B. Doneley

Avian and Exotic Pet Medicine, The University of Queensland, Gatton, QLD, Australia

Abstract

Parrot chicks are altricial, i.e., totally dependent on their parents (or hand rearer) for warmth, food and psychological development. This paper explores the normal development of psittacine chicks and the factors that impact this development. Understanding this development leads the clinician to a better understanding of the impact of disease (and its treatment) on these chicks.

Normal Development

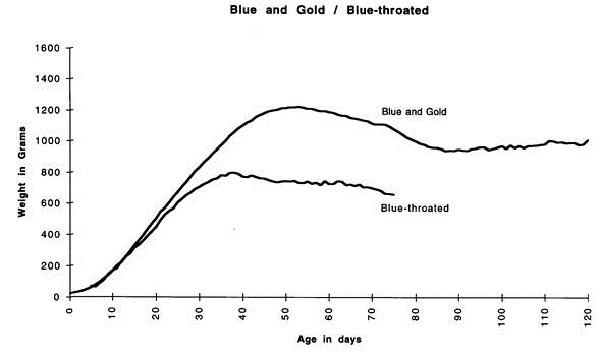

Chicks grow at a rapid rate until they begin to wean, at which time they peak their weight and then lose weight until they reach their adult weight and plateau. The weight and age will vary between species but the growth rate, expressed as a chart (see Figure 1) remains similar.

Prior to full feathering the normal chick’s skin should be pink or pink-yellow in colour, and soft and warm to the touch. Depending on the species, some chicks are hatched naked or with down feathers, which may be white, yellow or grey in colour. A second wave of down feather growth begins at 1–3 weeks of age and, sometimes, even later in some species.

Pin feathers begin to emerge at 2–3 weeks of age. The body contour feathers emerge over the shoulders first; the pattern of emergence after that varies between species, although usually the body contour feathers emerge at the same time or shortly before the secondary flight feathers on the wings. Primaries may begin to develop before secondary feathers, but usually mature after them. Final feather maturity is usually not complete before the bird has weaned.

The eyes begin to open at 10–28 days and take several days to open completely. Most Australian and African parrots hatch with their ears open. The ears of Eclectus and South American species should be open within 2–3 weeks after hatching.

The normal crop should have some food in it at most times. It should not be over-distended, nor should it have significant amounts of air or gas in it. Rhythmic contractions of the crop should be visible in neonatal chicks, and the crop should nearly empty in 4–6 hours in all chicks.

In neonatal chicks the abdomen should be large and convex relative to the rest of the body. The liver may be visible through the skin in very young chicks, and rhythmic contractions of the ventriculus should be visible. The duodenal loop may be visible. There should not be bruising or haemorrhage visible. As the chick grows, the abdomen reduces in size relative to the rest of the body.

Pre-weaning chicks should be either resting, sleeping or calling for food. As they get older, the chicks still spend a lot of time sleeping, but are more interested in their environment and in socializing with nursery mates. A feeding response (vigorous extension and bobbing of the head and neck) should be easily elicited by pressing gently at the commissures of the beak.

Hand Rearing

Hand rearing can be done for several reasons: to increase production from rare or valuable species; when the chick is orphaned; or in an attempt to make a better socialised chick. Recent studies suggest that the latter is not always achieved by hand rearing, but many aviculturists maintain that hand reared chicks make better pets.

The timing of commencement of hand rearing varies between the owner and the individual circumstances. Some chicks, artificially incubated, are reared from the time of hatch; others are left with their parents for 2–3 weeks and are ‘pulled’ for hand rearing just before their eyes open, while others are taken just before fledging and are then reared until ready to wean.

The frequency of feeding is dependent on the age of the chick:

1. Hatch to 1 week - every 2 hours

2. 1 week to 3 weeks - every 4 hours

3. 3 weeks to 6 weeks - every 6–8 hours

4. 6 weeks to weaning - every 8–12 hours

A variety of quality commercial diets are available today and it is uncommon to see ‘homemade’ recipes. The volume fed is between 8-12% of the chick’s bodyweight. The food should be mixed fresh for each feed and fed at approximately 41°C (normal body temperature for birds).

Weaning is a stressful time for both the chick and the hand rearer. The chicks will often start to refuse feeds and may regurgitate part of what is been offered, A good selection of a wide variety of foods should be available for the chicks at this time - formulated diets, vegetables and fruit - and intake of these foods monitored carefully.

Health Determinants

As most companion birds are altricial (i.e., totally dependent on their parents or rearer and the environment), their health status is determined not only by their current environment, but also by the ‘input’ from their parents and how the eggs were incubated. We can divide these factors into three broad groups (see Table 1).

Table 1. Determinants of health for chicks

|

Pre-laying factors

|

Parental genetics become a major issue in the breeding of mutations, where closely related birds are mated to develop certain characteristics such as colour. Unfortunately, along with desirable characteristics such as new colour, undesirable physical characteristics, such as decreased body size or physical deformities, can also occur.

|

|

The maturity of the parents will affect the size of the eggs laid, the immunity passed through the egg, and the number of eggs laid.

|

|

The health of the parent birds can affect the chick via pathogens transmitted through the egg to the chick, and by the degree of transference on maternal immunity via the albumen and yolk.

|

|

The diet fed to the parents, particularly the levels of calcium and vitamins, will have a direct effect on the vitality, development and health of chicks - even before hatch.

|

|

Incubation factors

|

Artificial vs. natural incubation: as a general rule parent-incubated eggs tend to hatch out stronger chicks. Advances in incubation techniques are, by and large, resulting in better chicks. However, skill and experience are required to match the results seen in natural incubation.

|

|

Temperature, humidity and hygiene in the nest box or incubator will have direct effects on the development of the chick and its hatchability and strength after hatch.

|

|

Care in handling of the eggs by either the parents or the incubator operator, as well as the frequency and degree of rotation during artificial incubation, can affect the degree of difficulty in hatching, as well as an effect on the incidence of malpositions.

|

|

Post-hatch factors

|

Temperature extremes can force the chick to divert resources from its growth and health towards maintaining a constant body temperature. Humidity extremes can predispose a chick to dehydration, respiratory infections and skin problems (e.g., toe constriction).

|

|

Poor hygiene will substantially increase the concentration of pathogens (or potential pathogens) in the chick’s environment. With the chick’s immune system still developing, this creates a high probability of infectious disease.

|

|

Although the era of homemade hand-rearing diets is passing, nutrition of the chick is still a major factor in the health of the chick. The practice of adding ingredients to a well-balanced formula (often based on anecdotal information from other aviculturists) can have major detrimental effects on the chick.

|

|

Management of the nursery, in particular biosecurity and the quarantine of new chicks from different sources, will determine the likelihood of introduction of infectious diseases such as avian polyomavirus.

|

Detailed knowledge of hand-rearing practices, including weaning ages, can be obtained from reputable aviculture literature.

Examination of the Chick

History

As with any other medical case, a good history of the chick is an essential key in the diagnostic workup. Factors to consider stem from the earlier discussion on determinants of a chick’s health. They include:

- The parents - Their genetics, diet, maturity and health status.

- Incubation - Was it artificial or natural? The hatchability of fertile eggs is a key indicator of incubation performance, and hopefully it can be found in the aviculturist’s records.

- Hatching: If the eggs were artificially incubated, were there any problems with hatch?

- How is the nursery managed regarding hygiene, biosecurity, and the source of eggs and/or chicks?

- What type of food is been fed, how is it prepared, what volume is fed and how frequently?

- If there are any siblings or other chicks, have there been any problems or deaths within the group?

- What records does the aviculturist keep? Details on hatch dates, hatch weights, growth rates, mortalities, medications, and previous medical problems are valuable sources of information, but are sadly lacking in many cases.

Physical Examination

Weight

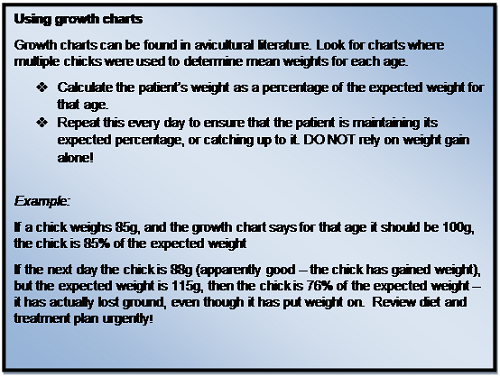

The chick should be weighed and its weight compared with the expected weight for that age, found in growth charts (if available). All chicks will gain weight each day it is the rate of weight gain that is more important than the actual weight. This can be monitored by expressing the chick’s weight as a percentage of the expected weight for that age. If a problem exists, improvement can be seen as a gain in percentage of expected weight, rather than actual weight gain. (Figure 2)

Posture

It is important to be aware that chicks sleep and rest in what seems to be ‘awkward’ positions. (For example, conure and macaw chicks often sleep on their on their backs.) These positions change as the chick moves; one should look for postures that do not change with movement.

Conformation

The positioning and conformation of the limbs and the spine should be checked. Common conformational abnormalities include a kinked (or ‘wry’) neck, scoliosis, kyphosis, tibiotarsal or femoral rotation, and anteroflexion of the toes.

Body Condition

The toes and elbows in a well-nourished, healthy chick should be ‘plump’. Thin toes and elbows are a good indicator in neonatal chicks of dehydration, malnourishment or disease. Palpation of the pectoral muscles is helpful; the soft keel bone at this age should be well fleshed with soft (but poorly developed) pectoral muscles.

Behaviour

Restlessness could indicate incorrect environmental temperature or stress (e.g., excessive lighting). Failure to elicit a feeding response can be an indication of disease, hypothermia or weakness.

Skin

Pallor of the skin can indicate hypothermia, anaemia or illness. Erythematous skin can indicate hyperthermia or illness. Heavily wrinkled skin indicates dehydration.

Crop

The normal crop should have some food in it at most times. It should not be over-distended, nor should it have significant amounts of air or gas in it. Rhythmic contractions of the crop should be visible in neonatal chicks, and the crop should nearly empty in 4–6 hours in all chicks.

Head

The size of the head should not be excessively large in relation to body size. The beak should have a normal conformation. There should be no sinus swellings. The nares should be open and symmetrical.

The eyes should be symmetrical and healthy in appearance. They begin to open at 10–28 days and take several days to open completely. Most Australian and African parrots hatch with their ears open. The ears of Eclectus and South American species should be open within 2–3 weeks after hatching.

Oral Cavity

The oral cavity should be examined for diphtheritic plaques or other abnormalities. Its colour should be noted; it is normally pale pink.

Abdomen

There should not be bruising or haemorrhage visible. The abdomen can be trans-illuminated with an intense focal light for closer inspection. As the chick grows, the abdomen reduces in size relative to the rest of the body. It should be concave when palpated; a convex abdomen could indicate a degree of abdominal distension.

Feather Growth

Abnormalities include:

- Feathers erupting in an unusual pattern (e.g., in a circular pattern on the crown of the head, rather than running parallel along the line of the body).

- Stress bars in the opened vane.

- Abnormal colouring.

- Haemorrhage in the calamus.

- Dystrophic development.

Droppings

The faecal portion should be relatively well formed, light brown in colour, and not malodorous. A degree of polyuria is normal (especially in hand-reared chicks), but this should lessen as the chick ages. Excessive or persistent polyuria warrants further investigation.

Diagnostic Testing

Microbiology is an important tool in assessing gastrointestinal flora. Gram stains and cultures are frequently used to assess crop or other gastrointestinal problems. Normal bacterial flora includes Lactobacillus, Streptococcus, Staphylococcus and Bacillus spp. Low numbers of E. coli are often normally cultured as well. Other gram-negative bacilli and Candida are rarely cultured from healthy chicks.

Clinical pathology can be used readily on chicks. It is important to note that compared to adults of the same species, chicks normally have:

- Lower PCV and higher white cell count

- Lower total protein and uric acid

- Higher CK

Radiography is an essential tool for assessing the status of the skeletal system, but the low density of the bones and the cartilaginous growth plates in very young chicks can make this difficult.

Common Problems

Crop Stasis (‘Sour Crop’)

This is a commonly seen problem in paediatric medicine, with most sick chicks having varying degrees of crop stasis. All too often hand rearers attempt to diagnose and treat this problem without seeking to understand the underlying pathology.

Aetiology

Causes include:

- Generalized ileus (e.g., systemic illness, foreign bodies, chilling, heavy metal toxicosis, dehydration).

- Crop disorders (e.g., foreign bodies, overstretched/ atonic crop, infectious ingluvitis, fibrous food impaction, or crop burns).

- Dietary problems (e.g., cold food, excessively watery food, food that settles out in the crop, overfeeding, overly dry food).

Clinical Presentation

Signs include the crop failing to empty in more than six hours, regurgitation and loss of feeding response. Most chicks will be dehydrated on presentation (erythematous wrinkled skin, tenting of the skin and sunken eyes).

Aspiration of the crop contents usually reveals the sour-smelling fermenting ingesta (‘sour crop’) or thickened ingesta (hand-rearing formula with the fluid drawn out of it).

Faecal output may be reduced, and the stool may be unformed or pasty.

Diagnosis

This is based on crop and faecal cytology (Gram stain) and culture, haematology and biochemistry, and radiography.

Management

The cause should be identified using the means outlined above, and corrected where possible.

The crop should be emptied with a feeding tube and repeatedly lavaged with warm saline until a clear wash has been obtained. (In some extreme cases, e.g., foreign bodies, it may be necessary to perform an ingluviotomy.) It should always be assumed that these chicks are dehydrated, and they should be treated with parental fluids until crop motility has been restored.

Appropriate antimicrobials should be given as indicated by crop and faecal cytology/culture. It is overly simplistic to assume that these cases are always yeast infections; in the author’s experience bacterial overgrowth is usually more common.

A crop ‘bra’ can be used if needed. This is a non-adhesive bandage placed under the crop and around the wings to ‘lift and support’ the atonic crop in order to allow gravity to assist with crop emptying.

Once the crop has been emptied, in many cases it may be advisable to leave it empty for a few hours while dehydration is corrected. Initial feeds should be of small volumes of isotonic saline. If this moves through, solids can be added. Small, watery meals should be fed often. Pre-digesting the hand-rearing formula with a small amount of pancreatic enzymes can liquefy the diet without diluting it.

Motility modifiers (e.g., metoclopramide or cisapride) may assist in restoring motility, although their efficacy is poor if used without other supportive measures. Metoclopramide, in particular, is usually ineffective unless given as a constant rate infusion. In uncomplicated cases (where the chick is otherwise bright), a strong solution of fennel tea given by crop drench may assist in restoring motility.

The prognosis is good, provided prompt and appropriate therapy is provided.

Stunting

This is a common condition where chicks in the first 30 days of life do not grow normally and become stunted.

Aetiology

It is usually associated with improper feeding techniques (poorly balanced or incorrectly mixed diets, inadequate amounts fed, etc.), poor environmental conditions (temperature and humidity extremes) or disease (e.g., renal disease).

Clinical Presentation

Signs include subnormal weight gain, reduced muscle mass (toes, wings, back should be checked), abnormal feathering (e.g., head feathers develop in a circular pattern on the crown) and oversized head relative to the size of the body. Eyelids fail to open normally or when expected, and there is delayed ear opening or narrowing of the ear canal. The affected bird may suffer with chronic, recurrent infections, and be constantly calling and begging for food. As the chick gets older it often develops a globose head with an elongated slender beak. The eyes may appear exophthalmic because of the misshapen skull.

Management

The predisposing cause should be identified and treated. Nutritional inadequacies should be corrected. The prognosis is good if the problem is diagnosed early and treated successfully.

Infectious Disease

Infectious diseases are quite common in young chicks; their low level of immuno-competence combined with often substandard rearing practices leaves them highly predisposed to infection. This same lack of immuno- competence means that the progression of an infectious disease in young birds is often rapid. Prompt and aggressive therapy is needed to save the patient.

Aetiology

Infections may be bacterial (Pseudomonas, E. coli, other gram-negative bacteria); fungal (Candida, Aspergillus); viral (polyomavirus, adenovirus, PBFD); Chlamydia psittaci; parasitic: protozoa (Cryptosporidia, Trichomonas, Cochlosoma, Coccidia and Atoxoplasma [in young canaries]); and nematodes (ascarids, Capillaria and Acuaria).

Clinical Presentation

Signs include lethargy, loss of feeding response, pallor or erythema of the skin, dehydration, crop stasis, vomiting/regurgitation, weight loss or failure to thrive, subcutaneous haemorrhage, feathering abnormalities and sudden death.

Management

The aetiological agent should be identified and the chick treated accordingly. The patient will require supportive care.

Research

1. Abramson J, Speer B, Thomsen J (1996) The Large Macaws: Their Care, Breeding, and Conservation. Raintree Publications.

2. Clubb SL (1997) Psittacine pediatric husbandry and medicine. In: Avian Medicine and Surgery. RB Altman, SL Clubb, GM Dorrestein, K Quesenberry (eds). WB Saunders, Philadelphia, pp. 73–95.

3. Flammer K, Clubb SL (1994) Neonatology. In: Avian Medicine: Principles and Application. BW Ritchie, GJ Harrison, LR Harrison (eds). Wingers Publishing, Lake Worth, pp. 805–841.

4. LaBonde J (2006) Avian reproductive and pediatric disorders. In: Proceedings of the Annual Conference of the Association of Avian Veterinarians Australian Committee, pp. 229–238.

5. Schubot RM, Clubb KJ, Clubb SL (1992) Psittacine Aviculture: Perspectives, Techniques and Research. Avicultural Breeding and Research Center, Loxahatchee, FL.