Abstract

The ultimate goal of an operant conditioning program is to create trust between animals and caregivers. The development of trust allows for a richer quality of life for both animals and zoo staff. Trust is built through clear communication, respect for individuals and their idiosyncrasies, and consistently positive experiences. As trust develops, animals become more relaxed, stress levels lessen, and animals display more normal social interactions. Immense health benefits are reaped from decreased daily stress levels and from the development of close and trusting social bonds. Lowered stress levels promote cardiovascular and metabolic health directly through decreased production and release of stress hormones.2 Improved social interaction leads to natural enrichment between troop members, and a cascade of other benefits. Trust allows the animals to display more natural behaviors, and allows for better observation of animals and interactions by staff. Improved evaluation of medical problems leads to more appropriate interventions and treatment, often without the need for chemical immobilization. Observation of more natural behaviors allows species managers to better understand life stages and social development of a species, which allows for improved management decisions at individual, troop, and population levels.

These dynamic changes were observed after initiation of an operant conditioning program with the bonobo troop in 1993. Prior to training, the bonobos were difficult to manage and exhibited hostile behaviors such as aggressively grabbing at and routinely urinating on care staff, spitting, screaming, and throwing feces. Medical care was complicated by the inability to separate animals and their fear of the veterinarians. The bonobos were distressed by novel situations and any variation in their routine induced intense panic and aggressive behaviors. The care staff often relied on trickery or bribery to manage the animals, which intensified their mistrust and fear. The staff elected to begin an operant conditioning program utilizing positive reinforcement in order to develop a safer working environment and a less stressful existence for the bonobos.

Keepers worked hard to establish safe, positive working relationships with the animals by rewarding desirable and non-aggressive behaviors. Undesirable behaviors were ignored and most were extinguished in 4–6 weeks. Initial concepts were simple and included name recognition, targeting, stationing, separations, and proper shifting. These early behaviors provided the necessary building blocks for more complex behaviors. Over the 2nd and 3rd year of the program, animals learned to present body parts for examination, the concept of left and right, and were desensitized to medical equipment such as syringes and stethoscopes. An early challenge of the program was to extend the trust that had built up between the animals and their keepers to the veterinary staff. Veterinarians and veterinary technicians visited the troop frequently and handed out treats in order to overcome the fear and negative history associated with past veterinary experiences. Keepers projected a strong positive attitude at the arrival of the veterinary staff in order to model a trusting behavior for the animals. In the same way, the bonobos were taught to accept unfamiliar people by introducing new people as often as possible. Acceptance of strangers is necessary for the successful use of medical consultants when needed.

After 3 years of consistent training, the level of trust between the bonobos and care staff increased, and the previous stress-related behaviors were markedly decreased. The bonobos demonstrated better listening skills, had more patience and did not become frustrated as easily. Most importantly, staff developed a deeper understanding of each animal’s personality and unique learning pattern. The bonobos evolved from animals that were fearful, guarded, and extremely dangerous into relaxed, interactive, inquisitive, caring, and gentle animals. The bonobos appear to enjoy their training intensely and become excited whenever they master a new behavior. Their intelligence and quick learning speed pushes the care staff to create a dynamic program that continues to stress more complex and multitask behaviors.

All behaviors are trained first by keepers. Once an animal is comfortable with a new behavior, the veterinary staff first observes, often suggesting variations that will be needed. Constant dialog is necessary between the veterinary staff and the keeper to develop functional behaviors. Next, veterinary staff participates in the behavior by shadowing the keeper movements. The keeper cues both the animal and the veterinary staff member during a behavior, with the animal focusing its attention on the keeper, even while the veterinarian or technician observes or touches it. In this fashion, the veterinarian can complete a fairly thorough physical examination, including ophthalmic, aural, and dental evaluations, thoracic auscultation, and mammary gland and lymph node palpation. Throat swabs, rectal cultures, and rectal temperatures are easily obtained.

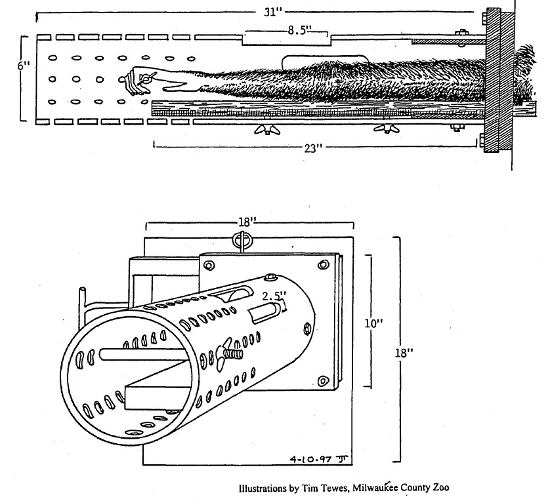

Blood collection is facilitated by a polyvinyl chloride (PVC) sleeve that attaches to the front wall of an animal holding area (Fig. 1). The bonobos place their arm inside the PVC sleeve, and grasp an adjustable bar at the far end. Veterinary technicians collect blood through slits cut into the wall of the sleeve on a regular basis from approximately half of the adult bonobos. While juveniles often mimic adult behavior and willingly place their arms in the blood sleeve, they rarely have the attention span, patience, and ability to hold still that is needed for successful venipuncture. Many bonobos also accept the placement of a blood pressure cuff on their arm while stationed in the blood collection sleeve. Radiographs of arms and legs of unanesthetized animals have been accomplished using this PVC sleeve, as have skin tests to screen for mycobacterial infections. Currently, cage modifications are underway to allow for thoracic or abdominal radiographs with animals positioned by operant conditioning.

| Figure 1 |

Illustration of “blood sleeve” used at Milwaukee County Zoo bonobo facility. |

|

| |

Cardiac and reproduction ultrasound examinations are performed in non-anesthetized animals stationed in an overhead chute of 5 × 5 cm metal mesh. The overhead chute connects two play areas and animals frequently relax in this chute. For ultrasonography, the bonobos assume sternal recumbency with their arms extended over their head. Animals with barrel-shaped chests must learn to twist onto the left hip in order to lower their left chest wall closer to the mesh for echocardiography. A 10 × 10 cm sliding door was designed to allow better access with the ultrasound probe but most measurements are taken with the probe inserted through the mesh. Initially, keepers acclimatized the animals to equipment below the chute by starting with an old black and white television and an extension cord attached to a syringe case.

The trust and training developed by this operant conditioning program has improved the level of veterinary care for the bonobos. Routine problems such as bite wounds can be evaluated thoroughly without the need for immobilization because the animals are quick to display their wounds to the keepers and veterinary staff, and allow minor wound cleaning with disinfectant solutions on a daily basis. Chronic medical conditions and the effects of therapy can be monitored over time through physical examination and sample collection. Species reference ranges for blood values, vital signs, cardiac parameters, fetal development, and gestational stages can be developed in awake, non-immobilized animals.

A major accomplishment of the operant condition program was a non-invasive artificial insemination that resulted in an offspring from a Species Survival Plan (SSP) recommended pairing. Bonobos show a preference towards mating with novel individuals,1 and an inhibition to breeding between individuals that have lived together for several years has been observed in several captive collections (Gay Reinartz, Bonobo SSP Coordinator, personal communication). In the wild, bonobos live in multimale, multifemale troops and this inhibition may represent a natural barrier to inbreeding. Two founder bonobos living at the Milwaukee County Zoo had reproduced naturally many times, but only one male offspring had survived to adulthood. While the SSP desired more offspring from this pair, no natural breeding had occurred between these individuals for several years. Through operant conditioning, the keeper was able to collect and test urine from the female to time ovulation, to collect an ejaculate from the male, and then insert the sperm coagulum deeply into the female’s vagina using a speculum. The female was then allowed to breed with sterile, vas clipped males to induce normal vaginal stimulation. The female tested urine-positive for pregnancy after 2 months, and paternity testing of the resultant offspring verified that the semen donor was the father.

In the spring of 2002, most of our eight male and eight female bonobos developed a severe respiratory infection shortly after a wave of respiratory illness passed through the local human population. Throat cultures of three bonobos also grew Streptococcus pneumonia, which can cause fatal pneumonia in this species. Daily medical evaluations of all animals and successful medication of extremely ill bonobos was only accomplished due to the advanced operant conditioning program. Sick animals needed to be shifted into safe groups to allow oral medication or darting as needed. Remarkably, the alpha male watched calmly while the veterinarians darted severely ill troop members, and even allowed immobilization of females for removal of infants with lobar pneumonia with a minimum of aggressive responses. Three infants were temporarily hospitalized for intensive care, then reunited with the troop 1 week later. The animals appear to recognize that interventions result in positive outcomes, and trust that troop members removed for medical care will return. Even after 2 weeks of intervention, the bonobos reacted positively to the presence of the veterinary staff.

The ongoing, dynamic operant conditioning program for the bonobo troop at the Milwaukee County Zoo has forever changed the way we care for our closest living relative. Our caregiving style is shaped by concern for both the physical and psychologic needs of the bonobo. The operant conditioning program has given the care staff much patience, empathy, humor, and a deep connection with the animals. The trust built by this program has allowed the animals to display far more natural behaviors and interactions than previously observed. The ability to manage the animals safely and with decreased stress has allowed for a significant increase in troop size to 16 animals. The larger troop size provides for more of the fission-fusion interactions normal to bonobo troops, and has allowed the care staff to understand natural behavior, social interaction, and developmental stages far more deeply. The increase in troop size and the operant conditioning program also allows for better collection of baseline medical data in this endangered species, which we hope will benefit bonobos in the wild and in captivity.

Acknowledgments

The operant conditioning program could not have been successful without the time and assistance of the entire keeper staff of the Stearns Family Apes of Africa and Primates of the World, veterinary technicians Margaret Michaels and Joan Maurer, previous veterinarian J. Andrew Teare, DVM, and training consultants Shelly Ballman of Oceans of Fun, Inc. and Beth Trczinko. The illustration was provided by Tim Tews, and has been previously published in the Bonobo SSP Husbandry Manual The Care and Management of Bonobos in Captive Environments” and in the conference proceedings from “The Apes: Challenges for the 21st Century,” Brookfield, IL, USA.

Literature Cited

1. Gold KC. Group formation in captive bonobos: Sex as a bonding strategy. The Apes: Challenges for the 21st Century Conf. Proc. (Brookfield, IL). 2001:90–93.

2. Sapolsky RM, Romero LM, Munck AU. How do glucocorticoids influence stress responses? Integrating permissive, suppressive, stimulatory, and preparative actions. Endocrine Rev. 2000;21:55–89.