|

|

|

|

Veterinary Extenders

Thomas E. Catanzaro, DVM, MHA, FACHEDiplomate, American College of Healthcare Executives

"Veterinarians produce the gross; the staff produces the net!"

Dr. Tom Cat

A veterinary extender is someone or something who allows the primary provider (the veterinarian) a greater amount of time to see patients and to talk to clients. Sometimes the veterinary extender provides ancillary services such as nutritional or behavior counseling. At other times they relieve the veterinarian of business work, like inventory control or supervision of the animal caretaker team. In the final assessment, the veterinary extender may be a well-designed form, a very friendly computer program, or sometimes, a volunteer or dedicated staff member.

For contemporary veterinary nurses, animal caretakers, and receptionists (client relation specialists), this veterinary extender model is offered as the essence of shared practice success. The focus of this system of care giving is simply skilled veterinary healthcare professionals working in the best interest of the patient. For example, technicians once checked the patient into the facility, performed the bathing, and then discharged the patient to a pleased client. Now the client relations specialists screen the client, the outpatient nurse admits the case, while the animal caretaker (kennel person) does the bath. 23% of clients are referred to the inpatient nurse for a wellness screen since something is seen as "not right" by the bather; discharges are done by appointment with an inpatient or outpatient nurse. The modern outpatient nurse has assumed the supplemental role (veterinary extender) in client education, health screening (physical examination) of the patient at admission, and supplemental and targeted client education during the discharge from the healthcare episode.

An analogy to this veterinary extender care-giver model is based on the sandbox theory. Typically, children play alone in their sand boxes. In this model, however, all the kids in the neighborhood come to play in one giant sandbox and together they create a unique and special sand castle. If someone tries to knock the sand castle over or if it starts to rain, the kids in the sandbox rally to shore it up and make it even stronger. This is the secret to an effective practice team. Each person assumes they can make a difference in the quality care of the patient, client, and community.

THE MODEL

The veterinary extender care-giver model brings together professionals with diverse skills, talents, and abilities. Together they address issues at the very essence of veterinary medical practice: "How can we do more for the community we serve? How can we share and exchange our talents, knowledge, and skills to help our patients, support the veterinarian(s), but most important, assist our clients in their stewardship concerns toward our patients?"

Many practice owners fail to understand that the central issue for their staff is not often compensation and benefits, but rather client concern, patient care, and their environment. Practice staffs are justifiably angry at the profession because many veterinarians prevent them from practicing the profession for which they were educated and trained. Practice owners must realize that their staffs are no different from other professionals. If their needs go unmet, they will regress. Stymied in their search for self-actualization, they will look for self-esteem. If self-esteem is elusive, they will seek autonomy. With no autonomy, they will meet social needs through negative communications with co-workers. And if the social structure breaks down, they will pursue the basics of living: wages, salary, and benefits. In the process they may get what they want, but they will lose sight of why they initially entered veterinary healthcare; to care for the patients and support the clients. This is often the cause for "burn-out." The following interrelationships need to be understood to have a successful practice:

|

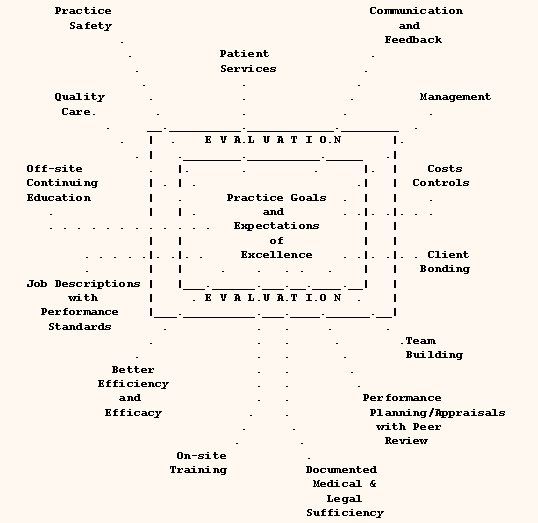

FIGURE 1: VETERINARY PRACTICE CARE-GIVER MODEL

Although every veterinary practice may not be willing to create the equivalent of a full veterinary extender care-giver model, each could benefit through increased participation and involvement of their staff members. In facilitating any innovation, keep in mind the following factors:

1. Prepare for a mixed reaction.

Some staff members may not enjoy an expanded role with its increased accountability and responsibility. Change is not comfortable, in fact, change requires discomfort to be established. But not with the practice or life, only with specific habits that have outgrown the practice benefit. Although some staff members are dynamos, others may just want to work eight hours and go home. Change is "too much effort" for the latter group. Realize that although some staff may want to stay with your practice forever, others will invariably leave.

2. Work on your own attitude and the example you set in daily activities.

Banish negative stereotypes. All too often supervisors or veterinarians make comments like, "What do they know? They're only receptionists . . ." or "Technicians just want to be junior veterinarians . . . ." What most staff members really want is to be all they can be within the practice. Although many veterinary practices have yet to create an environment where that can happen, your practice could be among the first.

3. Practice owners must be willing to spend time with the staff and other veterinarians.

At least once a month, they should attend a community veterinary meeting. At least quarterly, the lead technician and receptionist should attend an appropriate CE experience outside the practice facility. Equally as often, supervisors and leaders should talk to each staff member about his/her concerns, professional, practice and personnel.

4. Be willing to invest time in what will probably become a three-year process.

Remember that traditional systems of veterinary practice have been around for decades. Changing habits is a slow incremental process where a specific policy or procedure is identified for change. It is first "defrosted" by making people dissatisfied with the action or outcome, then the actions are remolded into a new procedure, and finally, it is "re-frozen" into a new habit by repetition. To expect a 24-hour turn-around in policies, attitudes, or behavior is unrealistic. Have patience and be prepared for delays, postponements, and backsliding during the maturation of the revised practice approach.

5. Encourage a positive attitude toward failure.

Help each member of the staff understand that if a program or effort fails to meet expectations, they have still gained by the learning process. They can never be expected to stumble unless they try to move forward. They can still revitalize the practice by building on current strengths and positive attitudes. Allow people to verbalize their concerns in a non-threatening atmosphere.

6. Get employed veterinarians to buy into the program.

Talk to the veterinarians in terms of patient welfare, client bonding, and returns to the practice. Help them understand that a good veterinary extender allows them to have more patient hands-on time and thus, greater productivity. The increased productivity benefits will cause commitments to the program when shared.

7. Share information routinely - including key financial reports.

Information does not need to be the bottom-line of a financial report, but rather, it needs to be an extract of those things that each person could affect in daily operations. If the staff feels important and involved, they will look for ways to improve the systems they can affect. Good leaders look for these opportunities to share accountability. Decreased costs and increased services will enhance the practice's fiscal position.

8. Focus on quality of care.

The client is more than a customer, and the pet is more than just a patient. Quality care centers on client needs, patient wellness, and perceptions of satisfaction. Continuous quality improvement (CQI) is based on pride being promoted at the individual staff member's level of contribution and the outcome being the client's perception of quality care. You don't need to educate most staff members about quality patient care -- just give them an environment where they can practice patient advocacy and concerned client communications. The effective veterinary extender must be allowed to make changes within established guidelines for the benefit of the practice without having to ask permission. The top quality healthcare practice will attract and retain clients looking for top quality veterinary services for their pet.

APPLICATION OF THE MODEL

The first step in the application of the veterinary extender care-giver model (review the previous diagram) is to administer the attached "charge out test" to every staff member during your next staff meeting (veterinarians must also participate). It is to be completed by independent work within five minutes using the routine resources available in the practice. At the end of this article is a clinical challenge that you, as a caring veterinary extender, must be able to solve. Once the entire staff does the clinical exercise, discuss it in a staff meeting. If the information was not readily available, that supports the need for a better veterinary extender program in the practice. Lost income can be captured. Ask for the rationale of the charges, pro or con, then ask what the best level of care should be at your practice. Do not be surprised in the range is over $200 within the staff.

Another important application principle that cannot be forgotten is that when PRIDE goes into the healthcare delivery, then QUALITY is what comes out. Quality is a perception of the client, not an input into the process. CQI occurs when the practice leadership releases control of the process and sets clear expectations of outcomes. It is when the practice leadership assigns accountabilities rather than tasks. It occurs when they encourage change for the betterment of the practice, by every staff member, without telling the staff member, ". . . what used to be . . ." or ". . . we don't do it that way . . . ."

PRIDE AND QUALITY

Some practices have adopted "core values" instead of job descriptions, such as "PRIDE" or "I CARE," which represent:

|

P - patient |

I - the important person in the formula | |

|

R - respect |

C - client comes first | |

|

I - innovation |

A - action is what the client wants | |

|

D - dedication |

R - respect for self and others | |

|

E - excellence |

E - excellence is competency |

There are many variations of how to use veterinary extenders. Some practices require three staff per on-duty veterinarian while other practices have one staff member for two veterinarians. The latter case never allows the development of a veterinary extender approach to healthcare delivery. The bottom-line for veterinary extenders in the current evolving progressive practice is simply:

"If it is to be, it is up to me."

PRACTICAL EXERCISE

PLEASE CHARGE OUT THIS CASE IMMEDIATELY:

No doctor is in the hospital and you MUST give an invoice to this vacationing person who is leaving town. Her one-year-old, 25-pound, Beagle-mix was hit by a car four days ago and admitted immediately thereafter for stabilization and evaluation. Everything is now okay, except that the pet needed to have a major organ removed (right kidney) to lead a normal life. The vaccinations were current at admission and the in-house fecal was negative. The pet is on year-round heartworm preventative and the blood test (PCV, TP, BUN, and Difil test) conducted pre-surgery was negative. The surgery took about one hour and the dog is being discharged 48 hours after the surgery. Because we used isoflurane gas anesthesia, there was only a very slight anesthetic risk. The client is settling the account right now, and the doctor did not write up the travel sheet (circle sheet), so how much do you tell the client to pay to settle the total surgical and healthcare bill at this discharge?

$ _______________

IDEAS FOR STAFF LEVERAGING

• �Outpatient Nurse

"Let me help you when the doctor is done . . ."

• �High-Density Scheduling

Half way through treatment, "Do you have any questions?," courtesy call

• �Preferred Client after Annual Life Cycle Consultation

Outpatient nurse appointment option

• �Client Relations Specialists

Welcome to Our Practice courtesy call

• �Human-Animal Bond Coordinator

Pet Partners, school outreach, news releases

• �Recovered Pet Program

"Do you still have two dogs and a cat?" - or - "All pets need a pet!"

• �Recovered Client Program

"The doctor and I missed you and Spike this week, is everything okay?"

• �Nutritional Counselor

"We are ordering, do you want me to order a refill?" courtesy call

• �Parasite Prevention & Control Specialist

Advocate of strategic deworming (CDC)

• �Dental Hygiene Nurse Technician

Three week home care follow-up

• �Behavior Management Advisor

Starts with house training, then socialization and feeding habits

• �Surgical Nurse "day before" courtesy call

Surgical Nurse "out of anesthesia" courtesy call

• �Resort Manager

People Time vs. Play time

• �Patient Advocate Coordinator

Handouts, "Traveling with Your Pet" News Releases, Newsletters

|

|

Copyright ACVC