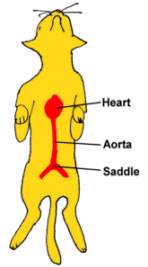

It stems from the heart itself, where it arches back and runs down the length of the back, ultimately splitting into the arteries supplying the back legs. The split where the aorta becomes the left and right iliac arteries is called the saddle. Illustration by MarVistaVet

(Also called saddle thrombus)

One tends to feel apprehensive about a condition with the acronym FATE, and rightly so. FATE (feline aortic thromboembolism) is a dramatic and painful condition with serious implications. It comes on suddenly and appears to paralyze the cat, causing one or both rear legs to become useless and even noticeably cold. The cat will hyperventilate and cry out with extreme pain. Despite the extreme presentation, the cat may be able to recover from the episode, but it is important to understand how this came to be in order to make decisions.

A thrombus is a large blood clot.

An embolism is a small blood clot lodged in an unfortunate location.

What is a Saddle Thrombus?

saddle thrombus radiograph

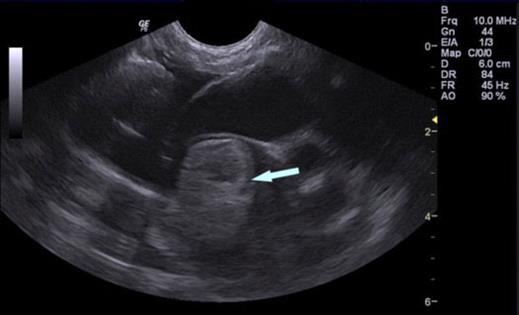

Arrow shows a large clot in the left atrium of a cat with a saddle thrombus. Image courtesy of Veterinary Specialists of the Valley and the North Hollywood Animal Care Center

A saddle thrombus is a blood clot that breaks off from a larger blood clot in the heart, travels down the aorta, and lodges at the saddle. Not only is the blood supply to one or both rear legs cut off but a metabolic cascade results, leading to the release of assorted inflammatory mediators (especially serotonin). The muscles of the rear legs become hard, the foot pads become bluish in color, and the condition is extremely painful. The inflammatory mediators readily lead to circulatory shock. The aorta is the largest artery in the body. It stems from the heart where it arches up and runs down the length of the back, ultimately splitting into the arteries supplying blood to the back legs. The split where the aorta becomes the left and right iliac arteries is called the saddle.

72 percent of cats with a saddle thrombus have both rear legs affected.

Where the Saddle Thrombus Came from

The saddle thrombus comes from a larger clot in the left atrium of the heart. This obviously begs the question as to why there would be a large blood clot in a cat’s heart. In fact, 89 percent of cats with a saddle thrombus have heart disease. Heart disease leads to turbulent blood flow, which encourages the formation of clots.

Not every cat with heart disease will form an abnormal clot, in fact, most will not; but there is presently no clear way to predict which cats will form these clots and which ones will not. That said, there are some suggestive echo findings that are felt to predict increased risk. In cats with hypertrophic cardiomyopathy, the most common form of feline heart disease, the size of the left atrium is one factor that is considered. The presence of “smoke” in the atrium during echocardiography is another factor. (“Smoke” is the whispy material seen in the circulating blood.) Both these factors are considered controversial but when they are seen, most cardiologists will recommend some kind of therapy to reduce clotting tendency (i.e., a blood thinner). The problem is that, in order to go on preventive therapy, there has to have been a reason to see a cardiologist in the first place (heart murmur during a physical exam, heart enlargement incidentally found on a radiograph, abnormal blood test, or actual symptoms of heart disease). The majority of cats with aortic thromboembolism have had none of these things, and the saddle thrombus is the very first symptom of a problem.

In 76% of cats with saddle thrombus, the FATE episode was the first sign of heart disease.

How Bad is this Situation?

The outcome is variable but has the potential to be very bad. Let's review the possibilities.

Best Case Scenario (Saddle Thrombus But No Concurrent Heart Failure)

Cats almost never have a FATE episode unless there is an underlying heart disease, so it is not unusual for the cat in question to also have heart failure; in fact, about half of them do. This, of course, means that about half of them don't. If there is only the thrombus and its associated pain to deal with, this makes the job simpler as the goal becomes pain control until the thrombus can dissolve and circulation can be restored.

That said, having a thrombus cutting off circulation to the legs can involve some very serious tissue damage and can be life-threatening in and of itself. A lot of toxic biochemicals are generated in the damaged tissue, and when the clot dissolves, these are all released into the rest of the circulation and this event can be lethal even without heart failure. The clot damage can be severe, symmetrical, and disastrous, or it can create only a partial circulatory blockage, and some improvement in function may be evident in a couple of days. Recovery of function can be complete or partial, and it may take several weeks to tell.

Basically, for the cat with a thrombus and no heart failure, the take-home points are:

- Treatment is largely about pain control and nursing care over the next couple of weeks.

- Even though heart failure is not present now, it is likely in the future, so appropriate medication (and evaluation by a veterinary cardiologist) is likely needed.

- Blood thinners (anti-coagulation) will be needed to help prevent future saddle thrombi.

- Even without heart failure, the cat may not survive the circulatory situation. There are parameters that can help determine this at the start (body temperature, heart rate, blood potassium level, blood pH).

- Full function may or may not recover.

Saddle Thrombus With Concurrent Heart Failure

In this scenario, the cat not only has the pain and paralysis of the saddle thrombus but is also in active heart failure. Even if the thrombus situation resolves relatively promptly with initial signs of limb function recovery and acceptable pain control after a couple of days, there is still a life-threatening cardiac crisis to contend with. The heart failure alone may be lethal in the short term, but let's assume the heart failure can be controlled quickly with medication AND the recovery from the thrombus is in progress. The cat will need heart medication, blood thinners, and nursing care while the rear legs recover. The median survival of saddle thrombus cats with heart failure is 77 days, while the median survival of saddle thrombus cats without heart failure is 223 days.

Tissue Damage from Thrombus

The good news is that permanent limb damage is the exception and not the rule, but it is possible. Some cats will lose skin or even muscle from the circulatory compromise. About 5% of cats will have tissue damage appearing as an open wound. As circulation returns, this sort of injury should heal. Another 5 percent will have more serious damage, and the occasional cat will require amputation of a limb.

Rapid Death from the Tissue Damage or Heart Failure

Many cats will die in the hospital. Some are simply overcome by heart failure. Some will throw another blood clot or multiple clots to a less survivable location, such as the brain or lung blood vessels. Some will suffer what is called a reperfusion injury when, as circulation returns to the limbs, toxic biochemicals from the limbs enter the main body of the circulation. Large amounts of potassium released from dying cells can be enough to fibrillate the already diseased heart. A saddle thrombus is a serious event. Is it likely to be lethal? It turns out the best predictive parameter is the body temperature at the time of presentation to the hospital. Cats with an initial body temperature over 98.9⁰F have a greater than 50 percent chance of avoiding this disaster and getting well enough to return home.

Euthanasia

Because of the potential for repeat saddle thrombus episodes, the need for regular medication administration at home, and the potential long-term treatment of heart disease, not to mention the seriousness & painfulness of the cat’s initial predicament, approximately 50-75% of pet owners elect euthanasia without attempting treatment.

Some Statistics

- 50 percent of treated cats survived to be discharged from the hospital.

- The median hospitalization time was two days.

- The median survival time of cats that used aspirin for future clot prevention was 192 days, while the median survival time of cats that used clopidrogrel bisulfate was 443 days.

- Of cats who used aspirin as their main clot prevention drug after discharge, 25% of them had at least one more FATE episode at some point (usually in 6-12 months)

- Cats that ultimately regain rear limb function are generally showing improvement within four days though it can take as long as a couple of weeks. The cat may require a great deal of nursing care until he/she is able to walk.

- Read more about the care of a pet with rear limb paralysis.

What to Expect at the Hospital

The doctor will need to quickly determine if the cat has a saddle thrombus or some other reason for rear limb paralysis and pain. The saddle thrombus patient will have cold rear feet, with a bluish or purplish color of the pads when compared to the front feet. Sometimes a toenail will be clipped short on a rear toe to check for bleeding. The diagnosis is often clinched by comparing a blood glucose level taken from the front of the body against one taken from the rear legs. Pain control is generally initiated while these preliminary evaluations are being performed. Obviously, the initial body temperature is recorded so as to assist in making a prognosis and assessing the severity of the situation.

Once the cat is more comfortable, more comprehensive blood testing can be performed and chest radiographs can be taken. In doing this, the cat is assessed for kidney toxins, toxins related to poor circulation, general biochemical body function, stress, heart failure, and possible lung cancer. If heart failure is present, diuretics will be needed to relieve extra fluid from the circulation and ease the burden on the weakened heart. There is controversy about using injectable blood thinners, but many hospitals will begin them and later transition to oral clopidogrel, aspirin or both.

Most cats will present to their regular veterinarian's office for initial care. The question will arise as to whether 24-hour care is needed or likely to be worth the extra expense, stress of travel to a specialty center, etc. The benefit of the specialty center includes the ability to continue pain-relieving medications overnight and to watch for and address sudden exacerbations with regard to heart failure or new embolisms. The cat will also need an assessment by a veterinary cardiologist to assess the underlying heart disease and prescribe medications as indicated. Many specialty centers will have a cardiologist on-site so this is another reason to transfer sooner rather than later. Of course, not every community has a specialty center conveniently located so the echocardiogram may need to be addressed by a mobile specialist, by telemedicine (over the internet), or even by a skilled non-specialist.

The cat will need to be hospitalized for at least a couple of days and possibly for as long as a week for pain management and to establish comfort and appetite before release from the hospital. Owners will need to be able to give medication and nursing care as needed.

Saddle Thrombus in the Absence of Heart Disease

We have discussed saddle thrombus in terms of heart disease so far but it turns out there are other ways to get an aortic thromboembolism. While 89 percent of cats have heart disease, 6 percent will have cancer, and 3 percent will have no apparent reason for their thrombus. The cats with cancer usually have lung cancer, which is discovered when chest radiographs are taken to assess heart disease. Lung cancer is not the only type of tumor that can induce a state promoting inappropriate clotting, though, so if heart disease is not found, a tumor search should be initiated with abdominal ultrasound. In this scenario, obviously the cat must contend with the thrombus recovery and medication to prevent future embolism, PLUS the newly discovered cancer and whatever treatments are available to address that.