Introduction

The veterinary profession recognises the importance of evidence-based medicine and The Royal College of Veterinary Surgeons states 'How to evaluate evidence' as an essential day one competence required of all veterinary surgeons. A vast number of scientific papers are published every year on new treatments or therapies. Although many of these are in reputable journals and have been through a process of peer review by experts, the quality is still variable. In addition there are many sources of non-peer-reviewed literature, including text books and the Internet. It is therefore up to the individual veterinary surgeon to determine the extent to which the results in a paper can be applied to the particular question they are interested in, and the strength of evidence of the work. In some instances the reader may be presented with papers containing insufficient information to appraise reliability and these should be interpreted with caution.

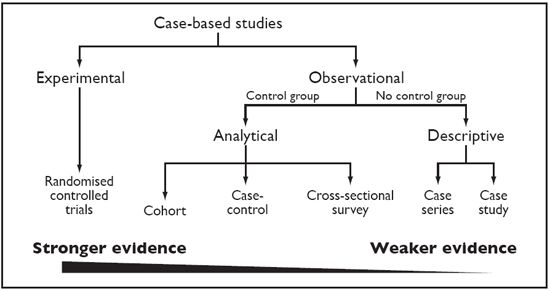

Understanding the type of study that has been performed is a prerequisite to evaluation of the strength of evidence provided by the study. In addition knowledge of the design will enable the reader critically appraising the paper to determine whether the study in question has been appropriately designed and conducted, and, if not, whether this should decrease the strength of belief in the results (or if they should be believed at all!). Clinical research studies can be divided into observational or experimental. Observational studies can be further divided into descriptive and analytical. Figure 1 shows a schematic representation of study types and the strength of evidence they provide.

| Figure 1. Types of clinical research studies and the strength of evidence they provide. |

|

|

| |

Descriptive studies include case reports and case series. These are commonly seen in the veterinary literature (and commonly) used when describing the use of new therapies. However, case report and case series are not designed to test an association between a therapy and a treatment. If an author draws conclusions about the merits of a particular therapy from a case report or series, this should be regarded as the author's opinion/conjecture only, as these provide no data to support this. Case reports and series can be useful in generating hypotheses about new therapies but these should then be further tested in a rigorous analytical study.

We can divide analytical studies into observational or experimental studies. In experimental studies the investigator controls the allocation of study subjects to treatment or therapy groups (new treatment versus non/old treatment). In the controlled trials the investigator controls allocation of subjects to treatment groups but this is done under 'real world' conditions (as opposed to laboratory-based). The investigator then tries to make comparisons between groups of study animals to make inferences about the effect of a therapy on the outcome of interest.

As can be seen from Figure 1 of all the study types the 'randomised controlled trial' (RCT) provides the strongest evidence and the RCT is regarded as the unchallenged source of the highest standard of evidence to guide clinical decision making. Unfortunately, in contrast to medical literature, there are few published randomised controlled trials in the veterinary literature. A search by Polton and Scase of the veterinary literature revealed only 13 randomised controlled clinical trials in cats and dogs (with a total of 1157 cases). However, there are many more non-randomised, non-blinded trials in the veterinary literature, and many based on retrospective reviews of animals treated with different therapies. As these studies do not adhere to the strict criteria required for an RCT, the conclusions from such studies may be unreliable.

Key Issues to Consider in the Controlled Trial

The randomised, blinded, controlled trial provides the strongest evidence because this design provides the best means of avoiding selection and confounding biases in clinical research. The process of random allocation to treatment groups reduces selection bias and confounding (both known and unknown). The process of blinding reduces information or measurement bias. These and other important factors must be considered when reviewing a controlled trial. The following critical appraisal checklist can be used to identify whether the research documented in the paper conforms to certain criteria important in a controlled trial. It is up to the reader to determine the extent to which she/he feels the results are reliable and whether the new or alternate therapy under test is of potential benefit to patients under their care.

Critical Appraisal Checklist for an Article About Treatment or Therapy

Description of the Evidence

What was the main aim (hypothesis or objective) of the study? This should be clearly stated and include:

What was the main aim (hypothesis or objective) of the study? This should be clearly stated and include:

What was the treatment or therapy under test?

What was the treatment or therapy under test?

What was the primary outcome to be measured? A controlled trial should have a limited number of objectives. Examples of different outcomes which might be relevant when investigating a new therapy include: preventing mortality; increasing survival time; reducing unwanted side effects and other clinical outcomes such as degree of lameness etc. (it may be difficult to develop reliable clinical scores for measuring the severity of disease). Studies with multiple outcomes may complicate the protocol and may lead to multiple statistical tests being performed, which increases the risk of type I error.

What was the primary outcome to be measured? A controlled trial should have a limited number of objectives. Examples of different outcomes which might be relevant when investigating a new therapy include: preventing mortality; increasing survival time; reducing unwanted side effects and other clinical outcomes such as degree of lameness etc. (it may be difficult to develop reliable clinical scores for measuring the severity of disease). Studies with multiple outcomes may complicate the protocol and may lead to multiple statistical tests being performed, which increases the risk of type I error.

What was the trial design?

What was the trial design?

Did the study compare a new treatment to an existing standard therapy or was a placebo used?

Did the study compare a new treatment to an existing standard therapy or was a placebo used?

What kind of trial: simple 'two arm' randomised controlled trial'; cross-over design (each subject gets both interventions--suitable for chronic conditions); factorial design (if testing more than one intervention)?

What kind of trial: simple 'two arm' randomised controlled trial'; cross-over design (each subject gets both interventions--suitable for chronic conditions); factorial design (if testing more than one intervention)?

What was the study population?

What was the study population?

Which animals was the trial carried out on (these should be representative of the population to which you want the results of the trial to apply)?

Which animals was the trial carried out on (these should be representative of the population to which you want the results of the trial to apply)?

What were the eligibility criteria: what was the case definition for the disease/condition under trial? Were there any exclusions?

What were the eligibility criteria: what was the case definition for the disease/condition under trial? Were there any exclusions?

Are the Results of the Study Valid? (Internal Validity)

Was the assignment of animals to treatment groups randomised (vs. haphazard assignment or 'based on clinician preference' or 'owner circumstances')?

Was the assignment of animals to treatment groups randomised (vs. haphazard assignment or 'based on clinician preference' or 'owner circumstances')?

Were all animals that entered the trial properly accounted for at its conclusion? (Was follow-up complete or were some animal 'lost' from the trial?)

Were all animals that entered the trial properly accounted for at its conclusion? (Was follow-up complete or were some animal 'lost' from the trial?)

Were subjects analysed in the group to which they were allocated even if they didn't complete the treatment? (Was analysis by intention-to-treat or by per-protocol?)

Were subjects analysed in the group to which they were allocated even if they didn't complete the treatment? (Was analysis by intention-to-treat or by per-protocol?)

Was the study blinded? This may be single, double or triple--i.e., were owners, clinicians (or those assessing the outcomes) and other study personnel (those analysing the data) blinded to the treatment allocation?

Was the study blinded? This may be single, double or triple--i.e., were owners, clinicians (or those assessing the outcomes) and other study personnel (those analysing the data) blinded to the treatment allocation?

Were the groups similar in clinically important factors at the start of the study? (Clinically important may include age, breed etc. as well as presenting clinical signs. Proper randomisation should ensure this.)

Were the groups similar in clinically important factors at the start of the study? (Clinically important may include age, breed etc. as well as presenting clinical signs. Proper randomisation should ensure this.)

Aside from the experimental therapies, were the groups treated equally (i.e., were they followed and assessed in a similar manner)?

Aside from the experimental therapies, were the groups treated equally (i.e., were they followed and assessed in a similar manner)?

Did the study have sufficient statistical power and were appropriate statistical methods used?

Did the study have sufficient statistical power and were appropriate statistical methods used?

What Were the Results?

How large was the estimate of the treatment effect? Is the relationship important/strong? Was there a dose response relationship?

How large was the estimate of the treatment effect? Is the relationship important/strong? Was there a dose response relationship?

How precise (95% CI or SE) was the estimate of the treatment effect? Is the difference statistically significant?

How precise (95% CI or SE) was the estimate of the treatment effect? Is the difference statistically significant?

Will the Results Help Me in Caring for My Patients? (External Validity)

Can the results be applied to my patients? Would my patients have been eligible for the study? Are there any reasons why the results should not be applied to my patients?

Can the results be applied to my patients? Would my patients have been eligible for the study? Are there any reasons why the results should not be applied to my patients?

Were all clinically important outcomes considered?

Were all clinically important outcomes considered?

Are the likely treatment benefits worth the potential harm (side effects) and costs?

Are the likely treatment benefits worth the potential harm (side effects) and costs?

Comparison of the Results with Other Evidence

Are the results consistent with other evidence?

Are the results consistent with other evidence?

Are There Likely to Be Conflicts of Interest?

Who conducted/funded the study?

Who conducted/funded the study?

References

1. Dohoo I, Martin W, Stryhn H. Controlled trials. In: Veterinary Epidemiologic Research. AVC Inc. PEI, Canada, 2003: 185-205.

2. Guyatt GH, Sackett D, Cook DJ. How to use an article about therapy or prevention: http://www.cche.net/usersguides/therapy.asp. Based on the Users' Guides to Evidence-based Medicine and reproduced with permission from JAMA. (1993; 270: 2598-2601) and (1994; 271: 59-63). Copyright 1995, American Medical Association.

3. Polton G, Scase T. Collaborative clinical research in small animal practice. Journal of Small Animal Practice 2007; 48: 357-358.

4. Schulz KF, Grimes DA. Epidemiology Series. The Lancet 2002; 359, Issues 9300-9310.