Abstract

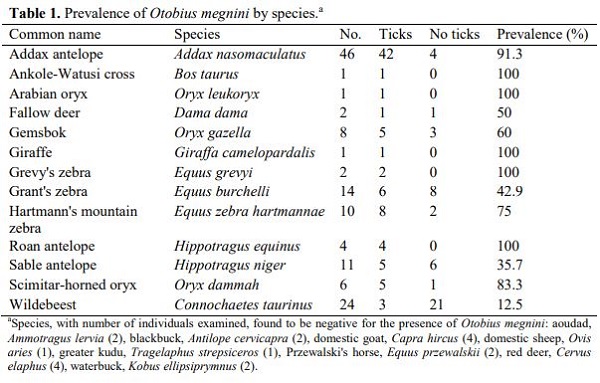

Spinose ear tick (Otobius megnini) infections of ungulates at Fossil Rim Wildlife Center (FRWC) are commonly seen. This one-host soft tick (Acari: Argasidae) is native to southwestern United States and Mexico. Larval and nymphal ticks are parasitic, often feeding deep in the ear canal. The adults, however, do not feed. Final molt and reproduction occur off the host. This tick has not been reported to transmit pathogens,2 and in domestic animals morbidity may be limited to irritation, secondary infections and potential impacts on production.1,3,4 From October 2009 through March 2012, ear ticks were found in 13 of 21 ungulate species and 84 of 148 individuals examined (Table 1). Infected ears were treated with ivermectin paste (Vetrimec Paste 1.87%, Vet One, Meridian, ID 83680 USA) applied in the ear canal after manual removal of ticks. Adult and larval ticks have been collected at FRWC from animal sheds and in the natural environment near sheds. Adult ticks were most often found in the crevices behind beams, the base of posts, and debris under ledges, and were collected most successfully with a debris-filtering technique. Larvae were successfully collected using carbon dioxide traps. Current research is underway to further document spatial and temporal distribution; this data will be used to better manage tick populations off the host by altering the environment at the most advantageous times and locations. Off host treatment will likely prove essential in controlling tick populations due to limited handling of FRWC ungulates.

Literature Cited

1. Chigerwe, M., J.R. Middleton, I. Pardo, G.C. Johnson, and J. Peters. 2005. Spinose ear ticks and brain abscessation in alpaca (Lama pacos). J. Camel Pract. Res. 12:145–147.

2. Jellison, W.L., E.J. Bell, R.J. Huebner, R.R. Parker, and H.H. Welsh. 1948. Q fever studies in southern california: IV. Occurrence of Coxiella burneti in the spinose ear tick, Otobius megnini. Public Health Rep. (1896–1970). 63:1483–1489.

3. Madigan, J.E., S.J. Valberg, C. Ragle, and J.L. Moody. 1995. Muscle spasms associated with ear tick (Otobius megnini) infestations in five horses. J. Am. Vet. Med. Assoc. 207:74–6.

4. Strickland, R.K, R.R. Gerrish, and J.L. Hourrigan. 1976. Ticks of Veterinary Importance. Animal and Plant Health Inspection Service, U.S. Dept. of Agriculture, Washington, DC. 51–52.