Abstract

During an 11-year span (1994 to early 2005), Northwest ZooPath has received 1943 ferret biopsy or necropsy submissions. Since late 2003, a previously unrecognized disease process tentatively termed idiopathic polymyositis has been diagnosed in 13 ferrets at Northwest ZooPath.

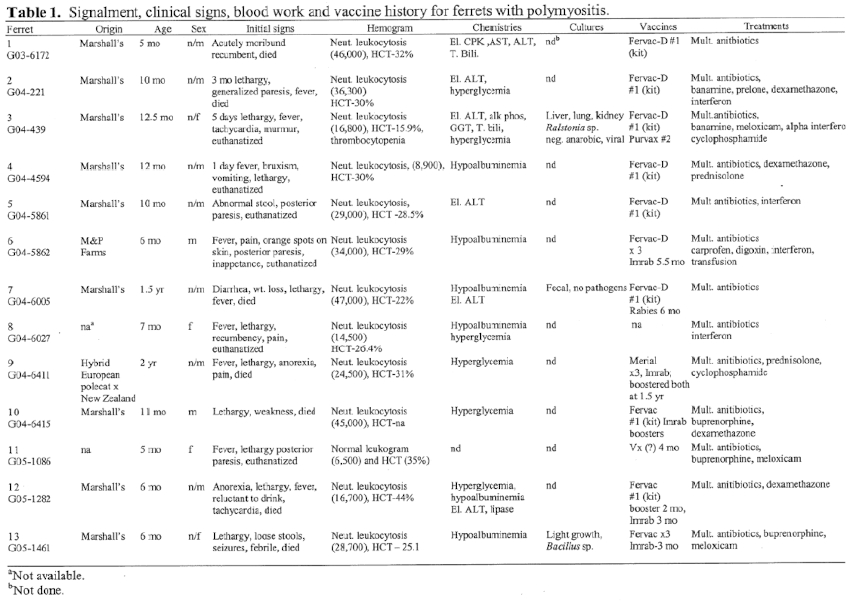

Signalment, clinical signs, blood work, and vaccine history for ferrets with polymyositis are summarized in Table 1. The ferrets ranged in age from 5–24 months of age and average age was 10 months. Nine were males, 4 females, and all but 1 male and 2 females were neutered. Clinical signs included high fever (10); lethargy (8); recumbency, ataxia, posterior paresis, or pain when moving (6); inappetence or anorexia (3); and abnormal stools (3). Blood work revealed mild to marked leukocytosis with mature neutrophilia (12), and mild to moderate, usually nonregenerative, anemia (11). Common serum abnormalities included mild to moderate elevation of ALT (6), mild hyperglycemia (6), and hypoalbuminemia (6). Treatment including various antibiotics, anti-inflammatories, glucocorticoids, antipyretics, pain killers, interferon, and cyclophosphamide, was ultimately unsuccessful in all cases and the patients either died (6) or were humanely euthanatized (7). Bacterial cultures of various tissues and feces from 3 animals revealed no pathogens.

Table 1

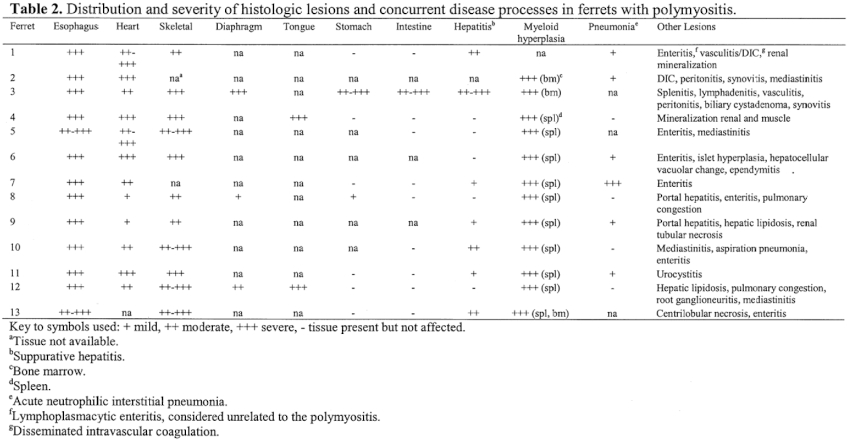

Distribution and severity of lesions are summarized in Table 2. Necropsy usually revealed no gross lesions; although, red and white mottling, dilatation of the esophagus, and white streaks in the heart, diaphragm, and intercostal muscles were seen in few ferrets. Histologic changes included moderate to severe suppurative to pyogranulomatous inflammation involving the skeletal muscle and blood vessels at multiple sites, particularly the esophagus (13), heart (12), and muscles of the hind limbs and lumbar region (11). Myeloid hyperplasia of spleen and/or bone marrow (12), hepatitis (6), pneumonia (6), and mediastinitis (4) were also prominent features. Cultures, electron microscopy, and protozoan immunohistochemistry conducted on some of these animals have been negative for infectious agents.

Table 2

The etiopathogenesis of polymyositis in ferrets is not known. It appears to be a disease of young ferrets characterized by rapid onset of clinical signs, high fever, neutrophilic leukocytosis, treatment failure, and death (or euthanasia). The distribution of histologic lesions, particularly in the esophagus, suggests that this is likely a single distinct entity. Culture data are incomplete, and the febrile nature of the disease, leukocytosis, and suppurative inflammatory features of the lesions suggest an infectious etiology, especially bacterial infection; however, the uniform failure of patients to respond to a broad variety of antibiotics, and the inability to detect bacteria in histologic sections suggests that bacterial infection is not likely. Various forms of vaccine-related polymyositis are seen in humans.1,2,4,5 Ferrets reportedly can develop vaccine reactions, but myositis was not described as an adverse effect.3 The vaccine history of the study animals is not consistent, and conclusions that incriminate vaccines cannot be drawn from these preliminary studies. Heritable immune mediated disease seems unlikely as affected ferrets are from different breeding facilities. Studies are underway to search for other infectious agents, and for other commonalities in affected animals that may provide clues as to the underlying cause.

Acknowledgments

The authors are grateful to the following for submission of cases: Brantley and Jordan Animal Hospital, Macon, GA; Ocean State Veterinary Specialists, East Greenwich, RI; Somers Animal Hospital, Somers, NY; Essex Animal Hospital, Bloomfield, NJ; Midwest Bird and Exotic Animal Hospital, Westchester, IL; Rutherford Animal Hospital, Rutherford, NJ; Affordable Pet Clinic, Nampa, ID; All Pet Complex, Boise, ID; South Wilton Veterinary Clinic, Wilton, CT; Bird and Exotic Pet Hospital, Midvale, UT; Tennessee Valley Veterinary Clinic, Tuscumbia, AL.

Literature Cited

1. Cotterill, J.A., and H. Shapiro. 1978. Dermatomyositis after immunization. Lancet. 2:1158–1159.

2. Ehrengut, W. 1978. Dermatomyositis and vaccination. Lancet. 1:1040–1040.

3. Greenacre, C.B. 2003. Incidence of adverse events in ferrets vaccinated with distemper or rabies vaccine: 143 cases (1995–2001). J Am Vet Med Assoc. 223:663–665.

4. Hanissian, A.S., A.J. Martinez, J.T. Jabbour, and D.A. Duenas. 1973. Vasculitis and myositis secondary to rubella vaccination. Arch Neurol. 28:202–204.

5. Winkelmann, R.K. 1982. Influenza vaccine and dermatomyositis. Lancet. 2:495.