1. Feline Hypertrophic Cardiomyopathy (CHF)

CHF is the most common primary heart disease in geriatric feline cats. This is characterized by an exaggerated hypertrophy of the walls and septum of the left ventricle without chamber dilation (eccentric hypertrophy). It is important that other alterations that generate similar hypertrophy as hyperthyroidism and hypertension are discarded.

The cause of the CHF has not yet been clearly established. Genetic studies in breeds like the Maine Coon have shown a pattern of autosomal dominant transmission. In humans it has been found that hypertrophic cardiomyopathy is familial due to mutations in some genes that modify the synthesis of proteins of myocytes. In Maine Coon has identified a reduction in the content myosin, a sarcomeric protein.

Macroscopic and Microscopic Changes

Alterations in the proteins of contraction generate an enlarged myocyte what is known as hypertrophy. The sarcomeres are arranged in series by changing the characteristic of striated, thin and aligned to thickened and disorganized cells. They have also found air diffuse or focal fibrosis within the endocardium, myocardium and conduction system. As a result the interior of the ventricular chamber is reduced ventricular filling difficult and increasing the size of the left atrium. Sometimes hypertrophy is segmental which means that you can increase portions of the septum and ventricular wall. Hypertrophy of the papillary muscles causes a change in the geometry of the valve apparatus proper coaptation of preventing the valve flaps.

Pathophysiology

The main problem is generated from the ventricular hypertrophy and diastolic dysfunction. This abnormality is an altered ventricular filling that includes increased pressure and impaired ventricular relaxation. When ventricular compliance is reduced ventricular filling is compromised and therefore ventricular diastolic pressure increases considerably. To better understand these changes it is necessary to study normal diastolic processes.

Diastole is an active period. This means that requires mediated contraction phase and a component myocyte relaxation is the position return of rest of the sarcomeres. Diastole to be effective ventricular pressure should be low, this ensures a wide area and a ventricular suction (mediated contraction) of the blood of the atrium. Furthermore, as the total ventricular filling depends 20% of atrial contraction, this should function normally. If the early phase of diastole becomes slow or is performed incompletely it extends the isovolumetric relaxation, reduce early ventricular filling and atrial contraction increases to compensate for this process.

Clinical Presentation

CHF occurs most often in middle-aged cats, but can be found in young and elderly animals. It has not identified a gender bias, although the disease is seen more in males than in females. Animals can be asymptomatic for a long time.

Bearing in mind the major pathophysiological changes the most common signs presented at the CHF will be analyzed.

Signs of respiratory abnormality: tachypnea, dyspnea, orthopnea; these will result in the presence of pleura effusion or rarely pulmonary edema.

Signs of respiratory abnormality: tachypnea, dyspnea, orthopnea; these will result in the presence of pleura effusion or rarely pulmonary edema.

Sometimes cats come with paralysis of the hind limbs. This may be associated with distal aortic thromboembolism.

Sometimes cats come with paralysis of the hind limbs. This may be associated with distal aortic thromboembolism.

A cardiac auscultation can find a blow on the left chest that radiates to the apical region.

A cardiac auscultation can find a blow on the left chest that radiates to the apical region.

Diagnosis

Radiographic findings depend on the stage of the disease. In cats with mild CHF we cannot find any changes in radiographic views. Over time the cardiac silhouette is beginning to show an enlarged left atrium and dorsal-ventral view the typical silhouette of the heart valentines presents.

Electrocardiographic changes are rare but can be found increase in the amplitude of the R wave and P indicating ventricular hypertrophy and left atrial enlargement. Atrial fibrillation is the most common arrhythmia and occurs in severe atriomegaly. Occasionally you can find a delay in driving the AV node, complete AV block or sinus bradycardia as a result of changes in the conduction system.

The best diagnostic tool is echocardiography and to quantify the thickness of the wall and interventricular septum and determine the presence of diastolic dysfunction. In B-mode images wall hypertrophy, septum and papillary muscles is observed.

This condition is normally distributed symmetrically, but often you can find an asymmetric or focal distribution in different places already mentioned. Because of this use of the M-mode for measurement of the wall and the septum is limited, it is recommended to perform these measurements in different places transverse dimensional images and long axis. It is considered that the walls and interventricular septum this normal diastolic values between 5.0–5.5 mm. Caution should be exercised in making the diagnosis in cats with dehydration and activation of the sympathetic nervous system stress where you can file a pseudohypertrophy. In cases of severe hypertrophy measurements can exceed 8.0 mm, but this does not necessarily correlate with the clinical condition. An important finding that may be associated with the possible signs of congestion is the size of the left atrium; AI/AO ratios above 1.6 indicate enlargement and progressive growth atrium may indicate disease progression. It should assess the echogenicity of the papillary muscles and ventricular walls as hyperechoic areas may indicate fibrosis due to ischemia. When the atrial size is severe there is a possibility of finding thrombi adhering to the atrial wall or free-floating in the atrium or auricle.

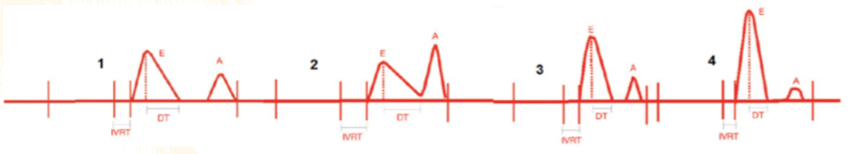

Hemodynamic findings may show changes in diastolic function. This can be evaluated with transmitral flows that determine abnormalities in relaxation or restrictive patterns. Usually the CHF has patterns that include reducing the maximum speed of the wave E, decreased rate of deceleration of the E wave, increasing maximum speed of wave A, reduced E/A ratio and prolongation of isovolumetric relaxation (Figure 1).

| Figure 1 |

Changes in diastolic dysfunction indicators transmitral flows. 1. normal flow; 2. delay in relaxation; 3. pseudonormal; 4. restrictive pattern. DT: deceleration time, IVRT: isovolumetric relaxation time. |

|

| |

Treatment

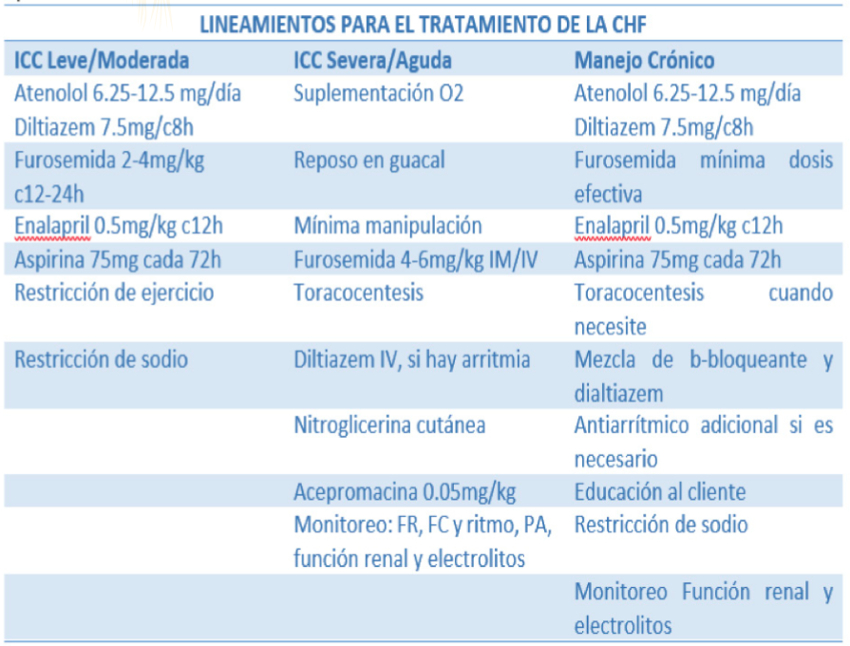

The goals of treatment are to facilitate the ventricular filling, minimizing danger or congestion, control arrhythmias, ischemia minimize and reduce thromboembolism (Table 1).

| Table 1 |

|

|

| |

Source: Adapted (Ware, 2007).

The use of b-blockers or diltiazem is performed to improve ventricular filling and avoid myocardial ischemia. Should be avoided in cats with myocardial failure or marked and continuing bradycardia. The use of inhibitors of angiotensin converting enzyme is in order to block the neurohormonal cascade and thus stop ventricular remodeling. Although not entirely clear that their effectiveness in cats. A broad debate exists on the use in asymptomatic animals with CHF as preventive therapies has not been able to clearly demonstrate whether this slows the onset of signs and improves the quality of life of these. Antithrombotic therapy is initiated when the left atrium has an exaggerated increase or when "smoke" is observed in it compatible with platelet aggregation and high risk of thromboembolism.

Use of furosemide is required when the cat shows signs of congestion, mainly pulmonary edema or pleural effusion (EPL). It is important to clarify that the use of diuretics in patients with effusion is done to prevent re-offending to fix the problem therefore must in all cats with EPL thoracocentesis.

The prognosis of CHF depends on the time in which the patient is diagnosed. In an initial asymptomatic period and the prognosis is good, as long as subsequent revisions in heart size remains stable. When the animal arrives with severe hypertrophy, and signs of congestion megaatrio the prognosis is poor because the animal can die within a relatively short period. With aortic thromboembolism animal has low chances of recovering the mobility of its members and a high risk of repeat embolic events in other regions of the body.

References

1. Ware W. Myocardial diseases of the cat. In: Cardiovascular Disease in Small Animals Medicine. London, UK: The Veterinary Press; 2007.

2. Ferasin L. 1. Feline myocardial disease. Journal of Feline Medicine and Surgery. 2009;11:3–13.

3. Ferasin L. 2. Feline myocardial disease: Journal of Feline Medicine and Surgery. 2009;11:183–194.

Cardiología y Gatos Viejos

Leonardo Gómez Duarte

Unidad de Cardiología Veterinaria, Bogota, Colombia

Cardiomiopatia Hipertrófica Felina (CHF)

La CHF es la cardiopatía primaria felina más común en gatos geriatricos. Esta se caracteriza por un hipertrofia exagerada de las paredes y septum del ventrículo izquierdo sin dilatación de la cámara (hipertrofia excéntrica). Es importante que se descarten otras alteraciones que generan una hipertrofia similar como el hipertiroidismo y la hipertensión arterial sistémica.

La causa de la CHF aun no se ha establecido claramente. Estudios genéticos en razas como el Maine Coon han demostrado un patrón de transmisión autosómica dominante. En humanos se ha encontrado que la cardiomiopatía hipertrófica es de tipo familiar debido a mutaciones en algunos genes que modifican la síntesis de las proteínas de los miocitos. En los Maine Coon se ha identificado una reducción en el contenido de miomesina, una proteína sarcomérica.

Cambios Macroscópicos y Microscópicos

Las alteraciones de las proteínas de la contracción generan un aumento del tamaño del miocito lo que se conoce como hipertrofia. Las sarcomeras se acomodan en serie cambiando la característica de células estriadas, delgadas y alineadas a engrosadas y desorganizadas.

También se han encontrado aéreas difusas o focales de fibrosis dentro del endocardio, sistema de conducción y miocardio. Como resultado el interior de la cámara ventricular se reduce dificultando el llenado ventricular y aumentando el tamaño del atrio izquierdo. En algunas ocasiones la hipertrofia es segmentaria lo que significa que se puede aumentar porciones del septum y de la pared ventricular. La hipertrofia de los músculos papilares causa un cambio en la geometría del aparato valvular impidiendo la adecuada coaptación de las aletas valvulares.

Fisiopatología

El principal problema que se genera a partir de la hipertrofia ventricular es la disfunción diastólica. Esta anormalidad consiste en una alteración del llenado ventricular que incluye aumento de la presión ventricular y alteraciones en la relajación. Cuando la compliance ventricular se reduce se dificulta el llenado ventricular y por lo tanto la presión ventricular en diástole aumenta considerablemente. Para comprender mejor estos cambios se requiere estudiar los procesos diastólicos normales.

La diástole es un período activo. Esto significa que requiere de una fase de contracción mediada por los miocitos y un componente de relajación que es el retorno a la posición de reposos de las sarcomeras. Para que la diástole sea efectiva la presión ventricular debe ser baja, esto se garantiza con un área ventricular amplia y con una succión (mediada por la contracción) de la sangre del atrio. Además como el llenado total del ventriculo depende en un 20% de la contracción auricular, esta debe funcionar normalmente.

Si la fase temprana de la diástole se vuelve lenta o se realiza de manera incompleta se prolonga el tiempo de relajación isovolumétrica, reduce el llenado ventricular temprano e incrementa la contracción atrial para compensar este proceso.

Presentación Clínica

La CHF se presenta con mayor frecuencia en gatos de edad media, pero se puede encontrar en animales jóvenes y geriátricos. No se ha identificado una predisposición por género, aunque se ve la enfermedad más en machos que en hembras. Los animales pueden ser asintomáticos durante mucho tiempo.

Teniendo presente las principales alteraciones fisiopatológicas se analizará los signos más comunes presentados en la CHF.

Signos de anormalidad respiratoria: taquipnea, disnea, ortopnea; estos se dan como resultado de la presencia de efusión pleura o en raras ocasiones edema pulmonar.

Signos de anormalidad respiratoria: taquipnea, disnea, ortopnea; estos se dan como resultado de la presencia de efusión pleura o en raras ocasiones edema pulmonar.

En algunas ocasiones los gatos llegan con parálisis de los miembros posteriores. Esto se puede asociar al tromboembolismo aórtico distal.

En algunas ocasiones los gatos llegan con parálisis de los miembros posteriores. Esto se puede asociar al tromboembolismo aórtico distal.

A la auscultación cardiaca se puede encontrar un soplo en el hemitórax izquierdo que irradia hacia la región apical.

A la auscultación cardiaca se puede encontrar un soplo en el hemitórax izquierdo que irradia hacia la región apical.

Diagnóstico

Los hallazgos radiográficos dependen del estadio de la enfermedad. En gatos con CHF leve es posible no encontrar cambios en ninguna de las vistas radiográficas. Al pasar el tiempo la silueta cardiaca va empezando a mostrar un agrandamiento del atrio izquierdo y en la vista dorso ventral se presenta la típica silueta del corazón de san valentin.

Los cambio electrocardiográficos son poco frecuentes pero se puede encontrar aumento de la amplitud de la onda R y la P indicando hipertrofia ventricular y agrandamiento auricular izquierdo. La fibrilación auricular es la arritmia más frecuente y se da en atriomegalias severas. Ocasionalmente se puede encontrar un retardo en la conducción al nodo AV, bloqueo AV completo o bradicardia sinusal como resultado de los cambios en el sistema de conducción.

La mejor herramienta diagnóstica es la ecocardiografía ya que permite cuantificar el grosor de la pared y el septum interventricular y determinar la presencia de disfunción diastólica. En las imágenes en modo B se observa hipertrofia de la pared, septum y músculos papilares.

Esta condición normalmente se distribuye simétricamente, pero con frecuencia se puede encontrar una distribución asimétrica o focal en los diferentes lugares ya mencionados. Debido a esto el uso del modo-M para realizar la medición de la pared y el septum es limitado, se recomienda realizar estas medidas en diferentes lugares de imágenes bidimensionales transversales y de eje largo. Se considera que las paredes y el septum interventricular esta normal con valores en diástole entre 5.0–5.5 mm. Hay que tener precaución en la realización del diagnóstico en gatos con deshidratación y activación del sistema nervioso simpático por estrés donde se puede presentar una pseudohipertrofia. En casos de hipertrofia severa las mediciones pueden superar los 8.0 mm, pero esto no se correlaciona necesariamente con la condición clínica. Un hallazgo importante que puede asociarse con la posible aparición de signos de congestión es el tamaño del atrio izquierdo; relaciones AI/AO superiores a 1.6 indican agrandamiento del atrio y su crecimiento progresivo puede indicar avance de la enfermedad. Se debe evaluar la ecogenicidad de los músculos papilares y paredes ventriculares ya que zonas hiperecogénicas pueden indicar fibrosis debido a isquemia. Cuando el tamaño atrial es severo existe la posibilidad de encontrar trombos adheridos a la pared atrial o flotando libres en el atrio o aurícula.

Los hallazgos hemodinámicos pueden mostrar cambios en la función diastólica. Esta se puede evaluar con los flujos transmitrales que determinar anormalidades en la relajación o patrones restrictivos. Habitualmente la CHF presenta patrones que incluyen reducción de la velocidad máxima de la onda E, disminución de la tasa de desaceleración de la onda E, incremento de la velocidad máxima de la onda A, reducción de la relación E/A y prolongación del tiempo de relajación isovolumétrica (Figura 1).

Figura 1

Caption: Cambios en los flujos transmitrales indicadores de disfunción diastólica. 1. flujo normal; 2. retardo en la relajación; 3. pseudonormal; 4. Patrón restrictivo. DT: tiempo de desaceleración, IVRT: tiempo de relajación isovolumétrica.

Manejo

Los objetivos del tratamiento son facilitar el llenado ventricular, disminuir los riegos o la congestión, controlar las arritmias, minimizar la isquemia y disminuir el tromboembolismo (Tabla 1).

Tabla 1

El uso de b-bloqueadores o dialtiazem se realiza para mejorar el llenado ventricular y evitar la isquemia miocárdica. Se debe evitar en gatos con insuficiencia miocárdica o bradicardia marcada y continua. El uso de los inhibidores de la enzima convertidora de angiontensina es con el fin de bloquear la cascada neurohormonal y así detener el remodelado ventricular. Aun no esa totalmente claro su efectividad en los gatos. Existe un amplio debate sobre el uso en animales asintómaticos con CHF de terapias preventivas ya que no se ha podido demostrar claramente si esta enlentece la aparición de los signos y mejora la calidad de vida de estos. La terapia antitrombótica se inicia cuando el atrio izquierdo tiene un aumento exagerado o cuando se observa "humo" en él compatible con agregación plaquetaria y alto riesgo de tromboembolismo.

El uso de furosemida es necesario cuando el gato presenta signos de congestión, principalmente edema pulmonar, o efusión pleural (EPL). Es importante aclarar que el uso de diuréticos en pacientes con efusión se hace para evitar que reincida el problema no para solucionarlo, por lo tanto se debe en todos los gatos con EPL realizar toracocentesis.

El pronóstico de la CHF depende del momento en el cual se diagnostique el paciente. En un periodo inicial y asintomático el pronóstico es bueno, siempre y cuando en las revisiones posteriores el tamaño del corazón se mantenga estable. Cuando el animal llega con hipertrofia severa, megaatrio y signos de congestión el pronóstico es malo ya que el animal puede morir en un período relativamente corto. Con tromboembolismo aórtico el animal tiene bajas posibilidades de recuperar la movilidad de sus miembros y un alto riesgo de repetir los episodios embólicos en otras regiones del cuerpo.

Bibliografia

1. Ware W. Myocardical diseases of the cat. In: Cardiovascular Disease in Small Animals Medicine. London, UK: The Veterinary Press; 2007.

2. Ferasin L. 1. Feline myocardical disease. Journal of Feline Medicine and Surgery. 2009;11:3–13.

3. Ferasin L. 2. Feline myocardical disease: Journal of Feline Medicine and Surgery. 2009;11:183–194.