Research subjects

Photo by Dr. Joseph Bernstein

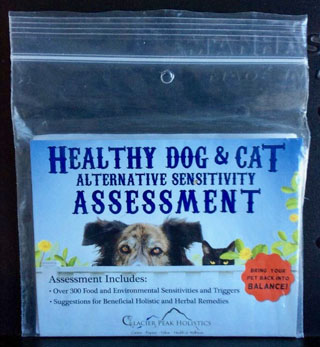

Synthetic fur samples from these five stuffed animals yielded test results suggesting that they have food or environmental allergies.

As the father of three children, Dr. Joseph Bernstein has been known to buy toys from time to time. But it was in his capacity as a veterinary dermatologist that he found himself not long ago shopping for premium stuffed animals, the kind with realistic-looking fur.

The project: An investigation into a business that sells a direct-to-consumer test purporting to assess dogs' and cats' "stressors and triggers" by analyzing their hair and saliva.

Bernstein, who practices in Maryland, sympathizes with pet owners who want a quick and easy allergy test for their itchy, restless animals. But he has no sympathy for companies that he believes prey upon pet owners' desperation.

Exasperated by the flow of clients coming into his clinic with what looked to be bogus test results, Bernstein began ordering the tests himself to investigate their validity, submitting real and fake fur and saliva.

Letters

The results, published Jan. 24 by the international peer-reviewed journal Veterinary Dermatology, confirmed Bernstein's hunch. He and three collaborators concluded that the test they evaluated "lacks precision, accuracy and repeatability and should not be used in the diagnosis or treatment of allergic conditions in companion animals."

Bernstein said in an interview that he worries that pet owners are being defrauded by companies selling unvalidated and inaccurate tests. Such clients, he said, are "desperate. People who own atopic animals, they're miserable. They're not sleeping [because] the dog's not sleeping. So if someone offers you a magic test and you get your answer, great!"

While skin and blood tests are available for environmental allergies in veterinary patients, there are no validated diagnostic tests for food allergens. Pursuing a diagnosis can be lengthy, tedious and difficult. It involves eliminating in the patient's diet all foods and food ingredients known to be allergenic, then carefully reintroducing them one at a time and monitoring for reactions.

"It's a process," acknowledged Dr. Mark Rishniw, a study co-author. "There's no shortcut. There's no magic wand that you can wave over them. It's frustrating often. It requires extreme diligence. Skin testing or exposure testing is still the test of choice [to diagnose allergies] both in humans and animals. They're not perfect but they're the best we've got."

Rishniw is an internal medicine and cardiology specialist on the faculty of Cornell University College of Veterinary Medicine and director of research at the Veterinary Information Network, an online community for the profession and parent of the VIN News Service. VIN funded Bernstein's study.

The research focused on a "Pet Wellness Life Stress Scan" sold for $107.95 by Glacier Peak Holistics in Eureka, Montana. According to the Glacier Peak website, the scan "is so much more than an allergy test for dogs and cats as it can identify imbalances and disturbances within the entire body." The test is said to use "biofeedback, which has the ability to read the energetic resonance that emanates from the hair and saliva samples."

To test the test, researchers submitted 35 samples. Some were fur and saliva from dogs and cats known to have atopy, or allergies. Some were fur and saliva from dogs and cats known to be healthy. And some were synthetic fur from stuffed animals, and sterile saline solution. The researchers also submitted duplicate samples from some live animals, using different names, to test whether the business would provide duplicate or divergent results for a single animal.

The researchers reported: "The company provided results for all submitted samples, including those comprising synthetic fur from toys and saline."

In other words, the faux fur and false saliva were found to have "stressors and triggers" on par with the samples from live animals.

Also, the results for the live animals whose samples were submitted a second time under different names were inconsistent. "Our study found that pairs of samples from real animals were no more similar than between any two [different] animals or between a real animal and fake fur," Rishniw said.

The overall results tended to follow a particular pattern, regardless of the sample source, the researchers said. "... certain dietary triggers ... [were] over-represented in both the real animals and synthetic fur and saline samples," they wrote. "Specifically, chicken, salmon, shellfish, dairy products, grains, ethoxyquinol, food colourings and food preservatives were identified in more than 60 percent of the samples, regardless of the source of the sample (animal or toy). ... Other triggers, such as fruits, nuts and vegetables, were rarely identified in any sample."

Because the results were so similar, the researchers speculated that no analysis was conducted; rather, the results appeared to be pre-determined. "I suspect that there's no actual testing done and that this is a philosophical bias by the company," Rishniw said in an interview. "... Things like chicken I think approached close to 100 percent. Grains approached close to 100 percent. Whereas things a vegan would consider good stuff, that's where there were rarely triggers."

As for the biofeedback method Glacier Peak says it uses, the researchers state in the study: "We could find no peer-reviewed published research studies supporting the use of biofeedback analysis on hair or saliva samples for health diagnosis or treatment. Thus, it is unknown what potential factors could have resulted in the identification of positive results on synthetic hair and sterile saline samples by this company."

Some holistic veterinarians support the approach

Glacier Peak Holistics is a business name used by Pet Wellness Inc., a corporation formed in Montana in 2012. The founder and CEO is identified on the business website as Deb Gwynn, a "certified herbalist" and "pet food nutrition specialist."

VIN News could not reach Gwynn for comment. A person who answered the telephone at the business said Gwynn was unavailable. The person identified herself as the office manager, Brittainy Miller. She said Gwynn is aware of the study.

Responding to questions raised by the study, Miller said, "We're not testing for allergies. We're doing biofeedback that tests for stress."

She said the test is based on "energetic medicine. Everything has energy," she explained, "so no matter what is submitted, that will have results. Any time anybody submits false information, you'll get a false reading. If they're deliberately sending in stuffed pet hair and things that aren't necessarily from an animal, you'll get a report, but you'll have false results."

She added, "We're not veterinarians here. We don't tell people we're veterinarians. We are dealing in biofeedback, which is based on biophysics. ... Everything has energy. We learned that in school. A stapler has energy. Everything is made up of atoms, and everything has energy." She added that contamination with DNA also could cause synthetic fur to produce a false positive test result.

Miller said the company has performed "over 25,000 scans to date" in dogs, cats and horses, and has received "testimonials from pet parents on a daily basis on how it's helped their animals get better."

Asked whether the business has obtained scientific validation for its method, Miller replied, "Nope, just feedback from our pet parents."

She pointed out that a number of holistic veterinarians, whose practices are listed on the Glacier Peak website, recommend and/or carry the company's products. Miller added, "Conventional veterinarians who do not practice integrative medicine don't understand how biofeedback works."

Bernstein said support among some practitioners of Glacier Peak's approach is "[o]ne of the more difficult aspects of this situation." The endorsements perplex him in light of a company disclaimer that the test "should not be used to diagnose, treat or cure any disease." And yet, he said, the test is "being commonly used for exactly those purposes."

Interactions with veterinarians who recommend the approach spurred Bernstein to take a close look at the Glacier Peak test. He decided to submit fake samples to the business to see what would result. With his then 6-year-old daughter’s permission, he trimmed some fur from one of her abandoned stuffed animals and sent it in, along with sterile saline in place of saliva. The submission yielded a list of “stressors, triggers and energetic imbalances" for the toy, motivating Bernstein to expand the study to make it scientifically robust.

In order not to arouse suspicions, Bernstein and his collaborators — Rishniw; Dr. Kathy Tater, a dermatology consultant at VIN; and Dr. Rodrigo Bicalho, an associate professor in the Department of Population Medicine and Diagnostic Sciences at Cornell University veterinary college — enlisted volunteers around the country to order test kits and submit samples that were prepared by the research team. (Members of the VIN News Service staff, including the author of this article, helped to recruit some volunteers.)

With the false fur samples, Bernstein took a variety of precautions to avoid biological contamination. For example, upon purchasing five new stuffed animals for the study, he placed them immediately in plastic bags and sealed the bags. When handling the toys, he wore gloves. And he examined the fur samples under a microscope to confirm that they were synthetic and free of dust mites, storage mites and molds.

ImmuneIQ drew similar scrutiny

Challenging a direct-to-consumer hair-and-saliva allergy test by submitting faux fur and saliva was an idea Bernstein borrowed from two veterinary dermatology colleagues.

A few years earlier, those dermatologists, Dr. Kimberly Coyner and Dr. Anthea Schick, had submitted authentic and false fur and saliva to a company in Boulder, Colorado, called ImmuneIQ. The company claimed to analyze samples using "a highly proprietary multi-stage process" to assess "how the animal immunologically and energetically reacts to the environment it is in."

Like Glacier Peak Holistics, ImmuneIQ produced results for the fake fur and false saliva. It also identified allergic sensitivities in a dog that had no allergies. And it failed to yield consistent results for dogs whose samples were submitted repeatedly.

Coyner and Schick presented their findings at the 8th World Congress of Veterinary Dermatology in France in 2016, and their work was published in the peer-reviewed Journal of Small Animal Practice last October.

Separately, a veterinarian in Alaska lodged a complaint about ImmuneIQ with Colorado regulators in 2015, prompting an investigation that led to the state Board of Veterinary Medicine issuing a cease-and-desist order to the company, its founder, and a Las Vegas veterinarian associated with the company. By the time the order was issued in June 2017, however, the business already had closed.

Glacier Peak

Photo by Dr. Laurie Martin

A test kit Dr. Laurie Martin bought in 2015 contained cotton swabs, a plastic comb, return bags and an information sheet. The name of the test has changed over the years.

Bernstein and his study collaborators are not the only veterinarians to challenge the Glacier Peak Holistics hair-and-saliva test. A few years ago, Dr. Laurie Martin, a practitioner in Illinois, decided to test the test after she read about it in an online forum frequented by pet owners.

Some forum participants advised forgoing veterinary advice on dogs that appeared to be allergic and instead run Glacier Peak's test, which they maintained would give a definitive answer about their dog's problems, Martin recalled in an interview.

Curious, Martin purchased a test kit at a local pet store. The kit consisted of three cotton swabs, a plastic comb, return bags and an information sheet. She pulled fibers from one of the cotton swabs, submitting that as fur. In lieu of saliva, she submitted Lactated Ringers Solution, a fluid used in IV bags.

Recounting the experience in an online message board of VIN, Martin wrote: "I thought that the company may contact me to report an error message of some sort but instead I received a report outlining all my pet's problems and which supplements were recommended." (The supplements are sold by Glacier Peak Holistics.)

Martin told VIN News that when she posted the outcome on the pet forum, participants were indignant and furious — at her. One wrote something to the effect of, "You are such an unethical person for sending in phony samples to mess up their test."

"When people have these strong beliefs," Martin observed, "no matter what you show them ... they'll more strongly defend their beliefs and attack the information."

Bernstein and Rishniw said they realize that some people — veterinarians and pet owners alike — may remain steadfast in their trust in the hair-and-saliva assessments.

"If you're of the mindset that will believe in this stuff, you're not our target audience — it becomes a quasi-religious argument," Rishniw said. "But if you're simply uninformed and naive about it, or ignorant about it, then hopefully, this [study] will help point you in the right direction."

Editor's note: This article has been changed from the original to remove comments from a source who did not intend to speak on the record.