Fundus assessment should be part of any ocular examination but is particularly important in patients with compromised vision, intraocular inflammation, glaucoma and altered globe-orbit relationship. The choice of instrumentation for the task now includes a user-friendly ophthalmoscope, the PanOptic by Welch-Allyn. But visualisation of the fundus structures is only one part of the process. Successful interpretation requires a thorough understanding of fundus anatomy, an appreciation of the contributions of each component to the overall clinical picture and an understanding of basic responses within the component layers that can alter the fundus's classical appearance.

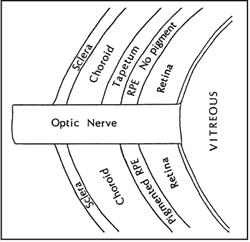

The fundus is defined as the posterior portion of the globe, viewed through the pupil with an ophthalmoscope. Its appearance is a composite picture formed by the optic papilla, sensory retina, retinal pigment epithelium, choroid, tapetum and sclera (Figure 1)--a picture influenced by the animal's breed, age and coat colour.

Click on the figure to see a larger view.

| Figure 1. The components of the fundus. RPE (retinal pigmented epithelium). |

|

|

| |

Normal Fundus Features

Sclera

There are fewer variations in the appearance of the sclera than in any of the other tissues of the fundus. The normal sclera is white to pale yellow in colour. Its visibility depends upon the degree of pigmentation in the overlying choroid and retinal pigmented epithelium, as well as the degree of tapetal development.

Choroid

The choroid, or posterior uvea, lies adjacent to the sclera and originates from cilioretinal vessels that pierce the globe adjacent to the optic nerve. The normal choroidal vessels should be uniform in size and radiate from the optic papilla in spoke-like fashion. The spaces between the choroidal vessels should be small and of uniform size. The choroidal vasculature itself is rarely a complete barrier to visualisation of the underlying sclera. The most common normal variation of the choroid involves its degree of pigmentation. The choroid may be so pigmented that its vasculature is barely discernible or it may be totally devoid of pigment, allowing a clear view not only of the choroidal vessels but of the sclera as well. Choroidal pigmentation, like that of the retinal pigmented epithelium, is determined by the same factors that govern coat pigmentation. In those heavily pigmented breeds, melanin lies interspersed between the large vessels of the choroid.

Tapetum

The tapetum is a layer of reflective cells that lies in the dorsal half of the fundus, between the retinal pigmented epithelium (RPE) and the choroid. The reflectivity of the tapetum is dependent upon its cellular density, which is greater in the cat than in the dog. The most important normal variation of the tapetum is in its size and degree of development. In the normal cat, pigmentation of the RPE gradually diminishes as it approaches the tapetum. The tapetum in turn thickens, resulting in a gradual change in colour at its periphery.

Retina

The typical mammalian retina consists of ten layers. For clinical purposes, the retina behaves as two layers: the retinal pigmented epithelium (RPE) and the neurosensory retina. The RPE is a monolayer of epithelial cells adjacent to the choroid. The RPE is either lightly pigmented (in the ventral fundus) or not pigmented at all (overlying the tapetum). The normal variations of RPE pigmentation influence the visibility of the underlying choroid.

Adjacent and attached to the RPE is the semitransparent sensory retina, whose contribution to the normal fundus is the most subtle of all the fundus layers. The primary influence of the sensory retina is to diminish the reflectivity of the tapetal layer. Unlike the choroid and RPE, there are no normal variations of the sensory retina per se, although variations of the vessels that occupy the superficial layers of the sensory retina do occur.

Optic Disc

The final structure that contributes to the appearance of the fundus is the intraocular portion of the optic nerve, termed the optic disc, optic papilla, or optic nerve head. In cats, the papilla varies little, being unmyelinated and perfectly circular. In contrast, the canine papilla has marked variations in myelination and may assume many shapes.

Normal Feline Fundus

Tapetum

The tapetum is located in the dorsal fundus and is more extensive in the cat than the dog, with a nearly circular shape.

The tapetum is located in the dorsal fundus and is more extensive in the cat than the dog, with a nearly circular shape.

Tapetal colour varies but is most often yellow or green (or combinations thereof).

Tapetal colour varies but is most often yellow or green (or combinations thereof).

The feline tapetum is more reflective than that of the dog and may be misinterpreted as overly reflective by those unaccustomed to examination of the feline eye.

The feline tapetum is more reflective than that of the dog and may be misinterpreted as overly reflective by those unaccustomed to examination of the feline eye.

In Siamese and other colour-dilute breeds, tapetal thinning may expose underlying choroidal vessels. The localised areas of redness may be misinterpreted as haemorrhage.

In Siamese and other colour-dilute breeds, tapetal thinning may expose underlying choroidal vessels. The localised areas of redness may be misinterpreted as haemorrhage.

The area centralis, a relatively cone-dense, avascular area slightly temporal and superior to the optic disc, may vary slightly in reflectivity compared to adjacent tissue.

The area centralis, a relatively cone-dense, avascular area slightly temporal and superior to the optic disc, may vary slightly in reflectivity compared to adjacent tissue.

Cats may have a slightly different tapetal colour immediately surrounding the optic disc.

Cats may have a slightly different tapetal colour immediately surrounding the optic disc.

Non-Tapetum

The inferior half of the fundus is variably coloured by pigment in the retinal pigmented epithelium (RPE) and the choroid that obscures the underlying choroidal vessels.

The inferior half of the fundus is variably coloured by pigment in the retinal pigmented epithelium (RPE) and the choroid that obscures the underlying choroidal vessels.

The junction between tapetum and non-tapetum is gradual rather than distinctive.

The junction between tapetum and non-tapetum is gradual rather than distinctive.

The non-tapetum of most feline patients is light brown to almost black in colour. Colour-dilute breeds like the Siamese will have minimal non-tapetal pigment. The non-tapetal region in these patients is typically red in colour, often with a distinctive striped pattern created by the exposed choroidal vessels.

The non-tapetum of most feline patients is light brown to almost black in colour. Colour-dilute breeds like the Siamese will have minimal non-tapetal pigment. The non-tapetal region in these patients is typically red in colour, often with a distinctive striped pattern created by the exposed choroidal vessels.

Retinal Vessels

Typically three major paired arteries and veins arise from the periphery of the optic disc. These vessels do not cross the optic disc nor anastomose centrally as seen in the dog.

Optic Disc

The optic disc is approximately 1 mm in diameter, smaller than that of the dog, and almost invariably and distinctively round in shape.

The optic disc is approximately 1 mm in diameter, smaller than that of the dog, and almost invariably and distinctively round in shape.

Myelination of the optic nerve ends as it perforates the lamina cribrosa, giving the disc a slightly depressed appearance and darker peach colour than that of the dog.

Myelination of the optic nerve ends as it perforates the lamina cribrosa, giving the disc a slightly depressed appearance and darker peach colour than that of the dog.

The disc is invariably located in the inferior tapetal fundus.

The disc is invariably located in the inferior tapetal fundus.

The physiological cup, a small cleft near the centre of the optic disc representing the termination of the hyaloid canal, is less easily seen in the cat than the dog.

The physiological cup, a small cleft near the centre of the optic disc representing the termination of the hyaloid canal, is less easily seen in the cat than the dog.

Interpreting Fundus Lesions

The following questions summarise the important features to be determined during examination of the fundus:

Are all parts of the fundus in focus simultaneously?

Are all parts of the fundus in focus simultaneously?

What is the nature of the tapetal reflection?

What is the nature of the tapetal reflection?

Are there focal areas of unusual colouration?

Are there focal areas of unusual colouration?

What is the character of the retinal vessels?

What is the character of the retinal vessels?

What is the appearance of the optic disc?

What is the appearance of the optic disc?

Choroid

The choroid responds in disease by thinning or thickening. The only common instance of choroidal thinning is the change that accompanies collie eye anomaly. Because the uvea is the vascular coat of the eye, choroidal thickening usually accompanies inflammation. In the tapetal fundus, severe choroidal disease is manifest ophthalmoscopically by tapetal discoloration and hyporeflectivity. In unusually severe cases, the inflammatory process may result in subretinal exudation and secondary retinal detachment.

Tapetum

Specific disorders of the tapetum are rare. The most common variations are due to changes in reflectivity. Diminished reflectivity usually occurs with active inflammatory disease (oedema, exudation, retinal detachment). Increased reflectivity suggests thinning/degeneration of the overlying retina. The decreased light absorption that accompanies retinal degeneration allows more light to be reflected back to the examiner from the tapetal surface.

Retina

In very basic terms, the sensory retina can respond pathologically by becoming either thinned or thickened. The effect on the fundus is hyper- or hyporeflectivity, respectively. Retinal thinning invariably represents degeneration of the retina's cellular components, and may follow inflammatory, toxic and ischaemic disease processes. The retina thickens when its layers are folded, as occurs in developmental disorders, or it may swell due to an influx of inflammatory cells, tumour cells or fluid.

The sensory retina also responds pathologically by separating between its sensory and pigmented epithelial layers, a phenomenon referred to as retinal detachment. Detachment can occur secondary to almost any ocular disease. Most often, the effect is hyporeflectivity in the area of the detachment, along with anterior displacement of the retinal vessels.

Ophthalmoscopic changes in the RPE are generally limited to those affecting pigmentation. Increases or decreases in pigmentation are seen in hereditary retinal degenerations and secondary to inflammatory disease processes. Because the RPE is not normally visible in the tapetal region, degenerative changes in that region will not be observed unless they are severe enough to induce secondary changes in the overlying sensory retina. Decreases in RPE pigmentation are readily seen in the non-tapetal fundus.

Retinal blood vessels respond most commonly by a change in size. The differential diagnosis for attenuated retinal vessels includes anaemia, hypovolaemia and retinal degeneration. It is necessary to rely on other clinical signs to make the distinction. Vascular enlargement is less common but is seen in cases of hyperviscosity, polycythaemia, hypertension and inflammatory diseases. Retinal vessels also respond by haemorrhaging or changing colour. Common causes of retinal haemorrhage include anaemia, clotting disorders and hypertension. Retinal vessels appear pink in hyperlipaemic animals or deeper red in hypoxic states.

Optic Disc

In simplistic terms, the optic nerve head responds by becoming too small or too large. These changes may be either congenital or acquired, and their causes are numerous. Congenital hypoplasia or acquired optic atrophy following inflammatory disease, trauma or retinal degeneration will reduce the size of the disc. An enlarged disc accompanies inflammation, neoplasia or oedema.