Pulmonic stenosis, affectionately known as PS, is the third most common congenital heart disease in dogs. It can be accompanied by additional heart defects to create a constellation of disaster or it can be mild enough to be no more than a surprising incidental finding. Occasionally cats are affected as well.

Pulmonic stenosis refers to a constriction of the pulmonic heart valve through which blood must pass on its way from the heart to the lung.

Normal anatomy of a dog's heart. Illustration by Tamara Rees of VIN.

In order to understand what pulmonic stenosis is, it is necessary to understand some normal heart anatomy. The heart sits more or less centrally in the chest and is divided into a left side, which receives oxygen-rich blood from the lung and pumps it to the rest of the body, and a right side, which receives “used” blood from the body and pumps it to the lung to pick up fresh oxygen. Because the left side of the heart must supply blood to the whole body, its muscle is especially thick and strong, while the right side, which only pumps to one nearby area (the lungs) tends to be thinner.

When the ventricles pump, the blood from the left shoots through a valve called the aortic valve, and the blood from the right side shoots through the pulmonic valve (also called the pulmonary valve). These valves snap sharply closed after the pumping is done. The area where the blood exits the right ventricle is called the right ventricular outflow tract and consists of the exit area of the ventricle, the pulmonic valve, and the main pulmonary artery.

Pulmonic Stenosis

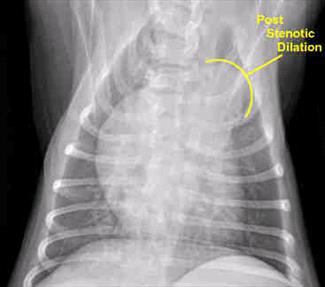

In pulmonic stenosis, the right ventricular outflow tract is narrowed either at the valve, just before it, or just after it. The most common form of pulmonic stenosis involves a deformed pulmonary valve in which the valve leaflets are too thick, the opening is too narrow, or the valve cusps are fused. The heart must pump extra hard to get the blood through this unusually narrow, stiff little valve. The right side of the heart eventually becomes thick from all this extra work and a post-stenotic dilation (a large bulging area on the far side of the narrowed valve) results from the high-pressure squirt the heart must generate to get blood through the stenosis. As the heart muscle builds up to become strong enough to pump through the stenosis, electrical conduction through the changed muscle tissue may not be normal. The rhythm of the heart’s filling and pumping cycle can be disturbed as the muscle becomes abnormal.

Predisposed breeds for this condition include Labrador retrievers, terrier breeds, miniature schnauzers, Samoyeds, English bulldogs, boxers, chow chows, beagles, cocker spaniels, basset hounds, and mastiffs.

What Does this all Mean for your Pet?

A mild pulmonic stenosis is of little concern and usually does not affect life expectancy. Luckily, most cases are mild and do not require treatment; fairly severe disease is needed for clinical signs to appear.

Approximately 35% of dogs with severe pulmonic stenosis will show some or all of the following signs:

- Tiring easily

- Fainting spells (from the abnormal electrical heart rhythm)

- Fluid accumulation in the belly

- Blue-tinge to the gums, especially with exertion

In one study, 30% of dogs with severe disease experienced sudden death.

How is a Diagnosis Made?

The turbulent blood flow resulting from the heart attempting to pump blood through the narrow pulmonic valve generates a sound called a murmur. (A murmur is not specific for pulmonic stenosis; anytime there is turbulent blood flow, it may be audible as a murmur.) If the electrical conduction of the heart is affected, the rhythm will sound irregular as well.

A murmur and abnormal rhythm picked up during a puppy's initial examination is the classic time to find the disease, but it may not become evident until later when signs of heart failure are seen. Possibly, the disease might not be detected until there are more obvious signs of heart failure present, such as fluid in the belly.

Once physical findings suggest heart disease, radiographs and, ideally, an echocardiogram follow.

puppy with pulmonic stenosis

Chest radiograph of a puppy with pulmonic stenosis. Post stenotic dilation is conspicuous. (Photo by marvistavet.com)

After the diagnosis of pulmonic stenosis is made, the next most important issue is to grade its severity. This is done with a type of ultrasound called continuous wave Doppler echocardiography. A pressure gradient across the pulmonic valve can be measured in units called millimeters of mercury (mm of Hg.) A pressure gradient of less than 40 mm of Hg generally requires no treatment at all. A gradient greater than 80 mm of Hg has a significant risk of sudden death, and therapy should be pursued (generally balloon valvuloplasty). The benefits of valvuloplasty in dogs with gradients between 40 and 80 are not as predictable. The diagnosis is clinched with the echocardiogram, where ultrasound is used to measure the diameter and thickness of the heart’s chambers. It is then easy to see the thick right ventricle and actually measure its thickness. If there is tricuspid valve disease and backward flow of blood, this can also be seen in a real-time image. A patent foramen ovale, if there is one, can also be seen (see below).

Treatment: Balloon Valvuloplasty

Clearly, if the obstruction at the pulmonic valve could be relieved, much of the problem would be solved. Severe pulmonic stenosis cases can be treated by doing just that. A balloon is inserted into the pulmonic valve where it is inflated, breaking down the obstruction. The size of the balloon catheter is determined by echocardiography as described above. Dogs that have pressure gradients of greater than 80 mm Hg across the pulmonic valve should have this procedure regardless of whether or not they are showing clinical signs. Some experts feel 60 mm Hg is a high enough gradient to warrant valvuloplasty. Dogs with concurrent tricuspid valve dysplasia benefit from this procedure regardless of their pressure gradient.

Performing this procedure reduces the risk of sudden death by 53% and improves quality of life as well. Certain types of valve deformity are not amenable to this treatment and dogs with the type of pulmonic stenosis that has a coronary artery wrapped around the pulmonary artery (the R2A anomaly - see below) are similarly not amenable to this treatment. For these dogs, unfortunately, there is no treatment that can be recommended. Balloon valvuloplasty will tear the abnormal coronary artery and alternative therapy has not been successfully developed. For these dogs, the prognosis is better without attempted therapy.

What are Possible Valvulplasty Complications/What is Suicide Right Ventricle?

If the right ventricle and its outflow tract become too thickened, a pressure gradient problem can persist after the stenosis is relieved by valvuloplasty. Suicide right ventricle is a phenomenon that occurs in a severely stenosed valve immediately after pressure is relieved by valvuloplasty. The heart muscle has grown so stiff after pumping against the stenosis valve that a new obstruction occurs. Medication and fluid therapy can help prevent this complication of valvuloplasty. Other complications of valvuloplasty include heart arrhythmias, rupture of the valve, or even puncture of the heart itself. Valvuloplasty is an advanced procedure and must be respected as such. Fortunately, serious complications are rare but it is important to be informed of potential problems, and most patients are released to go home the day of their procedure. Pressure gradients continue to drop for several months after the procedure and medication is generally needed throughout this time. It takes a good three to six months before the success of the valvuloplasty can be judged.

Treatment: Surgery

Dogs for whom the stenosis is just before the valve rather than at the valve itself may benefit from surgery. Several techniques can be used to widen the pulmonary valve or to bypass it. These procedures require an experienced surgeon and bear significant risk. The balloon valvuloplasty is the preferred treatment for cases where treatment is recommended and where balloon valvuloplasty is applicable.

Treatment: Medication

Unfortunately, medication is not very helpful for pulmonic stenosis except to manage any right-sided heart failure. In some cases, medications called beta blockers can be used in an attempt to relax the muscles of the heart and dilate the stenosis. This will not relieve the constriction but could ease it.

Pulmonic stenosis is a condition that not all veterinarians are comfortable treating. Discuss with your veterinarian whether referral to a veterinary cardiologist would be best for you and your pet.

Possible Complicating Concurrent Anatomical Problems

Concurrent Coronary Artery Constriction

Boxers and bulldogs have a type of pulmonic stenosis where a coronary artery actually wraps around the pulmonary artery exiting the heart, thus constricting it. This is called the R2A anomaly. This anomaly is of clinical importance because the coronary artery can tear if balloon valvuloplasty (see above) is attempted as a treatment.

Concurrent Tricuspid Insufficiency

Another form of pulmonic stenosis that is especially harmful involves an accompanying tricuspid valve dysplasia. The tricuspid valve is the three-leafed valve that separates the right atrium (blood-accepting chamber) from the right ventricle (the pumping chamber). Normally this valve is closed when the ventricle pumps, ensuring that all its blood pumps forward. If this valve is leaky then some of the blood, perhaps even most of it, pumps backward. If the pulmonic valve is extra tight, as in pulmonic stenosis, and the tricuspid valve is extra loose, as in tricuspid dysplasia, it is easy to see that the right ventricle must become extra strong (thick) to pump enough blood through the tight pulmonic valve, and extra large (wide) to accommodate enough blood to send an adequate amount forward, considering that most will go backward. Right heart failure is not far behind as the right side of the heart simply cannot keep up with such a double whammy of circumstances.

Concurrent Patent Foramen Ovale

Another congenital problem that can complicate pulmonic stenosis is called a patent foramen ovale. Before birth, one's oxygen comes from the mom's bloodstream (obviously, there is no breathing of air going on in the womb). The unborn heart is developing a right side (pump to the lung to pick up oxygen) and a left side (send the oxygen to the rest of the body) but during the actual development, the right and left blood mix together as there is no need for separation.

The foramen ovale is a hole in the septum of the developing heart allowing for right and left blood to mix together. Shortly after birth, when the lungs formally come into play, the foramen ovale closes up and the right and left sides of the heart are completely separated.

If the patient has pulmonic stenosis, the pressures in the right side of the heart are so high that blood is pushed from the right atrium into the left atrium with every beat of the heart, thus preventing the closure of the foramen. This allows unoxygenated blood to mix into the circuit reserved for oxygenated blood. If enough oxygen-poor blood is allowed into this circuit, the patient’s tissues may not receive enough oxygen, but generally, this is merely a mild phenomenon noticed on the echocardiogram.