Abstract

Wild passerines worldwide frequently experience outbreaks of salmonellosis associated with strains of (Salmonella typhimurium). From January through April of 2008, the National Zoo experienced an outbreak of salmonellosis in 12 wild house sparrows (Passer domesticus) in two geographic locations on zoo grounds. Affected birds had inflammation and necrosis in the liver, spleen, crop, skin, eyes, adrenal gland, lung, intestine and ovary. Two birds also had bacterial granulomas in the brain. Abatement was attempted during the third month of the outbreak via depopulation of the house sparrow complement in one geographic location. All depopulated birds were examined grossly and carrier status or early infection was found in one of these birds via culture. Salmonella-positive birds continued to be submitted for necropsy following abatement indicating that depopulation may slow, but does not halt, outbreaks of Salmonella.

Introduction

Salmonellosis in wild passerines is a relatively common occurrence in late winter and early spring and has been documented worldwide, including in Norway,6,7 Japan,8 Canada,1 and in multiple states in the United States3-5. Outbreaks usually occur from January through April and are associated with several different strains of S. typhimurium, most commonly DT104, though Copenhagen and DT40 strains have also been commonly implicated.

During the first 4 months of 2008, the National Zoo experienced an outbreak of S. typhimurium in house sparrows in the elephant house and around the bird house. This paper describes the pathologic aspects of the outbreak and the abatement efforts undertaken to halt or slow the outbreak in one portion of the zoo.

Materials and Objectives

Throughout the year, wildlife found dead or euthanatized due to illness on the grounds of the National Zoo is submitted to the Department of Pathology for gross examination. Certain cases are processed further for histopathology, cytology, culture or other ancillary diagnostic procedures. During this time, 112 wild birds were examined grossly and 33 were evaluated histologically. Cultures were obtained from 34 birds with sources including heart blood, and swabs of the coelomic cavity, crop wall, intestinal lumen, and brain granuloma. Samples were inoculated onto Difco™ SS Agar, BBL™ MacConkey Agar, and BBL™ GN Broth which were prepared according to package directions (Becton, Dickinson and Company, Sparks, MD 21152). After 24 hours of incubation, suspected colonies were inoculated onto one of each TSI and LIA agar. Further identification was made using the api® 20E identification system. If the organism was identified as Salmonella sp., a subculture on nutrient agar was sent to the U.S. Department of Agriculture, Animal and Plant Health Inspection Service, National Veterinary Services Laboratories in Ames, IA 50010 for further classification.

Abatement practices undertaken on 12 March included capture of wild birds via mist net within the indoor elephant enclosure and euthanasia of house sparrows. Birds of other species were released. Cursory gross necropsies were performed on the 61 euthanatized house and nine birds were cultured for Salmonella.

Results

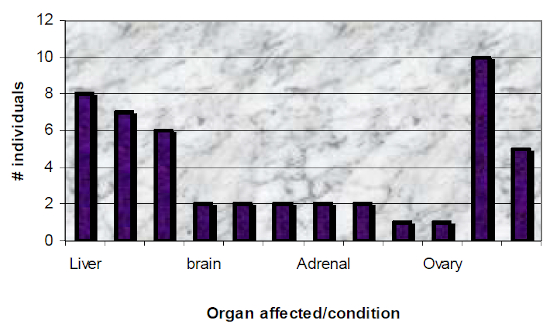

From January through April 2008, 51 wild birds that were found dead on zoo grounds were submitted for necropsy examination. These included 23 house sparrows (Passer domesticus), 20 mallards (Anas playtrhynchos), 6 European starlings (Sternus vulgaris), 2 American robins (Turdus migratorius), and 1 each Carolina wren (Thryothorus ludovicianus), piliated woodpecker (Dryocopus piliatus), cardinal (Cardinalis cardinalis), common grackle (Quiscalus quiscula), white-throated sparrow (Zonotrichia albicollis), downy woodpecker (Picoides pubescens), mourning dove (Zenaida microaura), horned grebe (Podiceps auritus), and domestic chicken (Gallus gallus). An additional 61 house sparrows were euthanatized in the abatement effort. Of these 112 birds, 12 (10.7%) were found to be positive for S. typhimurium via culture (nine) or had gross or histologic lesions consistent with salmonellosis (three). All affected birds were house sparrows found dead or ill in the elephant house or around the bird house. Lesions were generally necrotizing, but in some areas such as the brain, the inflammatory process produced a granuloma. All birds examined histologically had two or more organs affected by salmonellosis with up to 5 organs showing necrotizing or granulomatous lesions. Lesion location and other conditions are outlined in Figure 1. Grossly, fat and/or muscle depletion was seen in 10 (83%) affected birds. Splenomegaly was documented in five (42%). Histologic lesions specifically attributed to Salmonella infection were most commonly seen in the liver (8), crop (7), and spleen (6). Lesions in the brain, skin, eyes, adrenal gland, and lung were seen in two animals each. The intestinal serosa and ovary was affected in one bird each. All house sparrows captured in the abatement effort were grossly unremarkable. One grew S. typhimurium from a coelomic swab.

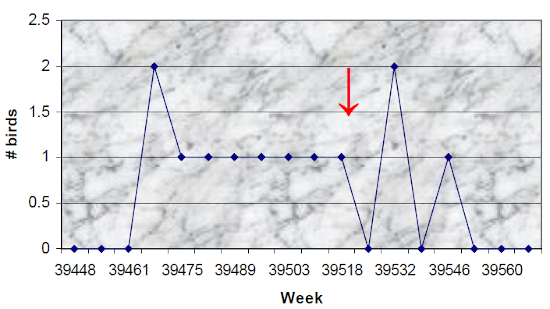

The temporal distribution of the outbreak is outlined in Figure 2. In the first week of the outbreak, two birds were found to be Salmonella-positive, with one positive bird found in each of the subsequent 6 weeks until the abatement effort. One week after abatement, no birds were found dead within the zoo; however, in the following 3 weeks, three birds were found with lesions of salmonellosis. The last Salmonella-positive sparrow of 2008 was submitted for necropsy on April 14, 2008.

Figure 1

Pathologic changes in house sparrows infected with Salmonella typhimurium.

Figure 2

Salmonella-positive house sparrow submission by week. Abatement occurred on 3/12/2008.

Discussion and Conclusions

Lesions found in the birds of this study, most notably necrotizing hepatitis, splenitis, and fibrinonecrotic ingluvitis, are similar to those described in other surveys involving multiple species of songbirds.1,4,8 This is the first documentation, to our knowledge, of cerebral granulomas and ocular lesions associated with S. typhimurium. One report of meningitis in a rock pigeon (Columba livia) was associated with S. typhimurium,4 but the lesion was not further characterized. In one sparrow of this report, a cerebral granuloma was associated with retinitis, suggesting that bacterial infection spread along the route of the optic nerves. As histopathology of this condition in wild birds is not reported in detail, it is possible that microscopic alterations in birds of previous reports went unnoticed. Additionally, the brain may not be consistently examined in some studies.

Salmonella is long lived in the environment and will persist for up to 16 months in highly organic material.2 Outbreaks have been associated with bird feeders where songbirds may aggregate and contract the bacterium from carrier animals or fomites.1,2,7 Eight of the 12 (67%) affected house sparrows in this case came from the elephant house, a large enclosure housing three elephants, two hippopotamuses and three capybaras around a large, central, public area. No concentrated feeding of wild birds takes place, but sparrows are regularly seen in the hay feed area. Three affected sparrows came from outside the bird house area and one had been handled by a giant panda. Interestingly, fecal cultures of the collection species in proximity to where the affected sparrows were found, including outdoor species of bustard and crane, were consistently negative for Salmonella. This may reflect the host adaptation that some variants of Salmonella display.2

Broad scale capture by mist netting and euthanasia of 61 house sparrows in the elephant house was undertaken primarily to reduce the number of birds that could possibly transmit or carry the bacterium and secondly to survey the population for carriers of the disease. The activity only temporarily stalled the 7-week trend of carcass submissions that were positive for Salmonella, and the outbreak continued into April. Most studies describe outbreaks peaking from January into April,1,7 as was the case here, and most hypotheses point to the heavier use of bird feeders during this time as a cause. Removal of this variable in the birds studied at the National Zoo, and a smaller, though similar Salmonella outbreak at NZP at the same time the following year, may indicate that other factors play a significant role in spread of the disease. Further evaluation into the epidemiology and pathology of passerine salmonellosis is warranted.

Acknowledgments

Many thanks to necropsy prosectors: Linda Meola, Mauricio Guayasamin, Gwynne Kinley, Elizabeth Arguelles, Todd Bell, Tim Walsh, and Katrina Villiard, and to Ann Bratthauer for sample processing.

Literature Cited

1. Daoust, P-Y., D. G. Busby, L. Ferns, J. Goltz, S. McBurney, C. Poppe, and H. Whitney. 2000. Salmonellosis in songbirds in the Canadian Atlantic provinces during winter-summer 1997–98. Can. Vet. J. 41: 54–59.

2. Daoust, P-Y., J. F. Prescott. 2007. Salmonellosis. In: Thomas, N. J., D. B. Hunter, and C. T. Atkinson. Infectious Diseases of Wild Birds. Blackwell Publishing, Ames, Iowa. Pp. 270–288.

3. Hall, A. J., and E. K. Saito. 2008. Avian wildlife mortality events due to salmonellosis in the Unites States, 1985–2004. J. Wildl. Dis. 44: 585–593.

4. Hudson, C. R., C. Quist, M. D. Lee, K. Keyes, S. V. Dodson, C. Morales, S. Sanchez, D. G. White, and J. J. Maurer. 2000. Genetic relatedness of Salmonella isolates from nondomestic birds in southeastern Unites States. J. Clin. Microbiology. 38: 1860–1865.

5. Morishita, T. Y., P. P. Aye, E. C. Ley, and B. S. Harr. 1999. Survey of pathogens and blood parasites in free-living passerines. Av. Dis. 43: 549–552.

6. Refsum, T., K. Handeland, D. L. Baggesen, G. Holstad, and G. Kapperud. 2002. Salmonellae in avian wildlife in Norway from 1969 to 2000. App. Env. Microbiol. 68: 5595–5599.

7. Refsum, T., T. Vikoren, K. Handeland, G. Kapperus, and G. Holstad. 2003. Epidemiologic and pathologic aspects of Salmonella typhimurium infection in passerine birds in Norway. J. Wildl. Dis. 39: 64–72.

8. Une, Y., A. Sanbe, S. Suzuki, T. Niwa, K. Kawakami, R. Kurosawa, H. Izumiya, H. Watanabe, and Y. Kato. 2008. Salmonella enterica serotype typhimurium infection causing mortality in Eurasian tree sparrows (Passer montanus) in Hokkaido. Jap. J. Inf. Dis. 61: 166–167.