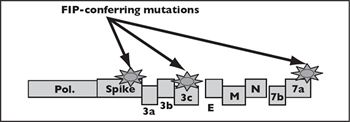

Feline infectious peritonitis (FIP) is a fatal disease of cats caused by infection with a mutant feline enteric coronavirus (FECV). Coronaviruses are large positive-strand RNA viruses with high rates of mutation. Coronaviruses have a tropism for epithelium and interact with host cells via antigens on the surface. On electron micrographs, coronaviruses have little rays extending out from the surface, thus the 'corona'. The main proteins coded for are the spike, M and N membrane proteins, the polymerase and several apparently non-translated open-reading frames designated 3a, 3b, 3c, 7a and 7b.

FECVs are common in multicat households. They are spread by the faecal-oral route, infect intestinal epithelium and are minimally pathogenic. Some infections can cause villus epithelium damage (atrophy, fusion, sloughing and hyperplasia during recovery), vomiting and diarrhoea. Kittens are often infected by the time they are 12 weeks old and produce circulating immunoglobulin (Ig) G.

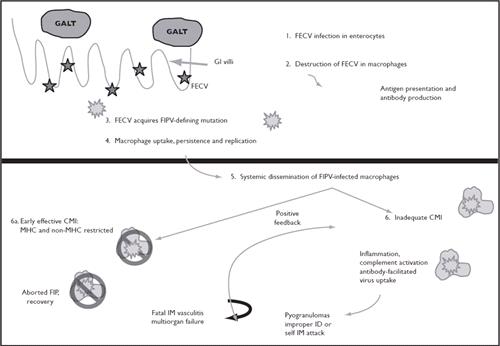

There is tremendous strain variability in feline coronaviruses. Frequently, mutations occur during FECV infection. Mutations have been detected in the 3c, 7b and spike, compared to parental FECV strains, that resulted in changed phenotype and ultimately FIP (Figure 1). FECV is usually not culturable in tissue culture, and replicates in intestinal epithelium, but FIP viruses (FIPVs) usually are culturable is tissue culture. In cats, these mutated viruses acquire the capability to infect and replicate within feline macrophages (Figure 2). FIP is actually an immune-mediated, type III hyper sensitivity reaction by the cat to the infection, in which immune complexes are formed and immuno logical reactions lead to vasculitis and the characteristic pathological and clinical abnormalities. Infection of the macrophage and the feline response result in complement activation, deposition of complement (C) 3, disseminated intravascular coagulopathy vessel necrosis, and effusions. Cytokines become significantly dysregulated in FIP.

| Figure 1 |

M = Matrix; N = Nucleocapsid; Pol. = Polymerase. |

|

| |

Click on the image to see a larger view.

| Figure 2 |

Pathogenesis of FECV (Feline Enteric Coronavirus) infection

CMI = Cell-mediated immunity; FIP = Feline infectious peritonitis; GALT = Gut associated lymphoid tissue; GI = Gastrointestinal; ID = Identification; IM = Immune-mediated; MHC = Major histocompatibility complex. |

|

| |

Cats with FIP often are from multicat households or shelters, from 0.6 to 2 years old (peak mortality at 9.8 months), thin, with or without abdominal effusion, and febrile. Cases are slightly seasonal (fall and winter) and there appears to be a genetic predisposition. Things that are not positive risk factors for FIP are sex, coronavirus antibody titre or coincidental disease. The most common signs of FIP in young cats are cyclic, nonantibiotic-responsive fever, lethargy and failure to grow. Complete blood count abnormalities include elevated total protein (mainly globulin), increased numbers of total white blood cells and neutrophils and decreased numbers of lymphocytes.

In 'dry' or non-effusive FIP, granulomatous masses form on kidneys, mesenteric lymph nodes, liver, spleen and/or in the brain and eyes, and may lead to organ failure. Cats with dry FIP may have weight loss and abdominal abnormalities (lymphadenopathy, palpable changes on liver, spleen or kidneys). Ocular abnormalities include anterior uveitis, anisocoria, keratic precipitates and retinitis. Cats with neurological FIP may have ataxia, hyperreflexia, reduced caudal proprioception, seizures, paresis, dementia and abnormal behaviours. Biopsy specimens of masses in cats with dry FIP show granulomatous inflammation. Cats with 'wet' FIP develop a yellow fluid with high protein content in their chest or abdomen, causing dyspnoea or abdominal distention. The fluid in wet FIP is characteristically yellowish, sticky or mucinous, high in protein and contains neutrophils and macrophages.

Treatment in FIP is palliative. Standard nursing, maintaining hydration and appetite, and broad-spectrum antibiotics are helpful. Additionally, because FIP is immune-mediated, drugs such as immunosuppressive prednisone (4 mg/kg q12h) and cyclophosphamide have been used. One drug that has been proposed is pentoxifylline, which has been used in human immune-mediated vasculitis. This drug opposes tumour necrosis factor (TNF)-α (and some effects of platelet-derived growth factor), improves circulation (by a poorly understood mechanism), reduces collagen production and scarring and reduces neutrophil oxidative damage and phagocytic capability. This is good because some of the typical effects of TNF are pro-inflammatory, manifest clinically as weight loss, fever, etc. Side effects of pentoxifylline are tremor, dizziness, nausea and vomiting. Other immunomodulatory possibilities that require additional exploration include recombinant human interferon (IFN)-α and feline IFN-β.

The diagnosis and management of FIP is difficult but the most important reality about diagnosing FIP is that there is only one way to confirm a diagnosis of FIP: that is to identify the virus in tissue, either on biopsy or at necropsy. Virus can be detected in formalin-fixed tissue by immunohistochemistry on biopsy or necropsy tissues. An 'N' gene immunohistochemical stain is available at University College Davis, USA or monoclonal immunohistochemistry is available at Cornell University, USA.

It is a serious mistake to rely on serology for diagnosing FIP. There is total antigenic cross-reactivity between FECV and FIPV and cats infected with FECV produce antibodies that cross-react with FIPV. Rising titres are not informative, because cats with FIP and FECV cycle both up and down in titre level. Very high titres (>1:16,000) are suggestive of FIP but the severity of disease is not correlated at all with titre. There is no minimum value of titre to rule-out FIP and immunofluorescence antibody tests and enzyme-linked immunosorbent assays (ELISAs) are equivalently sensitive and specific. A '7b ELISA' test is based on the premise that overproduction of 7b protein occurs in mutant (FIPV) strains, which it may in some but certainly not all FIPV mutants.

Polymerase chain reaction (PCR) tests have been developed for FIP and can be useful in the study of disease pathogenesis and diagnosis, but there are critically important limitations. PCR cannot differentiate the FIPV from the FECV because there is no one site among all the possible mutants for PCR primers to attach, thus PCR is performed in conserved regions of the viral genome. Moreover, PCR may be positive in blood, mesenteric lymph node and faeces of a completely healthy cat infected with FECV or negative in a cat with FIP. But the most important caution for using all of these tests is that euthanasia is only warranted if clinical signs suggest FIP, never in a healthy cat based on diagnostic test results alone (except histology).

In natural situations PCR of faeces documents that kittens can be infected with FECV as early as 4 weeks old and show no clinical signs. If kept by themselves, most infected cats can eliminate the infection in 2-3 months but they are immediately susceptible to reinfection and often are reinfected from their housemates. Infected cats shed coronavirus in their faeces intermittently: 20% of pedigree cats are chronic shedders. In multicat groups, 40-60% of the cats shed virus in their faeces at any given time and virtually all cats are FECV seropositive. The prevalence of FECV is 100% antibody-positive in catteries and shelters (with six or more cats), with 41% shedding infectious virus. In feral cat colonies, 10-30% of cats are antibody positive. The major risk factor for shedding FECV is being a kitten.

A few strategies have been proposed that have similar intentions: to minimise FECV. One is quarantine of incoming cats. The only reason to quarantine for control of FECV is if the population into which the cat is being introduced is FECV-negative (i.e., consisting of four or fewer cats that have been isolated from other cats likely for years). And, even if your home was FECV negative, if you bring in an FECV-shedding cat and quarantine it in your bathroom, there is an extraordinarily high likelihood that you will serve as a fomite and infect your other cats. Coronavirus is carried by actively infected cats, chronic asymptomatic shedders and on caretaker's clothes. Quarantine has been effective primarily in research facilities with separate buildings, shower in/out facilities and 100% sero- and PCR-negative populations.

Early weaning is based on the premise that kittens can be removed from infectious queens before they acquire the virus. Certainly kittens have some protection derived from maternal immunity, but kittens as young as 4 weeks have been shown to shed FECV in their faeces. Clearly, routinely removing 3-week-old kittens from queens is difficult for owners and cats. Moreover, there is a very high probability that kittens kept anywhere in the house where there are adult, FECV-infected cats will acquire infection via fomites within a few weeks anyway. Finally, depopulation of a cattery is effective but impractical and probably counterproductive.

There are a few recommendations shelters and breeders can implement to minimise FECV and FIPV. Most important is to screen routinely for FIP through veterinary examinations and potentially tests during routine surveillance that could highlight cats that are early in the course of FIP. Such tests could include coronavirus antibody titres, evaluation of serum proteins, complete blood counts and abdominal palpation. If results suggest reason for concern, additional investigation of FIP might include radiography, ultrasonography, or simply follow-up every several months. Any cats leaving the group for adoption, sales, etc. should be accompanied by information about FIP and any test results that are available for the adopted or sold cat. Identification of chronic shedders would be helpful but typically impractical. Keeping cat (and especially kitten) populations to a minimum is extremely helpful.

References

1. Foley JE, Poland A, et al. Patterns of feline coronavirus infection and fecal shedding from cats in multiple-cat environments. Journal of the American Veterinary Medical Association 1997; 210:1307-1312.