The Normal Pancreas and What it Does

Normal Pancreas

Graphic by MarVistaVet

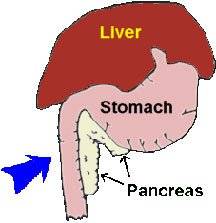

The pancreas is a pale pink glandular organ that nestles cozily just under the stomach and along the first portion of the small intestine. As a glandular organ, the pancreas is all about the secretion of biochemicals, and it has two main jobs: the first job is the secretion of digestive enzymes to help us break down the nutrients we eat. The second job is the secretions of insulin and glucagon (hormones that regulate how we actually use the nutrients we have eaten). It is the first job (the digestive enzyme part) that concerns us in pancreatitis.

So, let's go back to the beginning of digestion. We eat food, chew it up into a slurry, and swallow it. It travels down the esophagus to the stomach, where it is ground up further, and enzymes are added to begin the breakdown of nutrients into pieces (basically into molecules) small enough for us to absorb. Digestion continues as the food moves down into the small intestine, where stomach acid is neutralized, and further digestive enzymes are added (thanks to the pancreas). Food moves down the small intestine further, and the focus shifts from nutrient digestion to nutrient absorption. By the time the food has reached the large intestine, it is just undigestible waste and water. The large intestine absorbs the water, and its bacteria may be able to break down some of the waste. After that, food comes out the other end into the toilet or litter box.

So, the normal pancreas makes and stores digestive enzymes for use when you need your meal digested. Keep in mind these enzymes are powerful and made to break down food. Imagine if they escaped and tried to break down the pancreas itself! Unfortunately, that is what happens in pancreatitis.

Canine Pancreas

Graphic by VIN

Pancreatitis is Inflammation of the Pancreas

In pancreatitis, inflammation disrupts the normal integrity of the pancreas. Digestive enzymes are normally stored safely as inactive forms within pancreatic granules so that they are harmless but in pancreatitis, they are prematurely activated and released internally, digesting the body itself.

The result can be a metabolic catastrophe. The living tissue becomes further inflamed, and the tissue damage quickly involves the adjacent liver. Toxins released from this rampage of tissue destruction are liberated into the circulation and can cause a body-wide inflammatory response. If the pancreas is affected so as to disrupt its ability to produce insulin, diabetes mellitus can result; this can be either temporary or permanent.

Specific Pancreatitis Disasters

- A syndrome called Weber-Christian syndrome results, in which fats throughout the body are destroyed with painful and disastrous results.

- Pancreatitis is one of the chief risk factors for the development of what is called disseminated intravascular coagulation or DIC, which is basically a massive uncoupling of normal blood clotting and clot dissolving mechanisms. This leads to abnormal simultaneous bleeding and clotting of blood throughout the body.

- Pancreatic encephalopathy (brain damage) can occur if the fats protecting the central nervous system become digested.

Inflamed Pancreas

A swollen, inflamed pancreas with areas of hemorrhage. Graphic by MarVistaVet

The good news is that most commonly, the inflammation is confined to the area of the liver and pancreas but even with this limitation, pancreatitis can be painful and life-threatening.

Pancreatitis can be acute or chronic, mild or severe.

What Causes Pancreatitis

In most cases, we never find out what causes it, but we do know some events that can cause pancreatitis.

-

The area of the small intestine where the pancreas secretes its enzymes is called the "duodenum." A small tube called the "pancreatic duct" transports pancreatic enzymes into the duodenum. Backwash (reflux) of duodenal contents backward up into the pancreatic duct can create inflammation in the pancreas.

-

The pancreas has numerous safety mechanisms to prevent self-digestion. One of these mechanisms is the fact that the enzymes it creates are stored in an inactive form. They are harmless until they are mixed with activating enzymes made by the duodenum. If duodenal fluids backwash up the pancreatic duct and into the pancreas, enzymes are prematurely activated, and pancreatitis results. This is apparently the most common pancreatitis mechanism in humans, though it is not very common in veterinary patients.

- Concurrent hormonal imbalance predisposes a dog to pancreatitis. Such conditions include Diabetes mellitus, hypothyroidism, and hypercalcemia. The first two conditions are associated with altered fat metabolism, which predisposes to pancreatitis, and the latter condition involves elevated blood calcium that activates stored digestive enzymes.

- Use of certain drugs can predispose to pancreatitis (sulfa-containing antibiotics such as trimethoprim sulfa, chemotherapy agents such as azathioprine or L-asparaginase, and the anti-seizure medication potassium bromide). Exposure to organophosphate insecticides has also been implicated as a cause of pancreatitis. Exposure to steroid hormones has traditionally been thought to be involved as a potential cause of pancreatitis but this appears not to be true.

- Trauma to the pancreas that occurs from a car accident or even surgical manipulation can cause inflammation and, thus, pancreatitis.

- A tumor in the pancreas can lead to inflammation in the adjacent pancreatic tissue.

- A sudden high-fat meal is the classic cause of canine pancreatitis. The sudden stimulation to release enzymes to digest fat seems to be involved.

- Obesity has been found to be a risk factor because of the altered fat metabolism that goes along with it.

- Miniature Schnauzers are predisposed to pancreatitis as they commonly have altered fat metabolism.

Signs of Pancreatitis

The classical signs in the dog are appetite loss, vomiting, diarrhea, a painful abdomen, and fever or any combination thereof. Pancreatitis can come on suddenly and seemingly out of nowhere or it can be a smoldering on-going condition that waxes and wanes.

Making the Diagnosis

Lipase and Amylase Levels (no longer considered reliable)

A reliable blood test has been lacking for this disease until recently. Traditionally, blood levels of amylase and lipase (two pancreatic digestive enzymes) have been used. When their levels are especially high, it's reasonable sign that these enzymes have leaked out of the pancreas, and the patient has pancreatitis, but these tests are not as sensitive or specific as we would prefer. Amylase and lipase can elevate dramatically with corticosteroid use, with intestinal perforation, kidney disease, or even dehydration. Some experts advocate measuring lipase and amylase on fluid from the belly rather than on blood but this has not been fully investigated and is somewhat invasive.

Pancreatic Lipase Immunoreactivity

A newer test called the PLI, or pancreatic lipase immunoreactivity, test has come to be important. As mentioned, lipase is one of the pancreatic digestive enzymes and only small traces are normally in the circulation. These levels jump dramatically in pancreatitis, which allows for the diagnosis to be confirmed with a non-invasive and relatively inexpensive test. The PLI test is different from the regular lipase level because the PLI test measures only lipase of pancreatic origin and thus is more specific. The problem is that technology needed to run this test is unique and the test can only been run in certain facilities on certain days. Results are not necessarily available rapidly enough to help a sick patient.

The PLI, or pancreatic lipase immunoreactivity, test has come to be important. Photo courtesy of National Institutes of Mental Health, Department of Health and Human Services

Spec CPL and DGGR Lipase Assay

More recently a new test called the SPEC cPL (specific canine pancreatic lipase) test has become available. This test is a newer generation immunological test for canine pancreatic lipase and can be run overnight by a reference lab. This test is able to detect 83 percent of pancreatitis cases (the test is 83 percent sensitive) and excludes other possible diseases in 98 percent of cases (i.e. the test is 98 percent specific for pancreatitis). The CPL test has been adapted into an in-house test kit and can be run in approximately 30 minutes. Some kits provide a numeric value while others are simply positive or negative depending on whether the CPL level surpasses the normal level. These kits have made diagnosis of pancreatitis much more rapid and convenient.

A similar lipase assay called the DGGR Lipase Assay (Precision PSL® test). This test can be run at a reference laboratory with results obtained usually overnight; there is no in-hospital test kit.

The diagnosis of pancreatitis is not made solely on the basis of a lab test. These tests are not used to screen patients that are not sick; the entire clinical picture of a given patient is considered in making this or any other diagnosis.

Imaging

Dr. Jon Perlis of DVMSound performs an ultrasound exam on a dog. Photo by MarVistaVet

Radiographs can show a widening of the angle of the duodenum against the stomach, which indicates a swelling of the pancreas. Most veterinary hospitals have the ability to take radiographs but this type of imaging is not very sensitive in detecting pancreatitis and only is able to find 24 percent of cases.

Ultrasound, on the other hand, detects 68% of cases and provides the opportunity to image other organs and even easily collect fluid from the belly. Since pancreatitis can be accompanied by a tumor near the pancreas, ultrasound provides the opportunity to catch such complicating factors.

In some cases, surgical exploration is the only way to make the correct diagnosis.

Treatment

The most important feature of treatment is aggressively rehydrating the patient with intravenous fluids as this restores the circulation to the pancreas and supports the natural healing mechanisms of the body. This means that the best route to recovery involves hospitalization. Fluids are continued until the patient is able to reliably drink and hold down adequate fluid intake, a process that commonly takes the better part of a week. Pain and nausea medication is needed to keep the patient comfortable, restore interest in food, and prevent further dehydration.

Plasma transfusion is somewhat controversial in treating pancreatitis. On one hand, plasma replenishes some of the natural blood proteins that are consumed by circulating digestive enzymes and would seem to make sense. In humans with pancreatitis, however, no benefit has been shown with plasma transfusion. Whether or not the protection afforded by plasma is real or theoretical is still being worked out. Higher mortality has been associated with patients receiving plasma, but this may be because they were sicker than patients who did not receive plasma to begin with.

Drawing by Dr. Wendy Brooks

In the past, nutritional support was delayed in pancreatitis patients as it was felt that stimulating the pancreas to secrete enzymes would encourage on-going inflammation, but this theory has been rethought. Currently, an earlier return to feeding has been found to be beneficial to the GI tract's ability to resume function. If nausea controls through medication does not give the patient a reasonable appetite, assisted feeding is started using a fat-restricted diet. Return of food interest and resolution of vomiting/diarrhea generally means the patient is ready to return to the home setting. Low-fat diets are crucial to managing pancreatitis, and their use should be continued for several weeks before attempting to return to regular dog food. Some dogs can never return to regular dog food and require prescription low-fat foods indefinitely.

Pancreatitis is a highly inflammatory disease. Fever, elevated white blood cell (WBC) count, and other signs of inflammation occur frequently in patients with pancreatitis. Infection is rare in pancreatitis, but when it does happen, it can lead to serious complications. Your veterinarian can help decide if antibiotics are needed, but in most uncomplicated cases, they are not part of the treatment regimen.

Supportive care includes more than just intravenous fluids. Nausea medication, pain relief, and possibly protecting the stomach from ulceration are all commonly included in the treatment plan. The specifics will be individually tailored for each situation.

Panoquell-CA1® (fuzapladib sodium) is a new product released in 2023 for the treatment of acute pancreatitis. It is given by IV injection for the first 3 days of hospitalization. Heretofore, treatment has been "supportive," which means we make the patient comfortable with symptomatic relief and support the circulation through the pancreas with IV fluids until the pancreas can heal on its own. This new medication represents actual treatment in that it prevents harmful white blood cells from entering the pancreas where they would release their own inflammatory biochemicals. This treatment is meant to actually stop the inflammation in the pancreas. It is used for acute/sudden severe cases and not for ongoing milder cases.

How Much Fat is Okay?

There are several ultra-low fat diets made for pancreatitis patients, and your veterinarian will likely be sending your dog home with one of them. Remember that pancreatitis is a diet-sensitive disease so it is important not to feed unsanctioned foods, or you risk a recurrence. If your dog will not eat one of the commercial therapeutic diets, you will either need to home-cook or find another diet that is appropriately low in fat (less than 7 percent fat on a dry matter basis). In order to determine the fat content of a pet food, some calculation is needed to take into consideration how much moisture is in the food.

The Guaranteed Analysis on the bag or can of food will have two values that we are interested in: the % moisture and the % crude fat. To determine the % fat in the food, you must first determine the % dry matter of the food. This is done by subtracting the moisture content from 100. For example, if the moisture content is 15%, the dry matter is 85%. If the moisture content is 75%, the dry matter is 25%, and so on.

Next, take the % crude fat from the label and divide the % crude fat by the % dry matter. For example, if the moisture content is 76%, this means the dry matter is 24%. If the crude fat content is 4%, the true fat content is 4 divided by 24 which =0.16 (16%). Such a food would be way too high in fat for a dog with pancreatitis. You want the number to be 0.07 (7%) or less. Simply reading the fat content off the label does not take into account the moisture content of the food and will not tell you what you need to know. If this is too much math, the staff at your vet's hospital can help you out.

When in doubt, canned chicken, fat-free cottage cheese and/or boiled white rice will work in a pinch. Eventually, there will be a point where the tests will be repeated. At that point, it will be determined if the patient has chronic pancreatitis and will need long-term dietary modification or if the episode has concluded. The safest diet going forward will be therapeutic low-fat diets used during the acute episode, but if you want to transition to a conventional diet, this can be done. If you restart a regular diet, it is best to recheck pancreatitis testing in a few weeks to be sure that there is no recurrence on the horizon. Alternatively, a diet with a moderate fat restriction (15% by dry matter, as calculated above) might make for a happy medium.

Beware of Diabetes Mellitus

When the inflammation subsides in the pancreas, some scarring is inevitable. When 80% of the pancreas is damaged to the extent that insulin cannot be produced, diabetes mellitus results. This may or may not be permanent, depending on the capacity of the pancreas’ tissue to recover.

In Summary

- Pancreatitis is inflammation of the pancreas. The pancreas secretes digestive enzymes that break down nutrients.

- If digestive enzymes are activated too early, they can digest the body itself instead of food.

- It can be painful and life threatening as well as acute or chronic, mild or severe.

- Signs include appetite loss, vomiting, diarrhea, painful abdomen, and fever.

- Certain additional problems can occur, such as affecting the lung to the point of respiratory failure.

- In most cases the cause is unknown but these issues can contribute: Backwash (reflux), hormonal imbalances, certain drugs, trauma, pancreatic tumor, sudden high fat meal, or obesity.

- Diagnosis is generally made with lab tests. Ultrasound is more useful than radiographs. Sometimes surgery is the only way to diagnose it.

- Treatment is rehydrating with IV fluids to restore the circulation, which generally means being hospitalized for almost a week. Pain and anti-nausea medications are needed.

- After release, your dog will need an ultra low-fat diet that your veterinarian will provide.

- When 80% of the pancreas is damaged and insulin cannot be produced, diabetes results.

Back to top