Mike K. Holgate, BVetMed, CertVC, MRCVS

Recent advances in cardiopulmonary diagnostics make it easy to overlook the importance of physical examination. Electrocardiography, echocardiography, bronchoscopy, radiography and clinical pathology do not negate the importance of information obtained from effective examination and auscultation, at relatively minimal cost.

Equipment

A good stethoscope is mandatory for accurate auscultation, as is a good sense of hearing! Different types and models of stethoscope are available, traditional and electronic. One gets what one pays for. The author uses single tube stethoscopes in a variety of bell/diaphragm sizes depending on patient size. These vary from infant, through paediatric, to full size. Some may be 'dual', having a separate bell and diaphragm; or combined in one face, with the listening surface varied by the pressure applied. Some users prefer dual-tube types. Electronic stethoscopes amplify the audible signal and allow recording of the phonocardiogram to computer. These allow less easily audible sounds to be amplified and detected. They have the drawback that pathological muffling of heart and lung sounds may be disguised by amplification.

A stethoscope should be the user's 'property' and used for every patient so the characteristics of the instrument are known. The ear tips should be comfortable and fit tightly enough to exclude extraneous noise. Usually the ear pieces are angled forwards. Tube length should be minimised to reduce signal loss, 36-50 cm is generally recommended, but it can be cut if overlong.

The diaphragm, designed to detect higher frequency noise, is used for the majority of the examination. The bell is employed to maximise low-frequency noise such as local murmurs or gallop sounds.

How to Auscultate

Ideally a quiet room is required to minimise noise intrusion. Artefacts are mainly due to external noise. It is worth asking for quiet before auscultation and for clients to avoid stroking or touching their pet. Friction artefact between the stethoscope 'head' and the patient's hair coat mimics lung sounds. Panting may necessitate holding the patient's mouth closed. Purring in cats may be rectified by gently blowing air in their face, running a tap or dabbing surgical spirit on the patient's nose.

Dogs and cats are best auscultated standing (or sitting), rabbits sitting. However, sitting superimposes the forelimbs over the point of maximal intensity (PMI) of cranially situated sounds, and may alter the heart position due to diaphragmatic pressure. Lateral recumbency allows the heart to fall to the dependent side, altering its position and that of the heart sounds. Palpating the femoral pulse during auscultation may aid differentiation of heart sounds and lung sounds from other noise, and recognition of pulse deficits. Observing the animal's respiratory pattern may allow the differentiation of lung sounds from cardiac murmurs.

Normal Sounds

Normal small animal heart sounds consist of two sounds; S1 and S2. S1 is due to atrioventricular (AV) (mitral and tricuspid) valve closure early in systole, S2 is due to semilunar (aortic and pulmonic) valve closure and occurs late in systole. S1 is louder at the left apex, S2 at the left heart base. S3 and S4 sounds may be heard although these are rare in healthy small animals.

Normal lung sounds are usually audible dorsal to the heart base but may be inaudible in healthy small animals. Puppies and kittens may have considerable lung noise which may mimic disease. Normal inspiratory sounds are soft and low-pitched. Expiratory sounds may be even softer and lower in pitch. Normal sounds are described as bronchial and vesicular sounds. Bronchial sounds are similar to tracheal sounds generated by the major airways. Vesicular sounds, like 'wind through trees', are softer, and are heard more peripherally.

Where to Listen

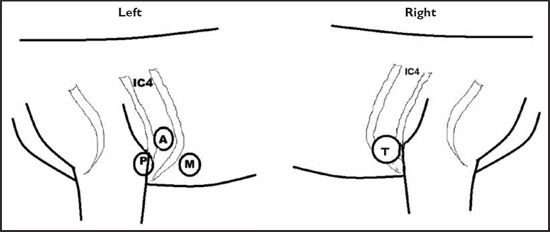

See Figure 1.

On the left, the pulmonary valve sits cranioventral to the aortic valve at the heart base. Here S2 is loudest. Distinguishing between these valves in cats and small dogs is difficult. S1 is loudest ventrocaudally at the cardiac apex. On the right, the tricuspid valve is heard at approximately the fourth intercostal space. The same principles apply in the cat, but heart sounds are often loudest over the sternum, as the chest cavity acts as a sounding board, like the body of a guitar, amplifying the sounds produced.

| Figure 1. The PMI of the various heart sounds in the dog. |

(A, aortic valve; M, mitral valve; P, pulmonary valve; T, tricuspid valve; IC4, fourth intercostal space). |

|

| |

Auscultation usually begins on the left with S2 around the third intercostal space (IC3) for the pulmonic valve and dorsally and caudally at IC4 for the aortic valve. Caudally and ventrally lies the mitral valve and, further caudally, listen as sounds diminish to avoid omission. On the right the tricuspid area is auscultated; the aortic and pulmonic valves may again be audible cranially and dorsally.

The lung fields are large areas on both sides of the thorax. Both sides are auscultated, starting over the heart base and moving cranially, caudally, dorsally and ventrally to cover the whole lung area on each side. Tracheal auscultation may allow differentiation of noise referred from the upper respiratory tract.

Abnormal Lung Sounds

There remains a lack of consistency in terminology, the recommended nomenclature stems from the American Thoracic Society Classification (Figure 2).

Examination includes counting respiratory rate and rhythm. Absence of sounds may indicate lung or lung lobe collapse, or the presence of fluid or masses in the pleural cavity.

Figure 2. Lung sound classification after the American Thoracic Society.

|

|

Produced in |

Cause |

Example |

Characteristics

(pitch/amplitude) |

|

Continuous sounds (inspiratory/expiratory) |

|

Wheeze |

Narrowed airways |

Airway secretions, airway flutter |

Asthma, bronchoconstriction |

High/variable |

|

Rhonchi |

Large airway with rapid air movement |

Large airway secretions |

Bronchitis |

Low/variable |

|

Stridor |

Upper airway

Inspiratory |

Turbulence/ obstruction |

Upper respiratory tract (URT) paralysis, foreign body |

High/variable |

|

Stertor |

Nasal/nasopharynx |

Airway narrowing/ obstruction |

Nasal foreign body, nasal tumour |

Variable/variable |

|

Discontinuous sounds (inspiratory only)--were 'rales' |

|

Crackles (fine) |

Re-opening small airways |

Fibrosis, lower airway disease |

Asthma

Westie lung |

High/low |

|

Crackles (coarse) |

Re-opening larger airways |

Obstruction, airway secretions |

Bronchitis |

Low/high |

Abnormal Heart Sounds

These consist primarily of arrhythmias, murmurs and gallop sounds. Some conditions cause muffling of the heart sounds, abnormal positioning of sounds and abnormal, displaced sounds, such as gut sounds in the thorax. Examination includes counting the rate and assessing the rhythm. Heart rates should be applicable to circumstances, considering the animal is in the surgery. Fast rates may be due to excitement, fear or pain, but also serious arrhythmia or to hyperthyroidism in cats. Slow rates may indicate athleticism, arrhythmia, hyperkalaemia or hypothyroidism in dogs. Anaesthetic agents produce changes in heart rate especially during prolonged anaesthesia. These require monitoring to assess whether they are expected or due to abnormalities. Heart sounds may be reduced or absent in the presence of pleural or pericardial effusion, or if mass lesions displace the heart.

Rhythm

When assessing the rhythm, is it regular or irregular, and if irregular, could it be a normal irregularity, such as sinus arrhythmia, or an abnormality? Sinus arrhythmia can be confused with pathological arrhythmia. If the heart is irregular, are there abnormal premature beats before the next expected beat? These are likely to be ectopic beats generated away from the natural pacemaker (the sinoatrial node). These are the arrhythmias most commonly heard through an oesophageal stethoscope. If the heart sounds like 'trainers in a tumble drier' (irregularly irregular), then suspect atrial fibrillation. Abnormally slow heart rates may indicate a conduction problem such as heart block, the pacemaker failing to produce ventricular contractions and an alternative 'escape' focus controlling the rhythm.

Murmurs

These are described in terms of intensity, PMI, timing in the cardiac cycle and character (Figure 3).

Figure 3. Intensity of murmurs.

|

Grade |

Description |

|

Grade 1 |

Very faint, observer needs to concentrate to hear it; may not be heard in all positions |

|

Grade 2 |

Quiet, but heard immediately after placing the stethoscope on the chest |

|

Grade 3 |

Moderately loud |

|

Grade 4 |

Loud, no palpable thrill |

|

Grade 5 |

Very loud, with thrill |

|

Grade 6 |

Very loud, with thrill. May be heard with stethoscope off the chest |

Timing

This describes the time in the cardiac cycle when the murmur occurs. Can be systolic (85%+ of small animal murmurs) occurring between S1 and S2 during ventricular contraction, diastolic between S2 and S1 during ventricular filling, or continuous occurring throughout the cycle. Murmurs can be 'early-', 'late-' or 'mid-' systolic or diastolic, whilst 'holo-systolic' refers to murmurs filling the gap between S1 and S2, and 'pan-systolic' from S1 through S2, obscuring the heart sounds.

Point of Maximal Intensity

The loudest point of a murmur normally correlates with the site of origin. Most commonly the left apex ('M' above) will identify a mitral murmur, the most commonly heard. The left basal murmur at 'P' or 'A' may be due to pulmonic or sub-aortic stenosis, whilst the continuous murmur at this site is often due to a patent ductus arteriosus (PDA). Right-sided murmurs at 'T' may be due to tricuspid regurgitation or a ventricular septel defect (VSD).

Character

Often difficult to appreciate, these characteristics may help to further define a murmur. 'Harsh' murmurs are associated with narrowings such as stenosis of a semilunar valve. Soft or 'blowing' murmurs are more typical of atrioventricular valve regurgitation.

Other Abnormal Heart Sounds

Gallop sounds, so called because they sound like a galloping horse, with three rather than two sounds accompanying each beat, are commonly heard in cats with cardiomyopathy. The additional sound is S3 or S4 (ventricular filling or atrial contraction) and may also occur in dogs with dilated cardiomyopathy.

References

1. Kvart C, Häggström J. Cardiac auscultation and phonocardiography in dogs, horses and cats. Uppsala, 2002 (self-published).

2. Smith FWK, Keene BW, et al. Rapid interpretation of heart and lung sounds: a guide to cardiac and respiratory auscultation in dogs and cats. Saunders, Philadelphia. 2006.