Measurement of Glomerular Filtration Rate, Renal Plasma Flow and Endogenous Creatinine Clearance in Cheetahs (Acinonyx jubatus jubatus)

Abstract

Glomerular filtration rate (GFR), renal plasma flow (RPF) and the creatinine clearance rate (CCR) were determined in 12 captive cheetahs (seven females and five males ranging in age from 1.5 to 7.5 years; mean 5±2.5 years) during general anesthesia with Telazol® and isoflurane by measuring the urinary clearances of inulin, para-aminohippuric acid (PAH), and endogenous creatinine (CCr), respectively. The GFR and the RPF were stable during the procedure, with mean values of 1.59±0.17 ml/min/kg body weight for GFR and 5.12±1.15 ml/min/kg body weight for RPF. While the mean value for CCr of 1.47±0.20 ml/min/kg body weight was significantly (p<0.05) less than the corresponding value for GFR, the mean difference between GFR and CCr was only 0.11±0.02 ml/min/kg and the CCr was highly correlated with GFR (R2=0.928; p<0.0001). The measurement of CCr in cheetahs should provide a reliable estimate of GFR, facilitating the early detection of renal disease in this species.

Introduction

Renal disease is a leading cause of mortality and morbidity in captive cheetahs.5 The genetic homogeneity of these animals may predispose them to diseases such as renal amyloidosis and glomerulosclerosis that ultimately cause their death.1,5,6,8 Unfortunately, efforts to characterize and control these diseases are hampered by the fact that they are often only confirmed on postmortem examination.1,8 Early detection of renal disease in captive cheetahs may allow the development of a program to screen these animals, characterize the natural progression of the disease(s), study interventions, and introduce appropriate management techniques. This study evaluated methods to determine glomerular filtration rate (GFR), renal plasma flow (RPF) and endogenous creatinine clearance (CCr) in captive cheetahs, and to determine the relationship between GFR and CCr in this species.

Methods

Urinary clearances were measured in 12 captive cheetahs from White Oak Conservation Center: seven females and five males ranging in age from 1.5 to 7.5 years (mean 5±2.5 years). All cheetahs had been previously diagnosed with lymphoplasmacytic gastritis by histologic examination of gastric biopsies. Helicobacter spp. were present in gastric biopsies of five of the cheetahs. Animals were immobilized with tiletamine and zolazepam (Telazol®, Fort Dodge, Fort Dodge, IA, USA; 3.4±0.5 mg/kg IM), intubated, and maintained with isoflurane (Abbott Laboratories, North Chicago, IL, USA) in oxygen. Subcutaneous administration of inulin (Sigma Chemical Co., St. Louis, MO, USA; 220 mg/kg) and PAH (Sigma Chemical Co., St. Louis, MO, USA; 8.25 mg/kg) occurred at t=0, and was repeated at t=25 min. A urinary catheter was aseptically placed for initial urine collection at t=0, with 2–3 additional 30-minute collection periods starting after t=50. Blood was collected for serum at t=0 and t=50 min. Inulin and PAH concentrations in urine and plasma were determined by anthrone reaction methodology.2,3 Creatinine concentration in urine and serum were determined by a semi-automated method (Spectrum CCX, Abbott Diagnostics, Irving, TX, USA).

The glomerular filtration rate (GFR), renal plasma flow (RPF), and CCr were expressed as urinary clearance of inulin, PAH and endogenous creatinine, respectively. Clearances were calculated as ml/min/kg body weight by using the standard clearance formula: (urine concentration of substance × urine volume)/(plasma concentration of substance × duration of period × body weight in kg). For each animal, the mean of the clearance determinations for the two or three periods was taken to represent the value for clearance for that animal. Linear regression analysis was used to evaluate the nature of the relationship between GFR and CCr (Statview 4.5, Abacus, Berkeley, CA, USA).

Results

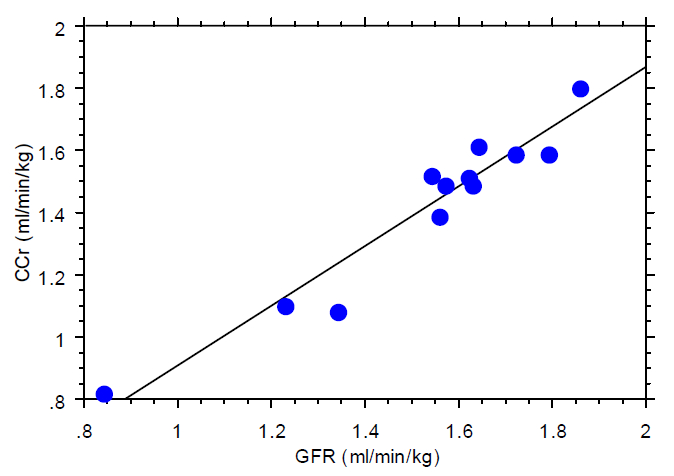

Urinary clearance values and associated parameters are listed in Table 1. The GFR and RPF were stable during the procedure, with mean values (ml/min/kg body weight) of 1.59±0.17 for GFR and 5.12±1.15 for RPF. The mean value for GFR was significantly greater than the corresponding value for CCr (p<0.05), with a mean difference of 0.11±0.02 ml/min/kg body wt and the ratio CCr/GFR was significantly (p<0.05) less than 1.00. GFR and CCr were highly correlated (Figure 1), with an R2 value of 0.928 (p<0.0001).

Table 1. Urinary clearance values obtained in 12 captive cheetahs

|

Parameter

|

Mean ± standard deviation

|

|

GFR (ml/min/kg body wt)

|

1.59±0.17

|

|

RPF (ml/min/kg body wt)

|

5.12±1.15

|

|

CCr (ml/min/kg body wt)

|

1.47±0.20

|

|

CCr/GFR

|

0.93±0.05

|

Figure 1. Relation between urinary clearance of inulin (GFR) and endogenous creatinine (CCr) in 12 captive cheetahs

Although the mean value for GFR (1.59±0.17 ml/min/kg body weight) was significantly greater than the corresponding value for CCr (1.47±0.20 ml/min/kg body weight), the mean difference of 0.11±0.02 ml/min/kg was small, and the two clearance determinations were highly correlated with an R2 value of 0.928 (p<0.0001).

Discussion

Early detection of renal insufficiency is necessary to characterize and control renal disease in captive cheetahs. In this study, urinary clearance of inulin and PAH were assessed as measures of GFR and RPF, and the reliability of urinary clearance of endogenous creatinine was evaluated as an estimate of GFR in this species. GFR and endogenous creatinine clearance were well correlated in this study. In domestic cats, there has been controversy surrounding the correlation of inulin and endogenous creatinine clearance,4,7,9,10 primarily because of the presence of non-creatinine chromogens which confounds the procedure technically. In captive cheetahs, the strong relation and small difference between CCr and GFR support the use of endogenous creatinine clearance as a measure of renal function, possibly because non-creatinine chromogens comprise a relatively small fraction of the total measured SCr in cheetahs. The use of CCr to estimate GFR simplifies the procedure, as endogenous creatinine clearance is less technically challenging than GFR determination using inulin. Endogenous creatinine does not require injections or specialized laboratory assays and might prove to be an appropriate addition to routine health screening in captive animals. The correlation between CCr and GFR provides a rationale for testing additional animals to further evaluate CCr as an early indicator of renal disease in captive cheetahs.

Acknowledgments

We appreciate the cooperation and assistance of Dr. Scott Citino and the staff of White Oak Conservation Center. Invaluable support and funding also provided by Dr. Scott A. Brown and staff of the Department of Physiology & Pharmacology, College of Veterinary Medicine, University of Georgia, Athens, GA, USA.

Literature Cited

1. Bolton, L.A., and L. Munson. 1999. Glomerulosclerosis in captive cheetahs (Acinonyx jubatus). Vet. Pathol. 36: 14–22.

2. Brown, S.A. and C.A. Brown. 1995. Single-nephron adaptations to partial renal ablation in cats. Am. J. Physiol. 269: R1002–R1008.

3. Brown, S.A., C. Haberman, and D.R. Finco. 1996. Use of plasma clearance of inulin for estimating glomerular filtration rate in cats. Am. J. Vet. Res. 57: 1702–1705.

4. Finco, D.R., and J.A. Barsanti. 1982. Mechanism of urinary excretion of creatinine by the cat. Am. J. Vet. Res. 43: 2207–2209.

5. Munson, L. 1993. Diseases of captive cheetahs (Acinonyx jubatus): Results of the Cheetah Research Council pathology survey 1989–1992. Zoo Biol. 12: 105–124.

6. O’Brien, S.J., M.E. Roelke, L. Maker, A. Newman, C.A. Winkler, D. Meltzer, L. Colly, J.F. Evermann, M. Bush, and D.E. Wildt. 1985. Genetic basis for species vulnerability in the cheetah. Sci. 227: 1428–1434.

7. Osbaldiston, G.W., and W. Fuhrman. 1970. The clearance of creatinine, inulin, para-aminohippurate and phensulphthalein in the cat. Can. J. Comp. Med. 34: 138–141.

8. Papendick, R.E., L. Munson, T.D. O’Brien, and K.H. Johnson. 1997. Systemic amyloidosis in captive cheetahs. Vet. Pathol. 34: 549–556.

9. Rogers, K.S., A. Komkov, S.A. Brown, G.E. Lees, D. Hightower, and E.A. Russo. 1991. Comparison of four methods of estimating glomerular filtration rate in cats. Am. J. Vet. Res. 52: 961–964.

10. Ross, L.A., and D.R. Finco. 1981. Relationship of selected clinical renal function tests to glomerular filtration rate and renal blood flow in cats. Am J Vet Res. 42: 1704–1710.