Department of Clinical Sciences, Faculty of Veterinary Medicine, University of Montreal, Saint-Hyacinthe, QC, Canada

Sustained release systems include any drug delivery system that achieves slow release of drug over an extended period of time (hours and/or days) in a controlled manner. Such systems provide "hands-off" analgesia, minimize systemic side effects and drug accumulation, reduce fluctuations in drug plasma concentrations and may not require infusion devices. Long-sustained release formulations of opioid drugs have been shown to provide longer release kinetics, fewer undesirable side effects, and in some cases superior efficacy compared with standard formulations of the same opioid. There has been some evidence that these formulations may be a promising technique to relief of long-term acute pain.1 A topical eutectic mixture of lidocaine and prilocaine or a liposome-encapsulated formulation of lidocaine can be applied to the skin after shaving and prior to catheterization and/or venous puncture in dogs, cats and small mammals, in order to provide analgesia.2 Absorption of local anesthetic occurs but they are usually below the toxic doses. In this lecture, the application of intraperitoneal analgesia, incisional and intratesticular blocks are discussed as potential "analgesic tools" as well as other loco-regional anesthetic techniques.

Transdermal patches (fentanyl, lidocaine and buprenorphine) are adhesive patches that are placed on the skin to deliver a specific dose of drug through the skin and into the plasma. The patch provides a controlled release of the drug through a rate-limiting porous membrane with a drug reservoir. These patches are usually available in different sizes based on the delivery rate to the systemic circulation across the skin. The recommended location for patch placement includes the dorsal or lateral thorax, or dorsal neck. The onset and duration of action vary according to the drug in use and species, but it can be up to 12–24 h and 72 h, respectively. There may be large individual variability in analgesic plasma concentrations and efficacy. Fentanyl patches have been extensively evaluated in the veterinary literature. This opioid has shown great potential for postoperative analgesia in dogs, but some limitations in the cat due to individual variability and erratic/unpredictable pharmacokinetics (PK).3 Further studies are warranted to identify the analgesic effects of lidocaine and buprenorphine patches in dogs and cats.4 The PK of lidocaine patches have been determined in dogs and cats.5

Drugs such as fentanyl, morphine, remifentanil, lidocaine, ketamine and/or dexmedetomidine have been used in clinical anesthesia in order to provide better cardiovascular stability by reducing inhalant agent requirements.6 In addition, the combination of these drugs with different pharmacologic mechanisms may provide profound analgesia and even greater inhalant-sparing effect in animals undergoing surgery. Wound "soaker" catheters are flexible indwelling catheters that are imbedded near or in surgical sites that can be used to deliver continuous or intermittent infusions of local anesthetics for postoperative pain management. These catheters have been used in dogs and cats after major surgery. Although there are very few reports in veterinary medicine about the efficacy of pain management with these catheters, a recent retrospective study showed that the incidence of complications is low7 and the amount of rescue analgesics is considerably less in treated dogs versus non-treated dogs.8 This technique is becoming more popular as a pain management adjuvant.

This lecture discusses different, practical and cost-effective approaches to pain management in the clinical setting.

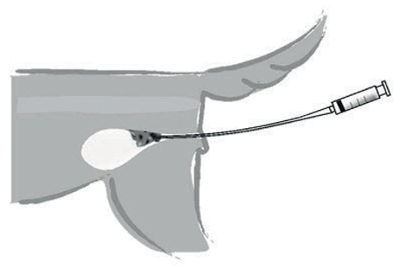

| Figure 1. The catheter is inserted in the mass in the urinary bladder. |

|

|

| |

References

1. Krugner-Higby L, Smith L, Schmidt B, et al. Experimental pharmacodynamics and analgesic efficacy of liposome-encapsulated hydromorphone in dogs. J Am Anim Hosp Assoc. 2011;47:185–195.

2. Wagner KA, Gibbon KJ, Strom TL, et al. Adverse effects of EMLA (lidocaine/prilocaine) cream and efficacy for the placement of jugular catheters in hospitalized cats. J Feline Med Surg. 2006;8:141–144.

3. Hofmeister EH, Egger CM. Transdermal fentanyl patches in small animals. J Am Anim Hosp Assoc. 2004;40:468–478.

4. Murrell JC, Robertson SA, Taylor PM, et al. Use of a transdermal matrix patch of buprenorphine in cats: preliminary pharmacokinetic and pharmacodynamic data. Vet Rec. 2007;28:578–583.

5. Weiland L, Croubels S, Baert K, et al. Pharmacokinetics of a lidocaine patch 5% in dogs. J Vet Med A Physiol Pathol Clin Med. 2006;53:34–39.

6. Steagall PV, Teixeira Neto FJ, Minto BW, et al. Evaluation of the isoflurane-sparing effects of lidocaine and fentanyl during surgery in dogs. J Am Vet Med Assoc. 2006;229:522–527.

7. Abelson AL, McCobb EC, Shaw S, et al. Use of wound soaker catheters for the administration of local anesthetic for post-operative analgesia: 56 cases. Vet Anaesth Analg. 2009;36:597–602.

8. Hardie EM, Lascelles BD, Meuten T, et al. Evaluation of intermittent infusion of bupivacaine into surgical wounds of dogs postoperatively. Vet J. 2011;190:287–289.