Rebecca L. Stepien, DVM, MS, DACVIM(Cardiology)

School of Veterinary Medicine, Department of Medical Science, University of Wisconsin, Madison

Madison, WI, USA

The Patient--Arrhythmia Interactions

In emergency patients, cardiovascular pathology, systemic illness and clinical situations interact to cause or aggravate arrhythmias. The best 'therapy' for most arrhythmias is to eliminate the underlying cause. Chronic heart disease patients have more risk factors for arrhythmia development than other patients. Systemic derangements are common in chronic heart failure patients due to direct drug effects or side effects of cardiovascular mediations.

Choice of Antiarrhythmic Therapy

Some characteristics of arrhythmias (e.g., heart rate (HR), origin of ectopic complexes) lead the clinician to choose a specific medication. Other characteristics (e.g., effect on cardiac output, probability of sudden death) help the clinician to decide if an arrhythmia is life-threatening (i.e., should be treated immediately, complete resolution is needed to avert death), symptom aggravating (i.e., may cause clinical signs complicating other diseases, control but not complete resolution may be sufficient) or clinically unimportant (i.e., requires only monitoring). Emergency arrhythmias can be treated indirectly (therapy or resolution of contributory clinical situation), directly with medical (drug) or mechanical (e.g., electrical conversion) therapy or with palliative methods that control the clinical signs without attempting to address the origin of the arrhythmia directly (e.g., pacemaker implantation).

Therapy of Bradycardic Arrhythmias

Sinus Bradycardia

Sinus bradycardias are heart rhythms that occur at a rate slower than the normal rate and have P waves for every QRS complex and narrow QRS complexes.

Sinus bradycardias are frequently associated with physical causes including use of sedatives or anaesthetic agents, anti-arrhythmic medications (e.g., beta-blockers) or medications or conditions that alter electrolyte balance or intensify vagal tone.

These sinus bradycardias are usually not associated with overt clinical signs of low cardiac output and resolve with removal of the underlying cause. If sinus bradycardia is associated with clinical signs of weakness or hypotension, HR can be supported with medications (e.g., anticholinergics) until diagnostics can be pursued. If the clinical importance of a bradycardic rhythm is in doubt, an atropine response test may be helpful. A baseline electrocardiogram (ECG) is recorded, 0.04 mg/kg of atropine is given intramuscularly and a follow-up ECG recorded 30 minutes later. A normal response includes a HR increase of >50% with normal conduction and indicates normal sinus node function.

Sinus Arrest, Bradycardia/Tachycardia Syndromes Associated with Sick Sinus Syndrome

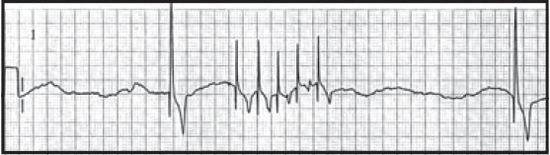

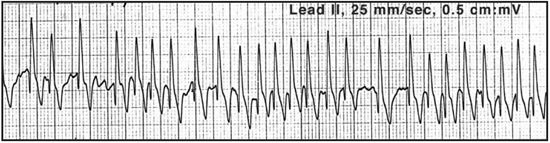

A sinus rhythm (upright P waves) with periods of sinus arrest terminated by escape complexes (narrow or wide QRS based on origin). In dogs, sinus rhythm with periods of sinus arrest and intermittent supraventricular tachycardia associated with clinical signs of syncope may represent sick sinus syndrome (Figure 1).

| Figure 1. Sick sinus syndrome. |

|

|

| |

Episodes of sinus arrest seldom lead to sudden death, but frequency of events may severely affect quality of life. Short-term therapy is the same as that for sinus bradycardia, but immediate pacing may be required if the rhythm is unresponsive to anticholinergics or if the animal is severely symptomatic. Sinus arrest and bradycardia/ tachycardia syndromes are most effectively treated with pacemaker implantation.

Atrial Standstill (Atrial Asystole)

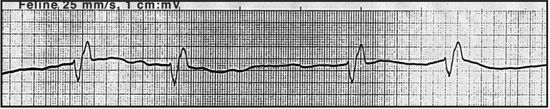

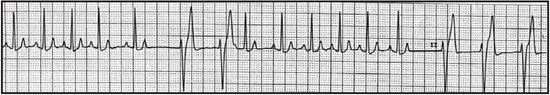

There is no atrial electrical activity (no P waves) with a junctional or ventricular escape rhythm (Figure 2).

| Figure 2. Atrial standstill. |

|

|

| |

Atrial standstill (asystole) may be associated primary disease of the atrial muscle or, more commonly, occurs secondary to severe hyperkalaemia. Atrial standstill due to atrial myopathy is treated with pacemaker implantation if the rhythm is bradycardic. Hyperkalaemia at a concentration high enough to lead to atrial standstill (usually > 8.5 mmol/l) is an emergency. Immediate therapy includes anticholinergics, intravenous saline and intravenous calcium administration along with definitive therapy to reduce potassium concentrations.

Atrioventricular Blocks

First-degree atrioventricular blocks (AVB): sinus rhythm, prolonged P-Q interval. Little haemodynamic significance.

First-degree atrioventricular blocks (AVB): sinus rhythm, prolonged P-Q interval. Little haemodynamic significance.

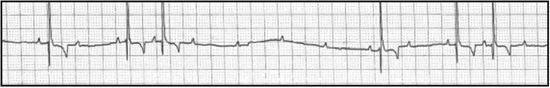

Second-degree AVB: sinus rhythm, some P waves are not associated with QRS complexes (Figure 3). Long periods of P waves without QRS complexes may lead to syncope.

Second-degree AVB: sinus rhythm, some P waves are not associated with QRS complexes (Figure 3). Long periods of P waves without QRS complexes may lead to syncope.

Third-degree AVB: P waves and QRS complexes present but unrelated to each other. Typically very bradycardic in dogs, moderately bradycardic in cats.

Third-degree AVB: P waves and QRS complexes present but unrelated to each other. Typically very bradycardic in dogs, moderately bradycardic in cats.

The most common cause of first-or second-degree AVB is high vagal tone or use of vagomimetic drugs (e.g., digoxin). In these cases, the underlying cause should be treated, rather than the AVB. If second-degree AVB is symptomatic and does not respond to anticholinergics, pacing is required. Third-degree AVB usually reflects primary nodal disease and anticholinergics are typically ineffective. Immediate therapy is warranted in dogs because third-degree AVB can lead to sudden death if the escape focus fails.

| Figure 3. Second-degree AVB. |

|

|

| |

Therapy of Tachyarrhythmias

Supraventricular (narrow complex) arrhythmias tend to carry a low risk of sudden death but the risk of clinical signs is high, especially with very high HR. Ventricular (wide complex) arrhythmias carry a variable risk of sudden death and the clinical signs seen are likewise variable, often depending on the HR. If the diagnosis is in doubt, consider faxing the ECG to a specialist for help with the diagnosis and advice on therapy.

Supraventricular Tachyarrhythmias (Typically Narrow QRS Complexes)

Sinus tachycardia: P waves are present and associated with narrow QRS complexes; HR <~240 bpm (dog) or ~260 bpm (cat). Sinus tachycardia is usually the result of clinical derangements and not related to primary cardiac disease unless heart failure is present. The underlying situation commonly involves hypotension, but pain may also contribute. Sinus tachycardia is not a fatal arrhythmia and usually resolves without direct therapy.

Sinus tachycardia: P waves are present and associated with narrow QRS complexes; HR <~240 bpm (dog) or ~260 bpm (cat). Sinus tachycardia is usually the result of clinical derangements and not related to primary cardiac disease unless heart failure is present. The underlying situation commonly involves hypotension, but pain may also contribute. Sinus tachycardia is not a fatal arrhythmia and usually resolves without direct therapy.

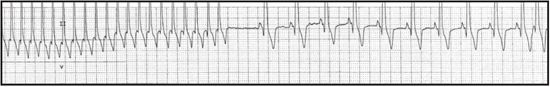

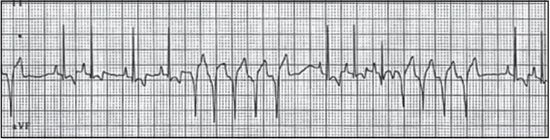

Atrial premature complexes, atrial tachycardia (AT), supraventricular tachycardia (SVT): narrow QRS complexes with or without P waves, arriving early (premature) or at high HR (>~240 bpm in dogs, ~260 bpm in cats) (Figure 4).

Atrial premature complexes, atrial tachycardia (AT), supraventricular tachycardia (SVT): narrow QRS complexes with or without P waves, arriving early (premature) or at high HR (>~240 bpm in dogs, ~260 bpm in cats) (Figure 4).

| Figure 4. Supraventricular tachycardia. |

|

|

| |

Single atrial ectopic depolarisations (APCs) may not require therapy if they occur at low frequency and no evidence of congestive heart failure (CHF) or known structural heart disease is present. SVT or AT often occurs at extremely rapid HR (~400 bpm in dog) and may severely decrease cardiac output. The first choice in medical therapy of AT or SVT is intravenous beta-blockers (BB), e.g., esmolol or propranolol, or calcium channel blockers (CCB), e.g., diltiazem. These medications may be given orally if no intravenous access is available, but BB should be avoided if signs of CHF are present.

Single atrial ectopic depolarisations (APCs) may not require therapy if they occur at low frequency and no evidence of congestive heart failure (CHF) or known structural heart disease is present. SVT or AT often occurs at extremely rapid HR (~400 bpm in dog) and may severely decrease cardiac output. The first choice in medical therapy of AT or SVT is intravenous beta-blockers (BB), e.g., esmolol or propranolol, or calcium channel blockers (CCB), e.g., diltiazem. These medications may be given orally if no intravenous access is available, but BB should be avoided if signs of CHF are present.

Atrial fibrillation (AF): rapid and irregular rhythm, narrow QRS complexes without P waves present (Figure 5). Spontaneous AF is usually associated with significant heart disease. A new diagnosis of AF may be the cause of sudden decompensation in a previously stable CHF patient. The therapeutic goal is to control the ventricular response in AF to ~140-160 bpm (dogs) or ~160-180 bpm (cats). Acute decreases in HR are recommended if ventricular rate is >220 bpm (dogs) or >240 bpm (cats). The most rapid and effective therapy presently used is intravenous diltiazem. Oral diltiazem or BB can be used if intravenous access is not available. BB may lead to acute worsening of CHF and should be use with caution in patients without CHF and should not be used when overt CHF is present.

Atrial fibrillation (AF): rapid and irregular rhythm, narrow QRS complexes without P waves present (Figure 5). Spontaneous AF is usually associated with significant heart disease. A new diagnosis of AF may be the cause of sudden decompensation in a previously stable CHF patient. The therapeutic goal is to control the ventricular response in AF to ~140-160 bpm (dogs) or ~160-180 bpm (cats). Acute decreases in HR are recommended if ventricular rate is >220 bpm (dogs) or >240 bpm (cats). The most rapid and effective therapy presently used is intravenous diltiazem. Oral diltiazem or BB can be used if intravenous access is not available. BB may lead to acute worsening of CHF and should be use with caution in patients without CHF and should not be used when overt CHF is present.

| Figure 5. Atrial fibrillation. |

|

|

| |

Ventricular Arrhythmias (Wide QRS Complexes without P Waves)

In ventricular arrhythmias, QRS complexes are wide and bizarre in contour and are not associated with P waves. Rapid, repetitive ventricular ectopy (ventricular tachycardia, VT) is more likely to cause clinical signs or sudden death than slower repetitive ventricular rhythms.

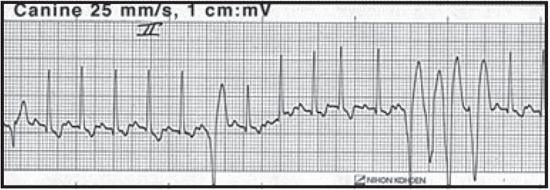

Accelerated idioventricular rhythms (AIR): ventricular rhythm, HR <160 bpm, depolarisation rate similar to sinus rate, first ectopic is late in diastole (Figure 6). These are frequently seen as a complication of severe systemic illness and are usually not associated with evidence of impaired cardiac performance, so therapy is aimed at rectifying the underlying problem. Hydration, oxygenation, electrolyte and acid-base abnormalities and pain should be assessed and managed appropriately. No direct anti-arrhythmic therapy is indicated if all of the following criteria apply: HR and blood pressure are within normal ranges and stable, no clinical signs of hypotension are apparent and no other ventricular ectopics interrupt AIR. Direct anti-arrhythmic therapy (as for VT) may be indicated if any of the following occur: HR >160 bpm, hypotension is present, premature ventricular ectopics or clinical signs of poor cardiac output present (e.g., weakness, syncope).

Accelerated idioventricular rhythms (AIR): ventricular rhythm, HR <160 bpm, depolarisation rate similar to sinus rate, first ectopic is late in diastole (Figure 6). These are frequently seen as a complication of severe systemic illness and are usually not associated with evidence of impaired cardiac performance, so therapy is aimed at rectifying the underlying problem. Hydration, oxygenation, electrolyte and acid-base abnormalities and pain should be assessed and managed appropriately. No direct anti-arrhythmic therapy is indicated if all of the following criteria apply: HR and blood pressure are within normal ranges and stable, no clinical signs of hypotension are apparent and no other ventricular ectopics interrupt AIR. Direct anti-arrhythmic therapy (as for VT) may be indicated if any of the following occur: HR >160 bpm, hypotension is present, premature ventricular ectopics or clinical signs of poor cardiac output present (e.g., weakness, syncope).

| Figure 6. Accelerated idioventricular rhythm (dog). |

|

|

| |

Ventricular premature complexes (VPCs) or ventricular tachycardia (VT) (Figure 7). If cardiac output is compromised OR electrical instability is suspected, therapy of any ventricular arrhythmia (VPCs or VT) is warranted. Ventricular arrhythmias significantly decrease cardiac output if severe myocardial dysfunction or heart failure is present or if the arrhythmia is highly repetitive or provides large proportion of total HR. Ventricular arrhythmias may be electrically unstable (and lead to sudden death) if the VT is at HR >~280 bpm or VPCs occur so prematurely that they 'land' on the previous complex's T wave (Figure 8). The cornerstone of acute therapy of ventricular arrhythmias remains intravenous lidocaine. If lidocaine is unsuccessful or contraindicated, intravenous procainamide or a BB may be used. If lidocaine is administered as a bolus and is effective, a continuous rate infusion (CRI) should be started immediately. When the patient is stable and can tolerate oral medications (e.g., sotalol, amiodarone, mexiletine), oral medications can be started while the CRI is still running and the CRI slowly discontinued. In cats, lidocaine can be used but at a much lower dose than in dogs. Intravenous or oral BB may be a better choice in cats that are not critically unstable.

Ventricular premature complexes (VPCs) or ventricular tachycardia (VT) (Figure 7). If cardiac output is compromised OR electrical instability is suspected, therapy of any ventricular arrhythmia (VPCs or VT) is warranted. Ventricular arrhythmias significantly decrease cardiac output if severe myocardial dysfunction or heart failure is present or if the arrhythmia is highly repetitive or provides large proportion of total HR. Ventricular arrhythmias may be electrically unstable (and lead to sudden death) if the VT is at HR >~280 bpm or VPCs occur so prematurely that they 'land' on the previous complex's T wave (Figure 8). The cornerstone of acute therapy of ventricular arrhythmias remains intravenous lidocaine. If lidocaine is unsuccessful or contraindicated, intravenous procainamide or a BB may be used. If lidocaine is administered as a bolus and is effective, a continuous rate infusion (CRI) should be started immediately. When the patient is stable and can tolerate oral medications (e.g., sotalol, amiodarone, mexiletine), oral medications can be started while the CRI is still running and the CRI slowly discontinued. In cats, lidocaine can be used but at a much lower dose than in dogs. Intravenous or oral BB may be a better choice in cats that are not critically unstable.

| Figure 7. Paroxysmal ventricular tachycardia (dog). |

|

|

| |

| Figure 8. Four closely coupled ventricular complexes, indicating an electrically unstable rhythm. |

|

|

| |

References

1. Stepien R, Boswood A. Cardiovascular emergencies. In: King, LG; Boag, A. eds. BSAVA manual of canine and feline emergency and critical care (second edition). Quedgeley, Gloucester: British Small Animal Veterinary Association, 2007; 57-84.