The Role of Non-Governmental Organizations in Assisting Zoos and Aquaria During Disasters

Abstract

Although there is still controversy about climate change, reports and research describe the probability of an increase in the severity and intensity of extreme weather events (severe storms, droughts, flooding). The frequency and intensity of violent events such as tornadoes or hurricanes will become more difficult to reliably predict. Zoos and aquariums may find themselves in situations where these intense weather events may place their animals in jeopardy and therefore must be moved or require the assistance from volunteers to aid with injured or displaced animals. One source of trained volunteers could be found within non-governmental organizations (NGOs) that have experience working with wild animals through various research programs. NGOs that have assisted with the collection of physiological data from wild marine mammals (dolphins, manatee, and seals) are an untapped source of volunteers who have hundreds of hours of valuable experience in handling and caring for wild species. Also, because these wild animals must often be sedated for the collection of data, these volunteers also have experience with anesthesia and the care of sedated wild animals. For example, a collaborative effort has been ongoing for 6 y between the United States Geological Survey (USGS) and the authors’ NGO (Oceanographic Environmental Research Society—OERS) where volunteers have been sent to assist with the capture/care of wild manatees for the collection of samples/data. The benefits of initiating collaborative efforts between an NGO and a zoo or aquarium would create a huge resource of experienced volunteers during times of disaster or crisis.

Introduction

There still much controversy about climate change and possible effects. However, it would seem that there is credible climate change research describing the probability of increasing numbers of extreme weather events (large storms, droughts, floods, etc.) that will be more severe and of higher intensity.9,11 As well, the frequency and intensity of violent events such as tornadoes or hurricanes will become more difficult to reliably predict.9 It has also been reported that regional geographical differences such as being near mountains, located on a river, or situated along the coast may place more cities at risk, as it is harder to predict extreme weather events within these smaller areas.3,9,11 This was clearly seen during Hurricane Katrina where some areas were either totally devastated due to a storm surge or affected by high winds (Figures 1,2).

Figure 1. House destroyed by storm surge

Figure 2. Tree stripped bare by high winds

Most of the earth’s population lives along some coastal region and as a result, eight of the world’s largest cities can be affected by earthquakes, and six of the world’s largest cities are vulnerable to storm surge and tsunami waves.4 In the United States, depending on the criteria used to describe coastal counties, population numbers living on or near a coastal zone varies between 37% to 49%.3 Most zoos and aquariums are built near the larger population centers (e.g., Aquarium of the Americas in New Orleans) or in disaster-prone areas (e.g., Monterey Bay Aquarium, California). Therefore, they are also at a higher risk of being affected by some sort of natural disaster or strong storm-like event.

Unfortunately, since many zoos or aquariums are located within or near these large, populated areas, they find themselves in situations where these intense weather events may place their animals and facility in jeopardy (Figure 3). This may require moving some of their animals to areas of safety or even relocation as was seen with the Aquarium of the Americas in New Orleans during and following Hurricane Katrina in 2005 when they had to relocate their entire penguin colony to the Monterey Bay Aquarium in California.9 The New York Aquarium was seriously affected when Hurricane Sandy devastated the facility with over $65 million in damage. It took 7 months for it to re-open and required the dedicated aquarium staff to work courageously to save every animal in their care except for 150 freshwater koi.8

Figure 3. A facility destroyed by storm surge

Zoos, Aquariums and Disaster Planning

In December 2012, the United States Department of Agriculture Animal and Plant Health Inspection Service announced that all licensed and registered facilities must have an emergency plan in place to better protect their animals during times of disaster.10 The Zoological Best Practices Working Group for Disaster Preparedness and Contingency Planning (ZBPWG) has written an excellent guide to assist the various groups who care for and deal with wildlife which includes zoos and aquariums.13 It is a very complete guide for facilities of any size, individuals, or professional associations within the United States. However, it is only a guide, and the mission statement of the ZBPWG is to “promote a culture of ‘all hazards contingency planning and preparedness’ for the managed wildlife community.” To that end, the group will research, prepare, review and disseminate documents to assist facilities in drafting their own contingency plans. The Working Group will encourage facilities to work with first responders, local emergency management and other stakeholders to draft useful plans that are integrated into their jurisdictional emergency management infrastructure.”14 It leaves the details of the emergency plans to each facility or individual which are based on several factors or the resources available including the size of the facility, number of animals involved, and number of staff. The ZBPWG advises assembling a planning team comprised of stakeholders, experts and partners which could include key non-governmental organizations (NGOs) such as American Association of Zoo Veterinarians (AAZV), Association of Zoos and Aquariums (AZA), American Association of Zoo Keepers (AAZK), and many others. The AAZV has organized a Disaster Preparedness Committee which supports its members to prepare for disasters through education, developing of disaster/response templates, web resources, a frequently asked questions (FAQ) sheet for veterinarians and disaster response, and initiating contact with several agencies.1

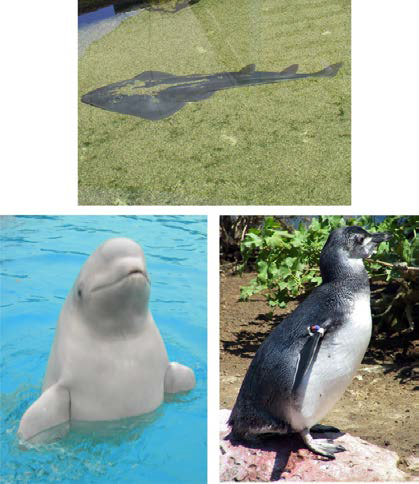

As far back as 2003, the AAZV has published several papers in their proceedings or had posters presented at their annual meeting to address topics such as a veterinarian’s role during a disaster or disaster planning for zoos or aquariums. In 2003 and 2008, Dr Mark Lloyd published papers describing the role of zoological veterinarians in various emergency scenarios and the need for an integrated national plan for zoos and aquariums to help mitigate the pain and suffering of their animals.6-7 Wittnich and Belanger (2009) presented their study of how unprepared Canadian zoos and aquariums were, and found that 6 out of 13 facilities did not have an emergency plan in place.13 That same year, Dr. Lisa Done reviewed the need for zoos and aquariums to be prepared for disasters and the specific concerns and considerations of the many species (fish, avian, mammals) found within facilities4 (Figure 4). However, there has been no mention in any plans or presentations of using NGOs during times of disaster. NGOs have at their disposal an excellent pool of trained volunteers who have experience in the handling and caring for wildlife while assisting with research in the wild.

Figure 4. A wide variety of species are located in zoos or aquariums that require care after a disaster

NGOs and Disasters

Following any type of disaster or emergency, there is a knee-jerk reaction on the part of the authorities to close off outside volunteer assistance until Incident Command has been firmly established. This was seen with Hurricane Katrina and the BP Gulf of Mexico oil spill where the response to assist with the care of pets or the rehabilitation of wildlife was controlled by authorities which allowed very few outside NGOs or volunteers to assist.12 The lack of volunteer assistance might put enormous stress on the regular staff members who, during times of a disaster, will spend huge amounts of time performing life-saving daily activities to keep the animals alive, which was seen at the New York Aquarium after Hurricane Sandy.8 Therefore, it is critical that zoos and aquariums develop a disaster response plan that includes NGO volunteers that they can call upon to assist. However, it is often very difficult to find qualified and trained volunteers who have experience with wildlife species found in a zoo or aquarium, and it is very expensive and time consuming to train them. One source of trained volunteers could be found within NGOs that have volunteer members who have hands-on experience working with wild animals through various research programs. These NGOs have worked alongside scientists, biologists, and veterinarians assisting with the collection of physiological data from wild marine mammals (dolphins, manatee, and seals). These volunteers have hundreds of hours of valuable experience in handling and caring for wild species, often sedated, while collecting data.

A collaborative effort has been ongoing for 6 y (2008–2013) between the USGS, Florida Fish and Wildlife Conservation Commission, and our NGO, the Oceanographic Environmental Research Society (OERS), where volunteers have been trained to assist with the capture and care of wild manatees during the collection of samples and data for health assessment programs (Figures 5,6). The collaboration between these various groups includes biologists, scientists, wildlife veterinarians, veterinary technicians, and NGO volunteers who are trained as teams for the collection of data to understand the health status of a large species of marine mammal—the manatee (Trichechus manatus)H. The manatee is a large marine mammal weighing up to 800 kilograms and has a total length of up to 335 centimeters.2 This means that although a docile animal, the manatee may become very difficult and dangerous to handle if the team members are not properly trained or understand the anatomy, physiology, or behavior of this unique marine mammal species. Therefore, the training and coordination of a large number of volunteers and the organizing of the logistics behind each capture is crucial in ensuring both the safety of the animals and every team member. Between 2008 to 2012 the authors’ NGO group has sent teams of volunteers to assist with the capture and handling of over 100 wild manatee.

Figure 5. Volunteers from the Oceanographic Environmental Research Society, a non-governmental organization, assisting with the capture of a wild manatee

Figure 6. Veterinarians and veterinary technicians working alongside Oceanographic Environmental Research Society volunteers

During times of a disaster, collaborative efforts between an NGO and a zoo or aquarium would have far reaching benefits towards the safety and care of the facility animals. It is obvious that an NGO that has been assisting a zoo or aquarium with its research program would offer a huge source of trained and experienced volunteers. During a disaster, these volunteers could assist with many of the daily chores and husbandry duties (e.g., preparing food, feeding, or cleaning of pools). These volunteers would also ensure that essential equipment such as pumps and generators are filled with fuel or maintenance of that equipment is kept going day and night to make sure that no animals suffer or die when electrical power is not available. This would free up more experienced staff or management to do other critical responsibilities. An NGO may have volunteer veterinarians and veterinary technicians who are trained with many hours of handling wildlife and could now become part of the disaster planning efforts and response. Training could be shared between both the wildlife facility and the NGO during research efforts thereby making it easier to have volunteers who are prepared to respond. As well, having an NGO who is already part of the facility’s research programs and is included within its disaster planning and response efforts would ensure a compatibility of ethics towards the efforts of conservation of captive and wildlife species.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to recognize the Oceanographic Environmental Research Society (OERS) for permission to reproduce all of the figures.

Literature Cited

1. American Association of Zoo Veterinarians. 2012. Disaster Preparedness Committee. http://www.aazv.org/displaycommon.cfm?an=1&subarticlenbr=854. (Accessed May 18, 2013) (VIN editor: This link was not accessible as of 12-22-20.)

2. Bonde, R. K., A. Garrett, M.P. Belanger, N. Askin, L. Tan, and C. Wittnich. 2012. Biomedical health assessments of the Florida manatee in Crystal River-providing opportunities for training during the capture, handling, and processing of this endangered aquatic mammal. Journal of Marine Animals and Their Environment. 5(2):17–28.

3. Crowell, M., K. Coulton, C. Johnson, J. Westcott, D. Bellomo, S. Edelman, and E. Hirsch. 2010. An estimate of the U. S. population living in 100-year coastal flood hazard areas. Journal of Coastal Research. 26(2):201–211.

4. Done, L.B. 2009. The wild side of disaster: Planning to protect captive wildlife facilities. Proc. Am. Assoc. Zoo Vet., Amer. Assoc. Wildl. Vet. Joint Conf. Pp. 147–152.

5. Government Office for Science. 2012. Foresight Reducing Risks of Future Disasters: Priorities for Decision Makers. Final Project Report. The Government Office for Science, London. Pp. 34.

6. Lloyd, M., B. Kellogg, and S. Zeeve. 2003. A veterinarian’s role in a disaster: getting involved at a national level. Proc. Am. Assoc. Zoo Vet. Pp. 111–115.

7. Lloyd, M. 2008. An integrated national plan for zoos and aquariums in disasters. Proc. Am. Assoc. Zoo Vet., Assoc. Rep. Amph. Vet. Annu. Conf. Pp. 73–74.

8. Stepansky, J, and G. Adams. 2013. New York Aquarium on Coney Island, swamped by Hurricane Sandy, to reopen May 25. New York Daily News. www.nydailynews.com/new-york/brooklyn/new-york-aquarium-coney-island-set-reopen. (Accessed May 15, 2013.)

9. Sauerbom, R., and K. Ebi. 2012. Climate change and natural disasters—integrating science and practice to protect health. Glob Health Action. 5: 192–195. https://doi.org/10.3402/gha.v5i0.19295. (Accessed May 12, 2013) (VIN editor: The link was modified on 12-22-20).

10. United States Department of Agriculture. 2012. USDA Publishes Final Rule to Help Facilities Be Better Prepared for Emergencies. www.aphis.usda.gov/aphis/ourfocus/animalwelfare/SA_Animal_Welfare_News/CT_USDA_Publishes_Final_Rule_to_Help_Facilities_Be_Better_Prepared_for_Emergencies. (Accessed May 15, 2013). (VIN editor: The link was modified on 12-22-20.)

11. Van Aalst, M.K. 2006. The impacts of climate change on the risk of natural disasters. Disasters. 30(10): 5–18.

12. Wittnich, C., and M.P. Belanger. 2008. How is animal welfare addressed in Canada’s emergency response plans? J. Appl. Anim. Welfare Sci. 11:125–132.

13. Wittnich, C., and M.P. Belanger. 2009. Disaster planning for zoos and aquaria: How far have we come or should we go? Proc. Am. Assoc. Zoo Vet., Amer. Assoc. Wildl. Vet. Joint Conf. Pp. 135.

14. Zoo Best Practices Working Group for Disaster Preparedness and Contingency Planning. 2011. Zoological Best Practices Working Group Planning Roadmap—A Basic Guide for Emergency Planners for Managed Wildlife Facilities. Pp. 1–32.