Y. Bruchim

Senior Lecturer of Veterinary Medicine, The Hebrew University of Jerusalem, Jerusalem, Israel

The use of ultrasound has developed over the past 50 years as an indispensable first-line diagnostic tool for traumatic patients and cardiac/respiratory evaluation of symptomatic patients. AFAST focused examination of four sites in the abdomen designed to evaluate presence of free abdominal fluid, while TFAST is used to detect the presence of air or fluid in the pleural and pericardial space. The Blue VET (bedside lung evaluation) was developed in as emergency lung ultrasound to detect interstitial-alveolar lung injury.

AFAST—Abdominal Focused Assessment with Sonography for Trauma

There are 2 applications of AFAST in dogs experiencing abdominal trauma:

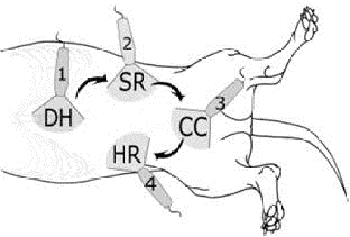

1. AFAST-focused examination of four sites in the abdomen designed to quickly (5 minutes) to rule in or rule out the presence of free abdominal fluid (typically indicative of hemorrhage) in 4 quadrants of the abdomen (Figure 1). FAST examinations are very sensitive and specific for detection of free abdominal fluid, even when performed by non-radiologists, but are less sensitive at detecting intra-abdominal injury following penetrating trauma than following blunt trauma (Boyen, Rozanski JAVMA 2004).

2. Serial AFAST (Lisciandro et al. JVECC 2009)—Serial AFAST examinations was designed to detect changes in the quantity of fluid present in the abdomen over time, especially when combined with determination of abdominal fluid score (AFS). Serial AFAST examinations should be performed every 2–4 hours, or more frequently as dictated by clinical findings. Some dogs with negative results on the initial AFAST examination had positive findings on serial AFAST examinations.

Abdominal fluid score—semiquantitative evaluation of the degree of free fluid (typically hemorrhage) performed by recording the number of sites among the four standard views. Animals with an AFS of 0, 1, 2, 3, and 4 would show negative findings at all sites, positive results at one site, positive findings at any two sites, positive results at any three sites, and positive findings at all four sites, respectively. The study indicate that AFS of 3&4 is associated with higher risk of anemia, blood transfusion and increased alanine aminotransferase (PCV<25%) (Lisciandro et al. JVECC 2009).

How to Perform AFAST Technique?

Free fluid tends to accumulate in the most dependent areas of the abdomen. The examination can be completed without clipping and application of alcohol. Can be performed in right or left lateral recumbency. To detect fluid in the abdomen, ultrasonographic views (transverse and longitudinal) are obtained at each of 4 sites; just caudal to the xiphoid process, on the midline over the urinary bladder, and at the left and right flank regions (Figure 1). The examiner may choose right lateral if volume status of the patient is to be evaluated ultrasonography or if the left retroperitoneal space is to be evaluated. Left lateral recumbency may be preferred if right retroperitoneal space is to be evaluated. The transducer is centered at one of four locations and then moved at least 4 cm and fanned through at least 45 degrees in a cranial, caudal, left, and right direction. The examination can be accomplished using only the longitudinal view at each site, although adding the transverse view is helpful if results of the longitudinal view are equivocal.

The four sites are:

1. Diaphragmatico-hepatic (DH): just caudal to the xiphoid. Can also evaluate the thoracic cavity (pleural and pericardial cavities)

2. Cysto-colic (CC): midline site over the bladder

3. Hepato-renal (HR): right flank site

4. Spleno-renal (SR): left flank site

| Figure 1 |

|

|

| |

TFAST-Thoracic Focused Assessment with Sonography for Trauma

TFAST are designed to RI/RO the presence of air or fluid in the pleural space, and RI/RO the presence of fluid in the pericardial space. In the normal lung movement of the pleural line on each other create the normal Glide sign indicating a normal apposition of the lung against the thoracic wall: a dynamic finding. It may be intermittent with low respiratory rates or apnea. When the gliding is lacking and and there is step sign it may be indicative to the presence of air in the pleural space.

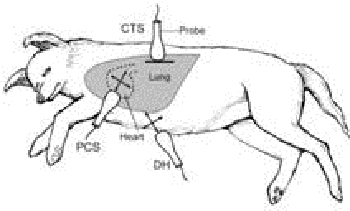

| Figure 2 |

|

|

| |

Lisciandro et al. JVECC 2008 showed that TFAST has 78% sensitivity and 93% specificity for detecting pneumothorax. In contrast to AFAST this technique need more experienced (non-radiologist) emergency doctor. In that study there were considerable differences in sensitivity when performed by an experienced sonographer (95% sensitivity with >70 scans) compared with a unexperienced sonographer (45% sensitivity with <15 scans). “Gliding sign” should be detected in order to diagnose pneumothorax. Despite variation, the negative predicative value of the TFAST examination is high, which indicates that the presence of the glide sign essentially rules out pneumothorax. However, failure to detect a glide sign may result from conditions other than pneumothorax.

TFAST Technique

TFAST can be performed in left, right, or sternal recumbency, and involves five views:

1. Chest tube site [CTS] view—one on each side of the thorax in longitudinal plane perpendicular (horizontally) to the ribs in the dorsal third, between the 7–9 intercostal spaces. Used to confirm or rule out pneumothorax. The sonographer must keep the transducer immobile on the chest wall to maximize the chance of detecting the glide sign.

2. Pericardial chest site [PCS] view—one on each side of the chest in the longitudinal and transverse planes, with movement and fanning of the transducer, between the 5–6 intercostal spaces.

3. Diaphragmatico-hepatic view of AFAST.

In the normal lung there will so called the alligator sign or Bat sign: The pleural-pulmonary interface (PP line) is the roughly horizontal white line running between the two ribs and is usually visible just distal to the ribs (with exception of subcutaneous emphysema).

Lung point: The severity of pneumothorax can be evaluated by moving the probe in a dorsal to ventral direction. The point at which the glide sign returns is known as the lung point in which the step sign will be presented. This is a very specific finding and confirms the presence of pneumothorax. In the case of massive pneumothorax a lung point will not be detected.

Step sign: glide sign deviates from its normal continuity. Suggests thoracic trauma, or in non-trauma patients, lung consolidation/masses.

So in general we can say that:

- Pneumothorax is ruled out if a glide sign and/or B-lines are detected.

- Pneumothorax is strongly suspected when glide sign and B-lines are absent.

- Pneumothorax is definitively confirmed if lung point is identified.

Emergency Lung Ultrasound to Detect Interstitial-Alveolar Lung Injury

BLUE (bedside lung evaluation): the key concept in this setting is the detection of B-lines that originate from the pleural line. The proximity and number or density of B-lines correlate with extravascular lung water, and the anatomic location of B-lines with respect to lung anatomy correlates with different pathologic lung conditions.

Emergency lung ultrasound may add a particular niche in differentiating underlying causes of respiratory distress in the severely dyspneic patient that is in too unstable a condition to allow thoracic radiography.

Vet Blue is performed from both sides of the chest wall with 4 points in each side.

- Caudodorsal lung view (Cd) similar to the CTS view in TFAST

- Perihilar lung region (Ph)—caudodorsal 6–7 intercostal space

- Middle lung lobe (Md)—at 4–5 intercostal space

- Cranial lung region (Cr)—3–4 intercostal space.

What signs and lines we can see in VET BLUE:

A-lines: a result of reverberation artifact causes the pleural line to be replicated in the sonographic far field. The distance between subsequent A-lines corresponds to the same distance between the skin surface and the parietal pleura. A-lines should be seen in the normal lungs, but also may be seen in patients with pneumothorax. A-lines should not be confused with the pleural line.

B-lines: (ring-down/comet tail/lung rockets) are reverberation artifacts originating from the visceral pleura lines appear as hyperechoic vertical lines extending from the pleural line to the edge of the far field image, passing through A-lines without fading. B-lines move in a to-and-fro fashion (pendulum) with inspiration and expiration, and are synchronous with the glide sign. An occasional B-line is considered normal; excessive B-lines are indicative of interstitial-alveolar lung abnormality. When B-lines are numerous they called a B-pattern.

Lung curtain—the lung artifact created by movement of the lungs at the costophrenic angles creates a vertical sliding artifact similar to the opening and closing of a theater curtain, which should not be confused with the glide sign. The ultrasound probe should be moved cranially if the curtain sign is noted.

Summary

A glide sign with A lines (horizontal lines) is considered a normal lung or “Dry Lung” only to be confounded with the pneumothorax (dry lung with absent glide sign). When B lines or so called lung rockets are presented the lung will be defined as “Wet Lung” meaning parenchyma lung abnormality (e.g., lung edema, contusion and bleeding, pulmonary masses, lung infiltration).

Here are some examples from Liscando et al.

(VIN editor: examples not available.)