Royal (Dick) School of Veterinary Studies, The University of Edinburgh, Hospital for Small Animals, Easter Bush Veterinary Centre

Roslin, Midlothian

Causes

Chronic post-viral rhinitis/idiopathic chronic rhinitis

Chronic post-viral rhinitis/idiopathic chronic rhinitis

Chronic bacterial rhinitis

Chronic bacterial rhinitis

Fungal rhinitis

Fungal rhinitis

Allergic rhinitis

Allergic rhinitis

Nasopharyngeal polyps

Nasopharyngeal polyps

Nasonasal polyps

Nasonasal polyps

Nasopharyngeal stenosis

Nasopharyngeal stenosis

Neoplasia

Neoplasia

Foreign body

Foreign body

Trauma

Trauma

Dental disease

Dental disease

Congenital defects

Congenital defects

Laryngeal--paralysis/trauma/oedema/polyp/ granulomata/neoplasia

Laryngeal--paralysis/trauma/oedema/polyp/ granulomata/neoplasia

Diagnosis

Diagnosis of upper respiratory tract (URT) disease, as with all diagnostic investigations, relies on a combination of knowing the signalment of the patient (i.e., its age, sex and breed), gaining a complete medical history, performing a thorough physical examination and then undertaking selected further investigations.

The signalment can be of help since congenital detects will usually cause clinical signs within a few days of birth. However, cat 'flu' is seen most frequently in older kittens, and neoplasia is seen most typically in old cats. While the breed rarely has a bearing on URT disease, the author has seen nasonasal polyps most frequently in oriental breeds of cat.

From the history it is important to determine:

What type of environment the cat lives in

What type of environment the cat lives in

What other animals it lives with

What other animals it lives with

Where it has previously lived

Where it has previously lived

Whether or not it has been vaccinated, and if so, with what

Whether or not it has been vaccinated, and if so, with what

Whether there is any history of previous illness, facial trauma, dental disease or ear infections

Whether there is any history of previous illness, facial trauma, dental disease or ear infections

At what age signs of URT developed

At what age signs of URT developed

What was the pattern of onset of clinical signs

What was the pattern of onset of clinical signs

Were other animals from the same household affected

Were other animals from the same household affected

Did the cat ever have cat 'flu' (remember--chronic post-viral rhinitis is the most common cause of chronic URT disease)

Did the cat ever have cat 'flu' (remember--chronic post-viral rhinitis is the most common cause of chronic URT disease)

How has the disease progressed

How has the disease progressed

Have the clinical signs ever responded to previous treatments

Have the clinical signs ever responded to previous treatments

Is there a history of dysphagia or dysphonia

Is there a history of dysphagia or dysphonia

Physical Examination

The main signs of URT disease are sneezing, nasal discharge and difficulty in breathing. The exact nature of the discharge, whether both sides of the nose are affected, and the presence of other clinical signs are dependent on the nature of the underlying disease, and on the presence of any other illness the cat may have.

Particular points to look out for include:

The presence of nasal discharge, and whether it is bilateral or unilateral.

The presence of nasal discharge, and whether it is bilateral or unilateral.

The character of breathing, and whether or not the breathing is noisy when the cat breathes through its mouth, may help to localise disease to the nasal area or the larynx. Both nostrils should be checked for deformity, obvious obstruction and presence of airflow. Dysphonia may be associated with laryngeal disease.

The character of breathing, and whether or not the breathing is noisy when the cat breathes through its mouth, may help to localise disease to the nasal area or the larynx. Both nostrils should be checked for deformity, obvious obstruction and presence of airflow. Dysphonia may be associated with laryngeal disease.

Facial examination may reveal a lack of symmetry or facial swelling (most typically associated with neoplasia or fungal infections). In Siamese cats the facial hair overlying the inflamed nasal chambers may become de-pigmented.

Facial examination may reveal a lack of symmetry or facial swelling (most typically associated with neoplasia or fungal infections). In Siamese cats the facial hair overlying the inflamed nasal chambers may become de-pigmented.

Ocular examination should involve assessment of the periocular area, the anterior and posterior chambers and the retina.

Ocular examination should involve assessment of the periocular area, the anterior and posterior chambers and the retina.

Aural examination may reveal evidence of painful or infected ears associated with inflammatory polyps.

Aural examination may reveal evidence of painful or infected ears associated with inflammatory polyps.

General body condition and body weight. Cats with URT obstruction often have a poor appetite and so experience a degree of weight loss.

General body condition and body weight. Cats with URT obstruction often have a poor appetite and so experience a degree of weight loss.

Cats with chronic URT disease frequently have mild to moderate submandibular lymphadenopathy. If submandibular lymphadenopathy is marked, or if lymph nodes elsewhere in the body are also affected, neoplasia, mycobacteriosis or fungal infections are most likely to be the cause.

Cats with chronic URT disease frequently have mild to moderate submandibular lymphadenopathy. If submandibular lymphadenopathy is marked, or if lymph nodes elsewhere in the body are also affected, neoplasia, mycobacteriosis or fungal infections are most likely to be the cause.

Kidneys should be assessed for size and shape since nasal lymphosarcoma (LSA) may be associated with renal LSA.

Kidneys should be assessed for size and shape since nasal lymphosarcoma (LSA) may be associated with renal LSA.

Further Investigations

Assessment of serum biochemistry, haematology and feline immunodeficiency virus (FIV) and feline leukaemia virus (FeLV) status will help to gain an overall picture of the cat's health.

Attempts to make a diagnosis from nasal swabs taken from a conscious cat are rarely successful (unless Cryptococcus neoformans is detected). If C. neoformans is detected its presence should be confirmed by culture and/or serology. Bacteria detected in this manner usually represent only secondary contaminants.

The detection of feline herpesvirus 1 (FHV-1) or feline calicivirus (FCV) by oropharyngeal swab and viral culture is rarely helpful. Vaccinated cats and cats that have been previously infected with FCV may also be shedding virus. Since FHV-1 is shed only intermittently, failure of its detection does not negate against it playing a causal role in disease.

It is usually only by performing a detailed examination of the URT (for which the cat has to be anaesthetised), taking radiographs (computed tomography (CT) or possibly magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) investigation) and collecting samples for microbiological and histopathological examination, that a definitive diagnosis may be made. These procedures are performed under general anaesthesia; anaesthesia is induced, the mouth and larynx are examined as the cat is intubated, radiographs are made, and then the nasopharynx and nasal chambers are examined. The investigations can be performed under the same anaesthetic. Radiographs, or any advanced imaging, should be taken before the introduction of flushing solutions, an endoscope or biopsy instruments, since these procedures may result in haemorrhage that will alter the radiographic appearance.

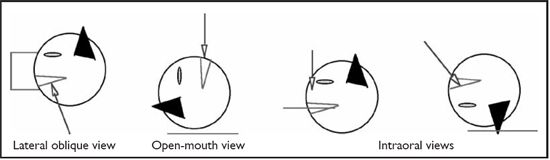

Radiographic investigations should include (Figure 1):

Whole skull radiographs (lateral and ventro-dorsal (VD) views)--to assess the overall structure of the skull, the frontal sinuses, the size and content of the pharynx, etc.

Whole skull radiographs (lateral and ventro-dorsal (VD) views)--to assess the overall structure of the skull, the frontal sinuses, the size and content of the pharynx, etc.

Intraoral view--to assess the nasal chambers and the maxillary dental arcade

Intraoral view--to assess the nasal chambers and the maxillary dental arcade

Open-mouth view--to assess the tympanic bullae

Open-mouth view--to assess the tympanic bullae

Lateral oblique views--to look for the presence of dental disease and to highlight the tympanic bulla

Lateral oblique views--to look for the presence of dental disease and to highlight the tympanic bulla

Radiographs should be assessed for the presence of dental disease, evidence of middle ear infection, obstruction of the nasopharynx by soft tissue, soft tissue density within the frontal sinuses, loss of integrity of the nasal septum and loss of turbinate detail. Whether the loss of turbinate detail is unilateral or bilateral, and its position within the nasal chambers, may help to localise the disease. The loss of turbinate detail may be due to an overall loss of turbinate bone, or an overlying increase in soft tissue. While the nature of the change should be assessed, it is rarely specific. An overall loss of turbinate bone may be seen with chronic destructive post-viral rhinitis, neoplasia, a focal reaction to a foreign body, or fungal rhinitis. An overlying increase in soft tissue may be seen with chronic post-viral rhinitis, neoplasia, nasonasal polyps and allergic rhinitis.

| Figure 1. Radiographic views. |

|

|

| |

Further Physical Examination

Teeth, hard palate, soft palate, oropharynx and tonsils. The teeth, hard and soft palates, oropharynx and tonsils are examined visually and digitally for signs of disease.

Teeth, hard palate, soft palate, oropharynx and tonsils. The teeth, hard and soft palates, oropharynx and tonsils are examined visually and digitally for signs of disease.

The nasopharynx. The caudal nasopharynx is then examined using a dental mirror and a bright light, or a retroflexed bronchoscope.

The nasopharynx. The caudal nasopharynx is then examined using a dental mirror and a bright light, or a retroflexed bronchoscope.

The rostral nasal chambers. Prior to investigating the nasal chambers it is important to pack the caudal oropharynx with surgical swabs. A narrow rigid rhinoscope/arthroscope is more suitable, and in large cats may even permit biopsies to be performed with endoscope guidance. When either using a rhinoscope or taking blind biopsy specimens it is important that the instrument is measured against the animal's face, and marked with a tape tag at the distance from the tip of the nose to the medial canthus of the eye on the same side. This prevents iatrogenic damage to the brain when the instrument is introduced into the nose.

The rostral nasal chambers. Prior to investigating the nasal chambers it is important to pack the caudal oropharynx with surgical swabs. A narrow rigid rhinoscope/arthroscope is more suitable, and in large cats may even permit biopsies to be performed with endoscope guidance. When either using a rhinoscope or taking blind biopsy specimens it is important that the instrument is measured against the animal's face, and marked with a tape tag at the distance from the tip of the nose to the medial canthus of the eye on the same side. This prevents iatrogenic damage to the brain when the instrument is introduced into the nose.

Sample Collection

Samples for cytological and microbiological examination can be collected by a number of methods. Pros and cons exist for each of the methods.

Direct swabs. While direct nasal or pharyngeal swabs are non-invasive they rarely yield useful information.

Direct swabs. While direct nasal or pharyngeal swabs are non-invasive they rarely yield useful information.

Direct aspirates/flushes. Flushing sterile saline through the nasal chambers may help to clear away mucus and debris, and the resultant flush can be used for analysis. Unfortunately, analysis of this fluid is likely to detect only surface contaminants.

Direct aspirates/flushes. Flushing sterile saline through the nasal chambers may help to clear away mucus and debris, and the resultant flush can be used for analysis. Unfortunately, analysis of this fluid is likely to detect only surface contaminants.

Traumatic flush. A traumatic flush entails scarification of the intranasal mucosa at the same time as flushing the nose with saline. While the cellular yield is increased using this technique, the cellular detail is generally poor and the risk of haemorrhage considerable.

Traumatic flush. A traumatic flush entails scarification of the intranasal mucosa at the same time as flushing the nose with saline. While the cellular yield is increased using this technique, the cellular detail is generally poor and the risk of haemorrhage considerable.

Forced flush. A forced flush is performed after firmly packing the caudal pharynx, then forcing approximately 10 ml of saline up one nostril while holding the other nostril shut. This technique can be used to dislodge foreign bodies, inspissated pus, necrotic debris and, occasionally, tumours or polyps. The solid tissue collects on the pharyngeal swabs. The procedure should be performed carefully, as excessive force may flush material through the cribriform place if it has already been damaged by local pathology.

Forced flush. A forced flush is performed after firmly packing the caudal pharynx, then forcing approximately 10 ml of saline up one nostril while holding the other nostril shut. This technique can be used to dislodge foreign bodies, inspissated pus, necrotic debris and, occasionally, tumours or polyps. The solid tissue collects on the pharyngeal swabs. The procedure should be performed carefully, as excessive force may flush material through the cribriform place if it has already been damaged by local pathology.

Pinch biopsies. Pinch biopsies are most easily performed using endoscopic biopsy grabs. Only in very large cats can the biopsies be endoscopically guided. Blind biopsies are usually adequate, provided that two to three samples are collected from each side of the nose.

Pinch biopsies. Pinch biopsies are most easily performed using endoscopic biopsy grabs. Only in very large cats can the biopsies be endoscopically guided. Blind biopsies are usually adequate, provided that two to three samples are collected from each side of the nose.

Nasal core biopsy. Nasal core biopsies can be collected by cutting down a 16 gauge over-the-needle intravenous catheter, and using it like an 'apple corer' to collect a nasal biopsy.

Nasal core biopsy. Nasal core biopsies can be collected by cutting down a 16 gauge over-the-needle intravenous catheter, and using it like an 'apple corer' to collect a nasal biopsy.

Surgery. The most representative and diagnostic biopsies will be gained during surgical exploration of the nose.

Surgery. The most representative and diagnostic biopsies will be gained during surgical exploration of the nose.

While many methods of sample collection have been devised it is important to remember that the larger the biopsy sample, the better the chance of an accurate diagnosis, but the greater the risk of haemorrhage. Since nasal investigations frequently result in bleeding it is strongly recommended that all patients have their clotting times checked prior to beginning the procedure. If intraoperative haemorrhage does occur the intranasal instillation of ice-cold saline or adrenaline may help, along with packing of the pharynx and closing the nostrils.

Unfortunately, the collection of suitable samples does not always lead to a definitive diagnosis. Since most cases of chronic URT disease result from chronic post-viral damage, many of the tests will give negative or non-specific results, at best confirming the presence of chronic active inflammation. A diagnosis of chronic post-viral rhinitis is usually a diagnosis of exclusion.

Treatment

Where a specific disease is diagnosed, specific treatment should be given:

Nasopharyngeal polyps can be removed by gentle traction, pulling the polyp towards the oropharynx. To reduce the risk of recurrence inflammatory material can also be removed from the middle ear. This is usually achieved via an ipsilateral ventral bulla osteotomy.

Nasopharyngeal polyps can be removed by gentle traction, pulling the polyp towards the oropharynx. To reduce the risk of recurrence inflammatory material can also be removed from the middle ear. This is usually achieved via an ipsilateral ventral bulla osteotomy.

Nasonasal polyps can be surgically resected, as can the inflammatory membrane of nasopharyngeal stenosis.

Nasonasal polyps can be surgically resected, as can the inflammatory membrane of nasopharyngeal stenosis.

Foreign bodies can be removed. Local infection can be reduced by curettage. Following foreign body removal, especially where local damage is extensive, a long course of antibiotics is recommended.

Foreign bodies can be removed. Local infection can be reduced by curettage. Following foreign body removal, especially where local damage is extensive, a long course of antibiotics is recommended.

Fungal rhinitis should be treated with antifungal drugs (e.g., itraconazole, fluconazole, ketoconazole).

Fungal rhinitis should be treated with antifungal drugs (e.g., itraconazole, fluconazole, ketoconazole).

Laryngeal paralysis can be ameliorated by performing a unilateral 'laryngeal tie-back'. Any underlying cause should be corrected.

Laryngeal paralysis can be ameliorated by performing a unilateral 'laryngeal tie-back'. Any underlying cause should be corrected.

Post-viral rhinitis/idiopathic rhinitis is rarely curable. The emphasis is on management not cure.

Post-viral rhinitis/idiopathic rhinitis is rarely curable. The emphasis is on management not cure.

Antibiotics. While antibiotics rarely result in a cure, their strategic or long-term use can reduce the severity of clinical signs, and so improve the cat's quality of life. A good response is sometimes gained using a long course of antibiotics (6-8 weeks), starting immediately following intranasal investigations. Recently findings suggest that a long course of doxycycline or azithromycin may be particularly good choices.

Antibiotics. While antibiotics rarely result in a cure, their strategic or long-term use can reduce the severity of clinical signs, and so improve the cat's quality of life. A good response is sometimes gained using a long course of antibiotics (6-8 weeks), starting immediately following intranasal investigations. Recently findings suggest that a long course of doxycycline or azithromycin may be particularly good choices.

Anti-inflammatory agents. While safety is an issue, recent studies have suggested that meloxicam (or perhaps piroxicam) may be particularly good choices.

Anti-inflammatory agents. While safety is an issue, recent studies have suggested that meloxicam (or perhaps piroxicam) may be particularly good choices.

Inhaled corticosteroids. These can help in the general reduction of inflammation, and can be particularly useful in cases of allergic rhinitis (contact author for more information).

Inhaled corticosteroids. These can help in the general reduction of inflammation, and can be particularly useful in cases of allergic rhinitis (contact author for more information).

Leukotriene receptor antagonists, e.g., Zafirlukast or Montelukast. No published trials on the use of this type of drug in cats with chronic URT disease have been published. While it has been suggested that they may help in some cases it is not licensed and not without potential risk.

Leukotriene receptor antagonists, e.g., Zafirlukast or Montelukast. No published trials on the use of this type of drug in cats with chronic URT disease have been published. While it has been suggested that they may help in some cases it is not licensed and not without potential risk.

Therapeutic flush. A therapeutic flush entails adding an antibiotic, antiseptic or other therapeutic agent (e.g., interferon) to the intranasal flush. This can have beneficial effects when performed at the end of a nasal investigation.

Therapeutic flush. A therapeutic flush entails adding an antibiotic, antiseptic or other therapeutic agent (e.g., interferon) to the intranasal flush. This can have beneficial effects when performed at the end of a nasal investigation.

Nasal curettage. While this procedure results in a degree of improvement in some cases, other cases benefit little. Also, the procedure is not without risk, and can be very painful. This procedure should not be undertaken lightly and postoperative analgesics are essential.

Nasal curettage. While this procedure results in a degree of improvement in some cases, other cases benefit little. Also, the procedure is not without risk, and can be very painful. This procedure should not be undertaken lightly and postoperative analgesics are essential.

Frontal sinus ablation, trephination and irrigation. These procedures may be considered where inflammation has extended into the frontal sinuses.

Frontal sinus ablation, trephination and irrigation. These procedures may be considered where inflammation has extended into the frontal sinuses.

Response to these procedures is not always favourable and postoperatively the cat can be in considerable pain. Analgesics are essential