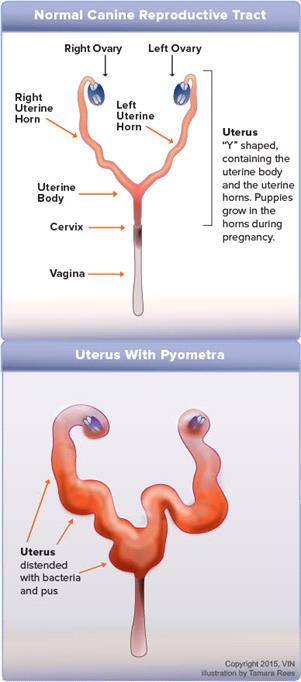

Pyometra illustration vertical

The word pyometra is derived from the Latin “pyo,” meaning pus, and “metra,” meaning uterus. A pyometra is an abscessed, pus-filled, infected uterus. Toxins and bacteria leak across the uterine walls and into the bloodstream, causing life-threatening toxic effects. The uterus dies, releasing large amounts of pus and dead tissue into the abdomen. Without treatment, death is inevitable. Preventing this disease is one of the main reasons for routinely spaying female dogs.

What Might Make Your Veterinarian Suspect this Infection?

Classically, the patient is an older female dog. Usually, she has finished a heat cycle in the previous 1 to 2 months. She has a poor appetite and may be vomiting or drinking an excessive amount of water.

There are two forms of pyometra: "open" and "closed, with open being the most common. With an open pyometra, the cervix is open, allowing for pus to drain outside the body. Because the pus can drain, the patient is usually not as sick, plus with the noticeable smelly vaginal discharge, the patient will likely be seen by the vet sooner. With a closed pyometra, the cervix is closed, and the toxic pus is held within the body. Diagnosis is trickier without the obvious discharge, and the patient will be sicker from the toxins.

Lab work shows a pattern typical of widespread infection that is often helpful in narrowing down the diagnosis. Radiographs may show a gigantic distended uterus, though sometimes this is not obvious, and ultrasound is needed to confirm the diagnosis.

How Does this Infection Come About?

A radiograph showing a closed pyometra.The large outlined structure is the pus-filled uterus. A normal uterus is too small to be seen on a radiograph. Photo courtesy of Alta Mesa Animal Hospital.

With each heat cycle, the uterine lining engorges in preparation for pregnancy. Eventually, some tissue engorgement becomes excessive or persistent (a condition called cystic endometrial hyperplasia). This lush glandular tissue is ripe for infection (recall that while the inside of the uterus is sterile, the vagina below is loaded with bacteria). Bacteria ascend from the vagina and the uterus becomes infected and ultimately filled with pus. Hormonal effects on the uterine tissue accumulate with each heat cycle, which means pyometra is much more common in older females because they have experienced many hormonal cycles.

Traditional Treatment: Surgery

The usual treatment for pyometra is surgical removal of the uterus and ovaries. It is crucial that the infected uterine contents do not spill and that no excess bleeding occurs. The surgery is challenging, especially if the patient is toxic. Antibiotics are given at the time of surgery and may or may not be continued after the uterus is removed. Pain relievers are often needed post-operatively. A few days of hospitalization are typically needed after the surgery is performed.

It is especially important that the ovaries be removed to prevent future hormonal influence on any small stumps of uterus that might be left behind. If any portion of the ovary is left, the patient will continue to experience heat cycles and be vulnerable to recurrence.

Pyometra

Pus-filled uterus after removal from a dog.

Image courtesy MarVistaVet

While the end result of pyometra surgery is a spayed dog, there is nothing routine about a pyometra spay. As noted, the surgery is challenging and the patient is in a life-threatening situation. For these reasons, the pyometra spay typically costs five to ten times as much as a routine spay.

Pros of Emergency Surgery:

- The infected uterus is resolved rapidly (in an hour or two of surgery).

- Extremely limited possibility of disease recurrence.

Cons of Emergency Surgery:

- Surgery must be performed on a patient who could be unstable.

Alternative Treatment: Prostaglandin Injections

In the late 1980s, another protocol became available that might be able to spare a valuable animal’s reproductive capacity. Here, hormones called prostaglandins are given as injections to cause the uterus to contract and expel its pus. A week or so of hospitalization is necessary, and some cramping discomfort is often experienced. This form of treatment is not an option in the event of a closed pyometra because the closed cervix prevents drainage of the infected material, even in the face of prostaglandin contractions. Further, the dog must be bred on the next heat cycle. If she is not bred or does not conceive puppies on the next heat cycle, the recurrence rate of pyometra may be as high as 77%. After recovery from pyometra, the uterus is damaged and may not carry a litter normally; pregnancy rates are only 50-65%. Unless the dog has great value to a breeding program, it may not be worth it to attempt prostaglandin treatment.

Pros of Prostaglandin Treatment:

- There is a possibility of future pregnancy for the patient (though often there is too much uterine scarring).

- Surgery can be avoided in a patient with concurrent problems that pose extra anesthetic risk.

Cons of Prostaglandin Treatment:

- Pyometra can recur.

- The disease is resolved more slowly (over a week or so).

- There is a possibility of uterine rupture with the contractions. This would cause peritonitis and escalate the life-threatening nature of the disease.

- Breeding should occur on the very next heat cycle.

Prevention

Spaying represents complete prevention for this condition. The importance of spaying cannot be over-emphasized. Often an owner plans to breed a pet or is undecided, time passes, and then they fear she is too old to be spayed. The female dog or cat can benefit from spaying at any age. The best approach is to figure that pyometra is highly likely to occur if the female pet is left unspayed; any perceived risks of surgery are very much out-weighed by the risk of pyometra.

____________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________

Feline Pyometra

Siamese cat with tag

Photo courtesy Dr. Teri Ann Oursler

Female cats may also fall victim to pyometra. In cats, the disease is just as serious and the treatment options are the same. There is an important difference for cats with pyometra, however: female cats rarely appear sick until the very late stages of the disease. The classic creamy vaginal discharge is present, and often, the belly appears distended because of the size of the pus-filled uterus, but the cat herself is generally eating and grooming as if nothing much is going on. If the female cat is fastidious and cleans away the discharge, the pet owner may wrongly conclude that she is simply pregnant. Unfortunately, this lack of apparent illness leads to a delay in diagnosis, and this delay can be lethal.

As with dogs, diagnosis is usually by radiography, though ultrasound can be used, particularly if radiography is ambiguous. Treatment for cats is similar to treatment for dogs: surgery is traditional, but prostaglandins may be used if it is important to preserve the cat's ability to breed.

A Few Words about Stump Pyometra

After a pet is spayed, there is frequently a small stump of uterine tissue inside the abdomen where the tract has been tied off. As long as there are no female hormones in play, this small stump will be inactive and cannot develop a pyometra. If, on the other hand, there are hormones in circulation, a pyometra can develop in the stump. Symptoms are similar to those for a uterine pyometra (vaginal discharge, fever, etc.) except that the patient has been spayed sometimes years prior.

Treatment is surgical removal of the infected stump, but the real problem is the source of estrogen or progesterone that was necessary to create the condition in the first place. This source of hormone must be identified. Sometimes, a small portion of the ovary is left behind or even re-grows spontaneously after spaying, creating what is called ovarian remnant syndrome. This sounds like a surgical error but the situation is usually more complicated and the remnant can be microscopic. Alternatively, there are many estrogen-containing topical products for human use to which a pet can become exposed through licking or cuddling. Occasionally, progestins are used in cats to control skin disease though these have generally been supplanted by newer medications.

Stump pyometra is suspected when a mass is seen on radiographs or ultrasound in the area of the uterine stump and there are accompanying clinical signs of pyometra. If surgery ensues to remove the stump and there is no obvious exposure to a hormone-containing product, the area of the ovaries is explored for evidence of ovarian remnant. If no remnant is visible, sometimes biopsies are taken to rule out microscopic remnants. Once the hormone source is gone, there should be no further pyometra risk.