Veterinary Procedures Facilitated by Behavioral Conditioning and Desensitization in Reticulated Giraffe (Giraffa camelopardalis) and Nile Hippopotamus (Hippopotamus amphibius)

Introduction

Medical and diagnostic procedures can be challenging with exotic species. The large species are especially challenging due to the infeasibility of physical restraint for most contact procedures.

Historically, procedures on large or dangerous exotic species necessitated immobilization or general anesthesia. This produces inherent risks with altered physiology, recumbency, and trauma during induction and recovery. The use of narcotics is common in these instances. These agents pose additional risks to the user of these drugs. Renarcotization and even death can be subsequent results of large animal chemical immobilizations.

Animal behavioral conditioning and desensitization techniques have been employed for years on domestic animals. More recently these techniques have been incorporated into several animal programs in zoos worldwide. These techniques have been used with a wide variety of species from birds to elephants.1,4,7 The most well-known methods used involve marine mammals (T. Lacinek personal communication).3

At Busch Gardens in Tampa, FL many areas of the zoo department are employing techniques of conditioning and desensitization to decrease the need for immobilizations especially in high-risk animals.2 These include giraffe, black rhinoceros (Diceros bicornis),6 and Nile hippopotamus5,8. The focus of this presentation will be on giraffe and hippopotamus.

Giraffe

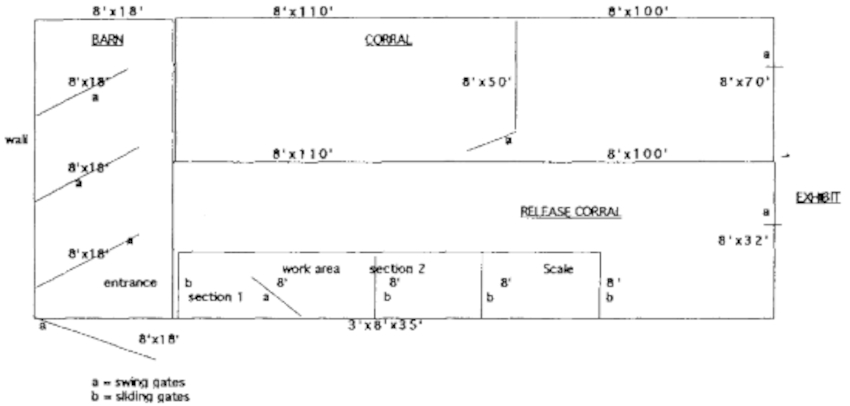

A corral and chute system was constructed to facilitate working giraffes as a herd for elective procedures. The procedures include vaccinations, injectable deworming, tuberculosis testing, and phlebotomy. Body weights were also recorded with the use of a platform scale built into the last section of the four-section chute.

The corral and chute system was designed in three parts (Figure 1). The first is a corral that is used to hold the group of animals to be worked through the chute. When possible, the animals are held in this area overnight to let them acclimate and calm down prior to moving them individually through the chute. This helps greatly to minimize excitement and potential trauma during the chuting episode. This also helps cut down on time. A group of 12 animals can be worked in under 2 hours once they are familiar with the system and it becomes a regular routine.

Figure 1. Giraffe coral, barn, and chute

The second area is a smaller semi-enclosed barn adjacent to the chute. This area has a series of large gates that can be closed behind the animal as it advances into the next part of this area. This serves to confine the giraffe into a smaller and smaller area until it can eventually be encouraged through the entrance to the chute.

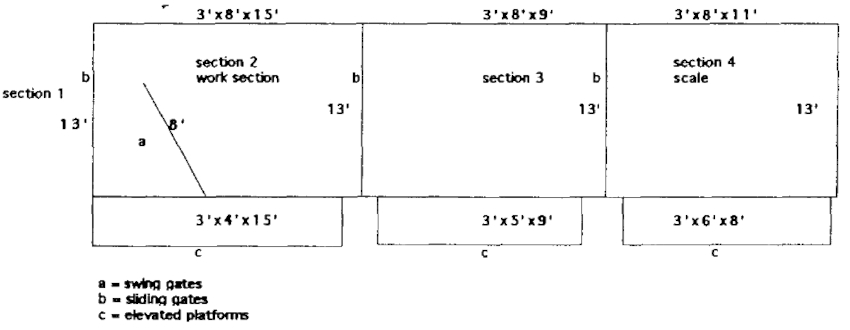

The animal then must enter the chute (Figure 2) in order to advance out of the small area where it is eventually confined. It advances to the front of the first of three sections where a split swing gate is closed and secured behind the animal to prevent it from backing up. The animal is worked in this area. Once it is calm, the door in front of it is opened and it advances into the second area. The giraffe is allowed to calm down to prevent bolting through the last door. Then it is allowed to advance into the third compartment where it is weighed on an electronic scale. Once a weight is recorded and the animal is fairly calm, it is released into an adjacent coral that is opened to the exhibit enclosure.

Figure 2. Giraffe chute

Conditioning these animals to a chute has also facilitated anesthetic procedures. The chute is confining enough to allow for more control during the induction and recovery phases of the procedure.

Hippopotamus

Two of the five (2.3) Nile hippopotamuses currently residing at the park have been maintained in an exclusively outdoor sand and water enclosure (Figure 3) for over 34 years. For many of those years these two female Nile hippopotamuses have been conditioned to approach a fence when they saw a keeper with a white bucket approach. A white, 5-gallon bucket was used to carry their grain and fruit at mealtimes. Even when the times varied, these animals remembered the significance of the white bucket.

We decided to make use of this simple conditioned behavior to allow medical and diagnostic procedures to be performed on these high anesthetic risk animals. The hippos were initially taught to approach a specific place along the fence to receive hand feeding of grain and fruit from the bucket. Mouth opening and closing was taught to occur on cue and reinforced with food.

The next step was to build a makeshift stanchion along the fence line. The animal was worked and conditioned in this area while being fed. In this stanchion, we were able to perform minor diagnostic procedures such as ultrasonography, punch biopsies of a perineal mass, and bacterial culture.

When this conditioning was consistent, a temporary stanchion was constructed along the fence with a head and tail gate (Figures 4.1 and 4.2). The hippos were conditioned to stand in the structure for longer periods of time each day. Occasionally, manipulation of the animals would occur to desensitize them to various veterinary procedures. In this system, we were able to perform a more extensive biopsy of a perineal mass and explore the region with the use of topical and local anesthesia.

In the future, a more permanent structure is to be constructed in the animals’ enclosure. Work in this structure is to be a routine for both hippos. Desensitization of various body areas is to be incorporated into this routine to facilitate medical or diagnostic procedures while avoiding the high risk of general anesthesia or immobilization in this species.

A recently constructed house was constructed for 2.1 unrelated hippopotamuses. A chute has been built into the aisle way that provides access to and from the exhibit. The animals must routinely pass through this chute at least twice daily. Soon they will be conditioned to stay in the chute for a period of time with the gates closed. Gradually they will receive similar conditioning as the older females in the pond exhibit. This will facilitate achieving the goal of having all hippos in the park conditioned to be handled for routine medical and diagnostic procedures without anesthesia or sedation.

Summary

Through the use of conditioning and desensitization two high anesthetic risk species have been able to be handled for routine veterinary care on a regular basis. This facilitates safe handling of valuable animals as well as provides more opportunities to add to normal data on these species in zoos worldwide. Conditioning in this way has also allowed close examination of animals that develop health problems without the need for anesthetic agents. As the use of these techniques becomes more widespread, the availability of more biologic and anatomic parameters in a greater variety of species will facilitate the management and preservation of endangered and threatened animals in captivity.

VIN editor: Some images not available at time of publication.

Literature Cited

1. Bloomsmith, M. 1992. Chimpanzee training and behavioral research: a symbiotic relationship. In: Proc Am Assoc Zoo Parks Aquariums/Canadian Assoc Zoo Parks Aquariums. 403–408.

2. Bush, M. 1993. Anesthesia of high-risk animals: giraffe. In: Fowler, M.E. ed. Zoo and Wild Animal Medicine. 545–547.

3. Dover, L., Fish, L., Turner, T., Kelley, A. 1994. Husbandry training as a technique for behavioral enrichment in marine mammals. In: Proc Am Assoc Zoo Vet. 284.

4. Kinzley, C. 1993. Restraint facilities and operant conditioning in large land mammals. In: Proc Am Assoc Zoo Parks Aquariums Regional Conf. 97–101.

5. Krueger, S., Shellabarger, W., Reichard, T. 1996. Hippopotamus training: implications for veterinary care. In: Proc Am Assoc Zoo Vet. 54–58.

6. Michel, A., Illig, M. 1995. Training as a tool for routine collection of blood from a black rhinoceros (Diceros bicornis). An Keeper’s Forum. 22:294–299.

7. Phillips, M., Grandin, T., Graffam, W., Irlbeck, N.A., Cambre, R.C. 1998. Crate conditioning of bongo (Tragelaphus eurycerus) for veterinary and husbandry procedures at the Denver Zoological Gardens. Zoo Biology. 17:25–32.

8. Reichard, T., Shellabarger, W., Laule, G. 1992. Training for husbandry and medical purposes. In: Proc Am Assoc Zoo Parks Aquariums. 396–402.