Abstract

The Przewalski horse (Equus prezwalskii) became extinct in the wild during the 1960s. The last

recorded sightings of Przewalski horses, also called takhi, in Mongolian, occurred in the Dzungarian Gobi in Southwest

Mongolia.8,10 Whether this area is representative of past takhi range land or was merely the last refuge for this

species prior to extinction in the wild has been debated and has resulted in a desert-steppe controversy.2,9

However, Mongolian Government-UNDP sponsored recommendations for the reintroduction of takhi suggested establishing multiple

sites with a primary free-ranging self-sustaining population in the Dzungari Basin of the greater Gobi Desert.7

Projects that in the past strongly defended steppe reintroduction have lately also suggested that multiple sites in

different habitats should be established.12 At the present, six different takhi reintroduction projects exist:

two in Mongolia at Hustain Nuruu12 and Tachin Tal,11 two in China at Jimsar and Gansu,11

one each in Kazakhstan and Ukraine.3,12 Only the two projects in Mongolia have successfully released horses to

the wild. It is questionable whether the Chinese projects will ever be able to release the horses to the wild considering

the socio-economic and geo-morphologic restraints imposed on the potential release sites.11 No information is

available to the authors at the present concerning the status of the last two projects.

The Tachin Tal Project was initiated by the German Christian Oswald Stiftung (COS) and the Mongolian

Society for the Conservation of rare animals (MSCRA) of the Ministry of Environment with the support of various

international sponsors. In 1999 the International Takhi Group (ITG) was established to continue and extend this project in

accordance with the IUCN reintroduction guidelines.

In 1992 the first group of zoo born takhi arrived at the Tachin Tal site (45.53.80 N, 93.65.22 E) at the

edge of the 12500-km2 Gobi-B Strictly Protected Area and International Biosphere Reserve. Subsequent transports

were carried out in 1993 and yearly between 1995 and 1999. A total of 59 horses have been transported to date. In 1997, the

first harem group was released from the adaptation enclosures. In 1999, the first foals were successfully raised in the

wild. At the present three harem groups and one bachelor group have been released (n = 31).

A discussion of the basic requirements and considerations of a reintroduction program greatly exceeds

the scope of this abstract and the reader is referred to the IUCN document on translocations5 and

Kleiman.6

Before selecting animals for the transport to Southwest Mongolia certain health criteria must be

fulfilled. These are demanded by the Mongolian veterinary health officials and the IUCN reintroduction specialist group. The

horses must not be a health risk for domestic livestock, for other equids (e.g., Kulan E. h. hemionus) and other

species in the reintroduction area. The potential danger to free-ranging Przewalski horses also exists following the first

releases in 1997.

After receiving a thorough clinical examination, all animals were placed in a 30-day pre-shipment

quarantine. The clinical examination took diseases or lesions described in Przewalski horses (e.g., cleft palate,

degenerative myelo-encephalopathy) into consideration. Additionally, all horses were bled prior to shipment and serologic

examinations were carried out for the following diseases: equine infectious anemia (lenti virus), equine arteritis (toga

virus), vesicular stomatitis (rhabdo virus), glanders (Pseudomonas mallei) and contagious equine metritis

(Taylorella equigenitalis). Bacteriologic examination for Trypanosoma equiperdum was carried out. As of 2000,

serologic screening will be expanded to include equine viral pneumonitis and abortion (equine herpes virus 1 and 4), equine

coital exanthema (equine herpes virus 3) and equine influenza. Vaccination will be expanded to include equine herpes virus

1+4 (Reosequinplus® Hoechst Roussel Vet, Vienna). It is important to note that a modified live virus vaccine (e.g.,

Prevaccinol® Centeon Pharma, Marburg) should not be used in reintroductions as these have the inherent risk of a virus

introduction.

The horses received two doses of a broad-spectrum anthelmintic (Ivomec-P®, Merck Sharpe &

Dohme, Haarlem) and were vaccinated against equine influenza and tetanus (Prevacun FT®, Hoechst Roussel Vet, Vienna).

Special attention must be given to the crate dimensions and specifications to ensure a safe trauma free

transport to the reintroduction site. Total transport time can reach 50 hr in some cases. Crates must be smooth on the

inside and cushioned with neoprene foam. The floor must be slip-proof even with urine present. The animals are provided with

water and hay during journey breaks. However, the uncontrolled provision of hay has proven detrimental. The horses tend to

shove the hay to the rear of the crate with their hooves and therefore create an uneven floor. One horse was lost as he

managed to turn onto his back during the transport. Similar problems have been encountered in other Przewalski horse

transports (Bouman pers.comm., Zimmermann pers. comm.).

To reduce the potential stress related to transport, several horses have been treated with the long

acting neuroleptic drug perphenazine enantate (Decentan® Depot, Merck, Darmstadt) prior to shipment. Perphenazine at

150 mg/horse will be used on all future shipments.

Veterinarians not only accompany the shipments to Mongolia, but also are on hand to provide help in

cases of shipment trauma and exhaustion. The long term veterinary care is provided on-site by Mongolian veterinarians

employed by the project. As of 1999 and the installation of a permanent research facility at the Tachin Tal site, they are

aided by European veterinarians in doctoral research programs. Two doctoral programs are presently underway to survey the

dynamics and influence of parasites in the equids of the release area and to investigate the reproductive biology and

possible influence of stress (defined by fecal cortisol metabolites) on the takhi.

Information gained from necropsies carried out on site in the past has been scant. This led to the

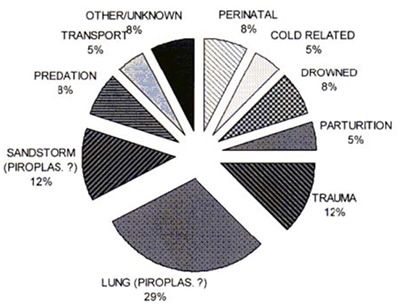

establishment of a basic necropsy protocol and adequate sample collection procedures. Analysis of the past deaths (Figure 1)

revealed that a total of 41% of the deaths had been attributed by local pathologists to "lung problems" and "effects of

sandstorm." Furthermore a significant increase in deaths was noted in the months April-May. In 1999 it was possible for the

first time to examine histopathologically formalin fixed samples (n = 4).

The prominent pathologic features in three animals were congestion of the lungs with pulmonary, alveolar

and interstitial edema accompanied by fibrin, erythrocytes (hemorrhage) and few macrophages and other inflammatory cells, a

highly congested spleen, the presence of hemosiderin-laden macrophages in different organs, and a moderate mixed cellular

infiltration in the portal fields in the liver. One animal showed severe renal lesions characterized by necrotizing

tubulonephrosis, multifocal interstitial hemorrhages, and presence of numerous protozoan organisms (Klossiella equi)

in the tubular epithelial cells. The pathologic lesions, especially the pulmonary edema, the generalized capillary

congestion and the highly congested spleen, the tubulonephrosis and the hemosiderin-laden macrophages in different organs

(indicative for hemolysis), associated with the clinical data, are suggestive, but not conclusive for an infection with

Babesia equi or B. caballi (piroplasmosis). An immunohistologic examination of the tissues for African horse

sickness (orbi virus) the most important differential diagnosis was negative. Other possible viral causes such as herpes or

influenza could not be definitely excluded at the time of print. The renal protozoan K. equi has been diagnosed in

two animals and is considered an incidental finding or opportunistic agent. The possible infection with Babesia has

been further reinforced through the serologic examination of three serum samples from the Tachin Tal. Two horses, which had

been in Mongolia in the spring prior to sampling, had positive antibody titers against B. caballi. The third horse,

which arrived in the summer months, was negative. These initial data indicate that the naive horses are potentially infected

with Babesia during their first spring in the Tachin Tal. At that time every year a massive infection with

Dermacentor nutalli ticks had been noted. A review of the literature revealed that the prevalence of equine

piroplasmosis in Mongolia and in neighboring northern China is extremely high.1,13 That piroplasmosis is

potentially an important mortality factor in combination with exertion and stress has been demonstrated in the

past.4 The influence of piroplasmosis as a pathogen and important mortality factor or co-factor will be

investigated in the coming months. Furthermore, acaricide treatment, and if necessary Imidocarb or Diminazene treatment,

will be implemented and monitored as of 2000. This example clearly demonstrates the importance of a thorough disease risk

assessment prior to shipment.

Anesthesia is an additional component of the veterinary care in Mongolia. It is necessary for

therapeutic sampling procedures and the placement of radio-collars for monitoring purposes. Standard Immobilon®

protocols have been adapted for procedures in Mongolia. A combination of etorphine, detomidine and butorphanol is presently

being used. This combination has the advantage of reducing the pacing phase during induction and therefore reducing the risk

of trauma. Veterinarians are presently also involved in all aspects of management and research in the Tachin Tal project.

This project has demonstrated that Przewalski horses can successfully be reintroduced into the

semi-desert environment of the Dzungarian Gobi in Mongolia. However, many procedures and methods are incomplete and have to

be improved in future years to ensure that a self-sustaining population can be established at this site. A

multi-institutional co-operative approach between biologists, botanists, veterinarians and other specialists from the

various projects will be necessary to fulfill the goal of returning this species to the wild in Mongolia.

| Figure 1. |

Przewalski horse (Equus prezwalskii) causes of death in Tachin Tal in the period 1992-1999. |

|

| |

Acknowledgments

The authors thank all staff and co-workers on site in Mongolia, members of the ITG in Europe

especially Christian Stauffer and all students past and present involved in the Project. Furthermore, we thank Dr. Peter

Wohlsein for performing the IHC for African horse sickness.

References

1. Avarzed A, DT De Waal, I Igarashi, ASaito, T Oyamada, Y Toyody, N Suzuki. 1997. Prevalence

of equine piroplasmosis in central Mongolia. Ond. J. Vet Res. 64: 141-145.

2. Bouman DT, JG.Bouman. 1994. The history of Przewalski's horse. In: L. Boyd, and D.A. Houpt

(eds.): Przewalski's Horse. The history and biology of an endangered species. State University of New York Press,

Albany. Pp. 5-38.

3. Duncan P. 1992. Zebras, asses and horses: an action plan for the conservation of wild

equids. World conservation Union/SSC Equid Specialist Group, Gland Switzerland.

4. Hailat NQ, SQ Lafi, AM Al-Darraji, FK Al-Ani. 1997. Equine babesiosis associated with

strenuous exercise: clinical and pathological studies in Jordan. J. Vet. Parasitol. 69: 1-8.

5. International Union for Conservation of Nature and Natural Resources (IUCN). 1987.

Translocations of living organisms: introductions, re-introductions and re-stocking. IUCN council position statement. Gland,

Switzerland.

6. Kleiman DG. Reintroduction programs. 1996. In: D.G. Kleiman, M.E. Allen, K.V. Thompson, and

S. Lumpkin (eds.): Wild Mammals in Captivity. Principles and Techniques. The University of Chicago Press, Chicago,

London. Pp. 297-305.

7. Mongolia Takhi Strategy and Plan Work Group. 1993. Recommendations for Mongolia

´takhi strategy and plan. Mongolian Government, Ministry of Nature and Environment, Ulaan Baatar.

8. Ryder OA. 1995. Genetical analysis of Przewalski horse in captivity. In:V.E. Sokolovand,

V.N. Orlov (eds.): The Przewalski Horse and its Restoration in Nature in Mongolia. Proc. of an FAO/UNEP Meeting,

Moscow, CMP GKNT. Pp. 50-103.

9. Ryder OA. 1993 Przewalski's horse: prospects for reintroduction into the wild. Cons.

Biol. 7:13-15.

10. Sokolov VE, G Amarsanaa, MW Paklina, MKPosdnjakowa, EI Ratschkowskaja, N Chotoluu. 1992. Das

letzte Przewalskipferd Areal und seine geobotanische Charakteristik. Proc. 5th. Intern. Symp. On the preservation of the

Przewalski Horse. Zoologischer Garten Leipzig, Leipzig, Germany.

11. Stauffer C, E Isenbügel. 1998. Die Wiederansiedlung des Przewalskipferdes in der Mongolei.

Infodienst Wildbiologie & Oekologie.

12. Van Dierendonck MC, MF Wallies de Vries. 1996. Ungulate reintroductions: experiences with the

takhi or Przewalski horse (Equus ferus przewalskii) in Mongolia. Cons. Biol. 10: 728-740.

13. Yin H, W Lu, J Luo. 1997. Babesiosis in China. Trop. Anim. Health Prod. 29: 11s-15s.