|

|

|

|

Management of Chronic Renal Failure: Beyond the Can

Melissa S. Wallace, DVM, Dipl. ACVIM

Overview

Characteristic of chronic renal failure (CRF) are: historical signs consistent with chronic renal disease (e.g. polyuria, polydipsia, weight loss, poor haircoat), anemia, small renal size and/or deranged renal architecture, polyuria and/or hypokalemia. The approach to management of chronic renal failure is usually more conservative than with ARF, except in cases of uremic crisis.

Any insult that causes significant damage to renal parenchyma can cause chronic renal failure. Once established, CRF is a naturally progressive disease, even if the inciting cause is removed. Many theories about why this is the case have been proposed and studied. One theory is that as there are less nephrons, the single nephron glomerular filtration rate increases, which causes intraglomerular hypertension and hyperfiltration. This in turn causes damage to the glomerulus by endothelial damage, activation of platelets, increased protein flux within the glomerulus and decreased permselectivity of the GBM. These changes result in sclerosis of the glomeruli and eventual glomerular death, followed by atrophy of the tubules and interstitial fibrosis. Other common pathways of response which may contribute to progression of CRF are; renal secondary hyperparathyroidism, systemic hypertension, renal ammoniagenesis, hypercoagulability, chronic hypokalemia, lipid disorders, and activation of inflammatory mediators within the kidney. The end stage changes seen on renal histopathology are similar regardless of the inciting cause of the renal failure.

Chronic renal failure cannot be cured; therefore the long-term prognosis is poor. However, many dogs and cats live quality lives with chronic renal failure for months to years with supportive care. Because of increased single nephron GFR in chronic renal failure, the relationship between total GFR and % nephron loss is not linear, and the animal can often compensate remarkably for advanced renal disease.

Diagnostic Approach to Chronic Renal Failure

|

Minimum Data Base |

Case Selective Database |

|

Serum biochemical profile |

Ultrasound |

|

Complete blood count |

Blood pressure |

|

Urinalysis |

Urine protein:creat. |

|

Urine culture (by cystocentesis if possible) |

IVP, scintigraphy |

|

Abdominal radiograph |

Renal biopsy |

Goals for Management of Chronic Renal Failure

1. Diagnose and treat the underlying cause if possible

2. Avoid factors that exacerbate CRF

3. Slow the natural progression of CRF

4. Manage the uremic syndrome

Therapeutic Approach to Chronic Renal Failure

1. Fluid Therapy

a. Which CRF patients need fluid therapy?

i. Decompensated patients who are dehydrated, anorectic, depressed, vomiting, etc. (i.e. uremia).

ii. Patients with a recent exacerbation of CRF or 'acute on chronic' renal failure.

iii. The history and physical examination are more important factors than the BUN and creatinine, unless there has been a recent and significant increase in azotemia.

b. How should the fluids be administered?

i. If the patient is dehydrated and decompensated, the intravenous route is the best, because fluid in excess of maintenance can be given. The diuresis may increase excretion of uremic toxins.

ii. If the patient has stable renal failure but is having trouble maintaining hydration due to polyuria, then subcutaneous fluids on an ongoing schedule are very helpful, especially in cats.

iii. If you can not give intravenous fluids slowly and continuously (i.e. 24- hour care facility), then you may cause more harm than good by making rapid changes in the animal's sodium and fluid load by giving IV fluids. Renal failure patients have lost homeostasis, and can not make rapid adjustments in salt and water balance. Bolus IV fluid therapy for renal failure is not an appropriate compromise to scheduling and staffing problems. Referral to a 24-hour care facility is ideal. If this is not possible, then subcutaneous fluids, or a combination of IV and subcutaneous fluids, may be better.

c. When and how should the fluid therapy be stopped?

i. Give IV fluids (i.e. diuresis) until the patient no longer shows any improvement in the BUN and creatinine on consecutive daily or every other day samples, assuming excellent hydration status. This is referred to as the patient's 'baseline creatinine'. There is no specific time limit for improvement.

ii. Once the patient's baseline creatinine has been reached, gradually taper the IV fluids over 1-2 days, rather than stopping the fluids abruptly. Abrupt cessation of high rates of IV fluid therapy in renal failure patients may result in subsequent dehydration and relapse of uremic signs.

iii. Some patients are changed from IV fluid diuresis to maintenance subcutaneous fluids rather than being taken off fluids. This depends on the degree of azotemia at the time of reaching baseline, and the patient's clinical status and history.

d. What kind of fluids should be administered?

i. Begin with an isotonic balanced electrolyte solution such as lactated Ringer's or acetated Ringer's solution. Another good choice is 0.9% saline, especially before the potassium status is known.

ii. For maintenance fluid therapy once the patient is rehydrated, you may continue with the same fluid, or switch to a lower sodium solution such as � strength LRS with 2.5% dextrose.

e. Rate of fluid administration:

i. Replace deficits (dehydration) over 24 hours using the formula;

% Dehydration x B.W. (kg) x 1000 = ml/day

ii. Add maintenance fluids at 50 - 60 ml/kg/day

iii. Add a 'push' for diuresis of 2.5 - 5 % of B.W. as fluid per day, if cardiac function and serum albumin are normal.

f. Potassium Supplementation:

i. Potassium is supplemented in CRF according to "Scott's sliding scale", because loss of potassium through diuresis and vomiting, decreased intake, and prior total body depletion often results in hypokalemia. Clinical signs are muscle weakness, depression, anorexia and ventral neck flexion (cats).

ii. Dosing guidelines ("Scott's Sliding Scale")

|

Serum [K+] |

|

KCl to add per Liter |

|

3.5 - 4.5 |

|

20 |

|

3.0 - 3.5 |

|

30 |

|

2.5 - 3.0 |

|

40 |

|

2.0 - 2.5 |

|

60 |

|

< 2.0 |

|

80 |

iii. KCl must be given as a slow infusion, preferably with an infusion pump, especially at high rates of supplementation. Do not exceed 0.5 - 1 mEq/kg/hour.

iv. Monitoring of serum potassium is performed every 24 - 48 hours during IV fluid diuresis, more often if there is a significant problem.

v. Oral supplementation is very effective. The usual supplement for hypokalemic animals is potassium gluconate at 1 - 3 mEq/kg/day divided BID - TID PO.

2. Dietary Therapy

a. Protein restriction - potential benefits include:

i. Decreases glomerular hyperfiltration, which may slow progression of glomerulosclerosis.

ii. Protein restricted diets are phosphorus restricted, which delays onset of renal secondary hyperparathyroidism and may slow progression of glomerulosclerosis.

iii. Moderate protein restriction reduces proteinuria in glomerulopathies.

iv. Protein restriction may reduce net acid load and renal ammoniagenesis, which may slow progression of CRF.

v. May reduce serum lipids.

vi. May reduce immune cell activity and intraglomerular coagulation within the kidney.

vii. Improves the symptoms of uremia - this is probably the most significant advantage!

b. Recommendations

i. Moderate protein restriction is recommended for all uremic patients, and may be beneficial in early CRF patients. Examples are Hill's K/D, Eukanuba Veterinary Diets Nutritional Kidney Formula Early Stage, or Purina Veterinary Diets N/F.

ii. Be cautious to avoid malnutrition by monitoring body weight, serum albumin, anemia, haircoat and BUN:creatinine ratio.

iii. For severe uremia or intractable hyperphosphatemia, there are diets with severe protein and phosphorus restriction (e.g. Hill's U/D or Eukanuba Nutritional Kidney Formula Advanced Stage).

iv. If a patient is not meeting his energy needs with food intake, he will catabolize body proteins for energy. This contributes to acidosis, renal ammoniagenesis, and uremia. Adequate 'bad' calories are better than inadequate 'good' calories!

c. Nutritional support "Beyond the Can"

i. Enteral nutrition is preferred for uremic patients if it is at all possible. This approach nourishes the gut as well as the body, reducing the risk of bacterial translocation and sepsis.

ii. Feeding tubes (PEG, esophagostomy, nasoesophageal) are very helpful in the medical management of CRF. Bigger tubes can be used for blenderized canned renal diets. Esophagostomy tubes are often preferred due to lack of specialized equipment, short anesthetic time required, and simplicity of placement and care.

iii. Patients with severe vomiting and/or hypoalbuminemia may benefit from PPN or TPN. Strict intravenous catheter care, nutritional knowledge, and critical care nursing support are essential for success with these therapies. A local human hospital pharmacy will sometimes prepare the prescribed solution for the veterinarian.

3. Management of Hypertension

a. Potential benefits of diagnosing and managing hypertension in CRF:

i. Systemic hypertension reaches the glomerulus, promoting glomerulosclerosis and proteinuria. Effective antihypertensive therapy may slow progression of glomerulosclerosis.

ii. Effective antihypertensive therapy may avoid disastrous outcomes (stroke, acute retinal hemorrhage, detachment and blindness).

b. Prevalence of hypertension in CRF is high

i. Dogs - 61%, Cats - 61 to 65%

ii. Dogs with GN - 80%

c. Blood pressure measurement techniques

i. Direct = gold standard.

ii. Oscillometric - not accurate for cats, useful for dogs, will miss some hypertensive patients. Cuff size and position is very important. Difficult to evaluate quality of the measurement.

iii. Doppler - best technique for cats, also works well in dogs, will miss some hypertensive patients. Cuff size and leg position is important, as is getting a strong and reliable signal. No mean or diastolic pressure is obtained.

d. Therapy

i Treat dogs and cats with a repeatable Doppler over 180 mm Hg and/or an oscillometric > 170 mm Hg (dogs).

ii. Therapeutic options in CRF

1. Salt restriction (usually not effective alone)

2. Calcium channel blockers

a. Amlodipine is currently the drug of choice

b. Dose for dogs is 0.125 - 0.25 mg/kg/day

c. Dose for cats is 0.625 - 1.25 mg/cat/day

3. ACE inhibitors (benazepril, enalopril)

a. Enalopril 0.25 - 0.5 mg/kg PO SID - BID

4. Alpha-blockers (prazosin)

5. Beta-blockers (atenolol, propranolol)

4. Anemia of Chronic Renal Failure

a. Pathogenesis involves reduced ability of kidneys to make erythropoietin, resulting in normocytic, normochromic, nonregenerative anemia.

b. Contributing factors include shortened RBC survival in the uremic environment, G.I. bleeding from uremic gastroenteritis, effects of uremia on the bone marrow, and protein/calorie malnutrition.

c. Therapy

i. Androgens

1. Not very effective and may take 2 - 3 months.

2. Injectables work the best.

3. Androgens are toxic in cats (stanazolol - just say no!).

ii. Recombinant erythropoietin

1. Human product causes high incidence of anti-erythropoietin antibodies.

2. The anemia is worse than before therapy, and may take months to resolve (i.e. this can be fatal).

3. Other potential side effects; seizures, polycythemia, hypertension, stroke.

4. Canine and feline recombinant erythropoietin is being investigated.

5. Protocol

a. 50 - 150 U/kg SQ three times weekly

b. Iron supplement; 100 - 300 mg/day (dog) and 50 - 100 mg/day (cat).

c. Taper frequency and dose to avoid polycythemia

d. Monitor PCV weekly

iii. Anti-ulcer medications (see Uremic Gastroenteritis)

iv. Blood transfusions may be helpful during a uremic crisis

5. Controlling Renal Secondary Hyperparathyroidism

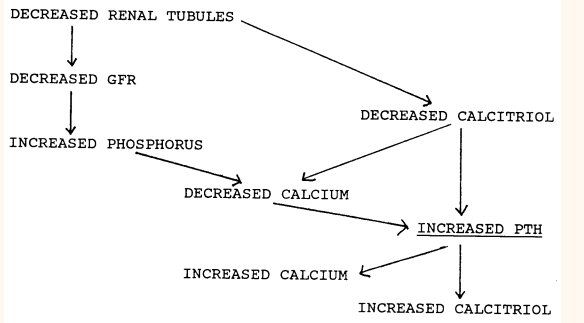

a. Pathophysiology (see diagram)

|

i. This system will normalize calcium and phosphorus, at the expense of elevated PTH and bone demineralization

ii. PTH is considered to be a uremic toxin, and it may contribute to progression of CRF through a variety of proposed mechanisms.

iii. As compensation eventually fails, the Ca++ x Phos product will exceed 55, and soft tissue mineralization (i.e. renal) will result, causing further nephron damage.

b. The Role of Diet and Phosphate Binding Agents in CRF

i. Control of hyperphosphatemia through dietary restriction of phosphorus is often effective at reducing hyperparathyroidism and signs of uremia.

ii. Phosphate binding agents are useful adjuncts to dietary therapy.

1. aluminum hydroxide 30 - 90 mg/kg/day divided, given at mealtimes

2. calcium acetate 60 - 90 mg/kg/day divided, with meals

3. calcium carbonate 90 - 150 mg/kg/day divided, with meals

iii. Monitor for hypercalcemia if using calcium-containing agents.

c. The Role of Calcitriol in Reducing PTH

i. Due to the above mechanisms, some nephrologists advocate replacement of calcitriol in patients with renal secondary hyperparathyroidism and normal serum phosphate levels.

ii. Proposed benefits of calcitriol therapy include;

1. Reduced PTH production and secretion

2. Regression of parathyroid gland hyperplasia

3. Reduction in PTH receptors within the kidney

4. Reduction in uremia +/- slower progression of CRF

iii. Protocol

1. 1.5 - 3.5 ng/kg/day PO SID

2. Monitor serum calcium, phosphorus, BUN and creatinine after one week, and then monthly (with PTH levels).

6. Management of Uremic Gastroenteritis

a. H-2 blocker therapy

i. Decreased GFR causes an accumulation of the hormone gastrin, promoting gastric hyperacidity. Other uremic toxins contribute to uremic gastrointestinal ulceration. Centrally-acting uremic toxins contribute to the nausea.

ii. Choices are cimetidine, ranitidine or famotidine. These drugs are renally excreted; the dose and/or frequency should be reduced in renal failure patients.

b. Cytoprotective drugs

i. Sucralfate is a cytoprotective drug for gastrointestinal ulceration, and is a phosphate-binding agent. It can interfere with absorption of other drugs.

ii. Misoprostil has cytoprotective effects, but may induce secretory diarrhea.

c. Anti-emetic therapy

i. Metoclopramide

1. Acts at the chemoreceptor trigger zone, and is therefore a rational therapy for uremic nausea.

2. Give 1 - 2 mg/kg/day IV as a CRI (protect from light) or give 0.2 - 0.4 mg/kg TID SQ, IM, PO

ii. Prochlorperazine

1. In severe cases, this is sometimes more effective than metoclopramide, but it has sedative and hypotensive effects. Start at a low dose and monitor for side effects. Dose = 0.1 - 0.5 mg/kg TID SQ, IM

NOBODY MADE A GREATER MISTAKE

�THAN HE WHO DID NOTHING

BECAUSE HE COULD ONLY DO A LITTLE

Edmund Burke

|

|

Copyright ACVC