L. Findji

Enterotomies and enterectomies are most often simple procedures, which can, however, have devastating consequences if not performed properly, as septic peritonitis invariably results from intestinal wound dehiscence. This text assumes that the reader has a basic knowledge of these techniques, which will not be reviewed. It only focuses on a few points which should help maximise efficiency and improve outcomes in small intestinal surgery.

Be Atraumatic

The pursuit of the unreachable goal of atraumatic surgery is common to all surgical procedures. Respecting tissues and leaving them as healthy as possible is the main key to success. Briefly, it consists of handling tissues delicately (which includes keeping them moist), preserving their vascularisation and limiting their bacterial contamination. Respecting the vascularisation is paramount in the success of the procedure. Any excessive exteriorisation of the intestines impairs its blood flow and should be avoided. Similarly, care must be taken not to compress the jejunal arteries and veins during the procedure.

Using atraumatic means of temporarily occluding the intestinal lumen is also critical, whether it be non traumatic Doyen forceps or the assistant surgeon's fingers.

Isolate the Surgical Field

Entero- and enterectomies involve opening a contaminated hollow viscus. The surgical field must therefore be isolated from the rest of the abdominal cavity as much as possible to limit bacterial contamination. However, unless it is massive and unaddressed, bacterial contamination is not a limiting factor in the success of intestinal surgery.

When the procedure involves a portion of intestine that can easily be exteriorised, which is the case of the greatest part of the jejunum and ileum, an efficient way to isolate it is to use a fenestrated impervious paper drape through which the intestinal loops of interest are passed. Fenestrated, moist laparotomy swabs can be used on both sides of the drape to help keep tissues moist. Once the septic step of the procedure is over, the exposed intestines and intestinal wound are copiously rinsed over this additional drape, which is then removed with the moist laparotomy swabs. Instruments and gloves are either rinsed or changed, depending on the degree of contamination, and surgery can proceed routinely.

Enterotomy Tips

Biopsies of the small intestine should be small, so that no reduction of the intestinal lumen results from it, but include all layers of the intestinal wall. To achieve these goals, a useful tip is to pass a suture through the intestinal wall on its antimesenteric border. Gentle vertical traction is exerted on the suture and a small wedge incision is made longitudinally on each side of it to resect as small a portion of the wall as possible with a surgical blade. If the biopsy is kept small, there is no need to close the wound transversally to avoid stenosis of the intestinal lumen. As for enterotomy and enterectomy, a 1-layer, full-thickness suture pattern is used for closure.

When removing a linear intestinal foreign body, the number of enterotomies required can be reduced to 1 or 2 by using a urinary catheter for dogs. An enterotomy is made orally (often on the descending duodenum), which allows recovering the oral portion of the foreign body (typically stuck around the base of the tongue in cats and in the pylorus in dogs). The foreign body is then attached to the extremity of the sterile urinary catheter, which is then fed into the intestinal lumen. It is then moved aborally by taxis, until it reaches the ileum. In many cases, it can be moved further aborally and be recovered through the anus by a non-scrubbed assistant. If not, a second enterotomy is made on the ileum to remove the catheter and the entire foreign body from the intestinal lumen.

One-Layer, Full-Thickness Appositional Sutures

Entero- and enterectomy wounds must be sutured in onelayer, appositional sutures to prevent stenosis. Interrupted or continuous sutures can be used. It is critical to include the submucosa in all sutures, which most often means that full-thickness sutures must be used.

Mucosal Eversion Management

When the intestinal wall is incised, the mucosa and submucosa tend to everse, as the fibres of the longitudinal smooth muscle retract. Whereas this is not a factor limiting success, suturing the intestines with everted mucosa leads to second-intention healing of the wound by lack of apposition of layers. Two techniques can be used to suture intestines with everted mucosa: the everted mucosa can be trimmed or modified. Gambee sutures can be used to push the mucosa and submucosa into the lumen as sutures are placed.

Use Continuous Suture Patterns

Whereas using interrupted patterns for closure of entero and enterectomy wounds is not wrong, it is slower and leaves more foreign body in the wounds.

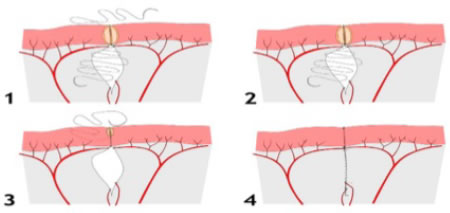

When using a continuous pattern for enterectomy, the suture should be stopped in at least one point 2 separate to avoid creating a purse-string. Either a double-needled suture or 2 sutures (Figure 1) can be used. In all cases, the sutures should be placed in a way that allows intraluminal control of the good apposition of the mesenteric portion intestinal edges, which means that the last portion to be sutured must be the antimesenteric border.

| Figure 1. Intestinal anastomosis in 2 continuous patterns, using 2 single-needled sutures |

|

|

| |

Preserve Jejunal Vessels When Closing The Mesentery

When little tissue is present to close the mesentery without risking damaging the jejunal vessels, a horizontal mattress continuous suture can be used to place suture at a distance, in a vessel-free portion of the mesentery.

Omentalise Without Damaging the Intestine

To omentalise the intestinal wound, the free extremity of the greater omentum can be wrapped around the intestinal loop of interest and sutured on itself through a vessel-free portion of the mesentery, rather than sutured to the small intestine, to limit the trauma to the intestine.

Feed the Gut

Never close an abdomen after intestinal surgery without considering whether a feeding tube should be placed. In most instances, an oesophagostomy tube will be most appropriate, and be placed after the abdomen is closed, but decisions must be made before closure, in case a gastrostomy, gastrojejunostomy or jejunostomy tube would be preferable.

Use Antibiotics Wisely

In the absence of preexisting perforation/rupture or infection, entero- and enterectomies are cleancontaminated surgeries. As such, unless the amount of intestinal damage leads to a risk of bacterial translocation or if intraoperative contamination was significant and could not be addressed satisfactorily, only prophylactic antibiosis should be used (IV antibiotics given at induction and every 90 minutes throughout surgery, discontinued within 12 to 24 hours after surgery). Therapeutic antibiosis (prolongation of antibiotic administration beyond 24 hours postoperatively) should only be used in case of strongly suspected or documented massive contamination or infection.