizure activity evolving into generalized seizure activity manifested by convulsions) which is followed by a postictal phase. In the postictal phase, the brain restores its normal function. The postictal phase may be very short, or last for several hours to days where the animal may be disoriented, ataxic, hungry or thirsty, express a need to go in the garden or appear exhausted. Postictal blindness or aggression may also be present.

In a few dogs, the ictal phase may be preceded by a so-called prodrome, a long-term change in disposition and indicator of forthcoming seizures. Humans with prodrome may experience days of, e.g., irritability, withdrawal or other emotional aberrations. In dogs the most common prodromal signs described are restlessness and attention-seeking which is known to the owner as a long term marker of a forthcoming seizure episode.

Treatment

The question of when to initiate treatment in animals with epilepsy is not an easy one. Overall, this decision is mainly influenced by seizure frequency, seizure density, severity of seizures and the owners’ opinion (as some owners are very eager to start treatment whereas others are more reluctant to do so). It is recommended by the IVETF and the ACVIM to start treatment if the animal experience >2 seizures in 6 month, experience status epilepticus or cluster seizures or experience severe (e.g., aggression) or long lasting post ictal signs.

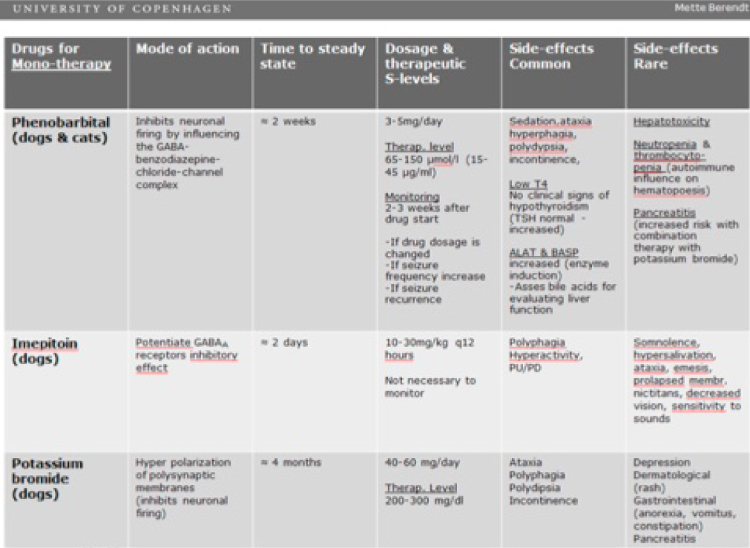

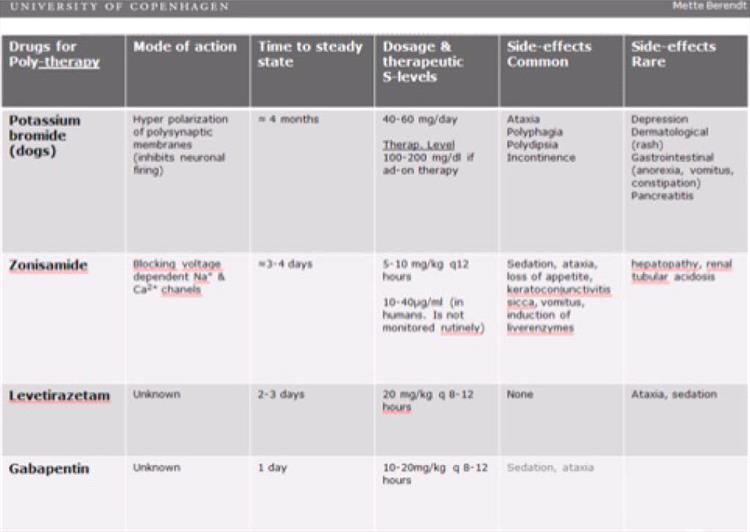

A list of drugs which can be used for treatment of epilepsy in dogs and cats appear from Table 1.

Table 1. Drugs used for treatment of epilepsy in dogs and cats

References

1. Heske L, Nǿdtvedt A, Hultin Jaderlund K, Berendt M, Egenvall A. A cohort study of epilepsy among 665.000 insured dogs: incidence, mortality and survival after diagnosis. The Vet J. 2014:202;471–476.

2. Hulsmeyer VI, Ascher A, Mandigers PJ, DeRisio L, Berendt M, Rusbridge C, Bhatti SF,Pakozdy A, Patterson EE, Platt S, Packer RM, Volk HA. International Veterinary Epilepsy Task Force’s current understanding of idiopathic epilepsy of genetic or suspected genetic origin in purebred dogs. BMC Vet Res. 2015;11:175. doi:10.1186/s12917-015-0463-0.

3. Berendt M, Farquhar RG, Mandigers PJ, Pakozdy A, Bhatti SF, De Risio L, Fischer A, Long S, Matiasek K, Mutiana K, Patterson EE, Penderis J, Platt S, Podell M, Potschka H, Pumarola MB, Rusbridge C, Stein VM, Tipold A, Volk HA. International Veterinary Epilepsy Task Force consensus report on epilepsy definition, classification and terminology in companion animals. BMC Vet Res. 2015;11:182. doi: 10.1186/s12917-015-0461-2.

4. Fredsǿ N, Toft N, Sabers A, Berendt M. A prospective observational longitudinal study of new-onset seizures and newly diagnosed epilepsy in dogs. BMC Vet Res. 2017;16:13(1):54. doi: 10.1186/s12917-017-0966-y.

5. De Risio L, Bhatti,S Munana K, Penderis J , Stein V, Tipold A, Berendt M, Farqhuar R, Ascher A, Long S, Mandigers PJ, Matiasek K, Packer RM, Pakozdy A, Patterson N, Platt S, Pooell M, Potschka H, Batlle MP. Rusbridge C, Volk HA. International Veterinary Epilepsy Task Force consensus proposal: diagnostic approach to epilepsy in dogs. BMC Vet Res. 2015;11:148. doi: 10.1186/s12917-015-0462-1.

6. Rusbridge C, Long S, Jovanovik J, Milne M, Berendt M, Bhatti SF, De Risio L, Farqhuar RG, Fischer A, Matiasek K, Munana K, Patterson EE, Pakozdy A, Penderis J, Platt S, Podell M, Potschka H, Stein VM, Tipold A, Volk HA. International Veterinary Epilepsy Task Force recommendations for a veterinary epilepsy-specific MRI protocol. BMC Vet Res. 2015;11:194. doi: 10.1186/s12917-015-0466-x.

7. BhaNi SF, De Risio L, Munana K, Penderis J, Stein VM, Tipold A, Berendt M, Farquhar RG, Ascher A, Long s , Loscher W, Mandigers PJ, Maliasek K, Pakozdy A, Patterson EE, Platt S, Podell M, Potschka H, Rusbridge C, Volk HA. International Veterinary Epilepsy Task Force consensus proposal: medical treatment of canine epilepsy in Europe. BMC Vet Res. 2015;11:176. doi: 10.1186/s12917-015-0464-z.

8. Podell M, Volk HA, Berendt M, Löscher W, Munana K, Patterson EE, Platt SR. 2015 ACVIM Small Animal Consensus Statement on Seizure Management in Dogs. J Vet Intern Med. 2016;30:477-490. doi: 10.1111/jvim.13841.

9. Potschka H, Ascher A, Löscher W, Patterson N, Bhatti S, Berendt M, De Risio L, Farquhar R, Long S, Mandigers P, Matiasek K, Mutiana K, Pakozdy A, Penderis J, Platt S, Podell M, Rusbridge C, Stein V, Tipold A, Volk HA. International Veterinary Epilepsy Task Force consensus proposal: outcome of therapeutic interventions in canineand fehne epilepsy. BMC Vet Res. 2015;11:177. doi: 10.1186/s12917-015-0465-y.