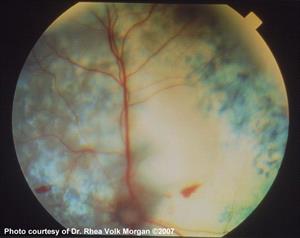

Chorioretinitis

Diffuse inflammation of the tapetal retina, focal hemorrhages and perivascular edema (cuffing) can be seen in the retina of this 3-yr-old cat with histoplasmosis.

Uveitis is an inflammation of the dark tissues (uvea) of the eye. The uvea includes the iris, the ciliary body behind the iris, and the choroid in the back of the eye behind the retina.

Uveitis can be acute or chronic in onset, and anterior (iris and ciliary body) or posterior (choroid and retina) in location. Occasionally, all uveal tissues are involved (panuveitis). Anterior uveitis can cause obvious symptoms, such as a red eye, blinking/squinting from pain, cloudiness and changes in the appearance of the pupil/iris. Secondary glaucoma can also develop. Posterior uveitis may only be recognized during an eye exam unless blindness occurs.

Uveitis has many different causes, including infectious diseases such as bacterial, viral, fungal, rickettsial and protozoal infections. Penetrating trauma, bleeding into the eye, long-standing cataracts, ingestion of fatty foods, immune-mediated diseases, generalized systemic diseases, and cancer of the eye are also potential causes. Occasionally, a cause is never identified.

Any age, sex or breed of dog or cat can develop uveitis. The underlying causes, however, can be influenced by the pet's age, sex, breed, the geographic region in which it lives, and the environment.

Diagnosis

Figuring out why a pet has uveitis can be challenging. Unless the cause is obvious on the eye exam (such as a cat scratch, tumor, hypermature cataract), a thorough physical examination is required to search for evidence of disease elsewhere in the body. Numerous tests (complete blood count, biochemistry profile, serology for infectious diseases), x-rays (chest, abdomen), and possibly an abdominal ultrasound may also be needed. If the front of the eye is so cloudy that the structures in the back of the eye cannot be seen, then an ultrasound may be recommended. Ophthalmology requires specialized equipment, and your veterinarian may refer your pet to a veterinary ophthalmologist.

Treatment

The goal of treatment is to resolve the uveitis and any underlying causes. Immediate priorities are to relieve pain, prevent glaucoma, maintain the normal internal structure of the eye and preserve vision. Treatment usually involves topical eye drops and systemic medications. Therapy is often required for weeks or months. Occasionally, treatment is lifelong. Surgery to remove the eye is rarely required; that is most often indicated for eyes that are permanently blind and painful, have a tumor, or when the inflammation cannot be controlled.

Monitoring

Because pets that have uveitis are at risk for vision problems and treatments often must be tweaked, close monitoring is important. Monitoring involves frequent ophthalmic examinations, including eye pressure measurement to check for glaucoma. Repeated laboratory tests may be required, depending upon the underlying cause and the therapy used.

Prognosis

Prognosis is good to guarded depending on the underlying cause, severity, extent of damage caused by the inflammation, duration of inflammation, response to therapy, and development of negative aftereffects. The best outcome occurs when uveitis is diagnosed early, treated promptly and aggressively, and the underlying cause is responsive to therapy.