Ralf S. Mueller, MAVSc, DACVD, FACVSc, DECVD, DrMedVet, DrHabil, FAAAAI

Immune-mediated skin diseases come in many varieties with varied clinical signs. However, there are some clinical or historical clues that make these diseases more likely and should lead to a more aggressive diagnostic work-up early on in the disease. These are listed below:

Historically the disease had an acute onset and the patient rapidly deteriorates

Historically the disease had an acute onset and the patient rapidly deteriorates

Mucous membranes or mucocutaneous junctions are affected

Mucous membranes or mucocutaneous junctions are affected

Skin lesions are only part of the disease and other organ systems seem to be involved (joints, kidney, etc.)

Skin lesions are only part of the disease and other organ systems seem to be involved (joints, kidney, etc.)

The nasal planum is affected

The nasal planum is affected

Cytology may be useful in the diagnosis of diseases of the pemphigus complex. An impression smear is most commonly used. The slide is gently pressed against an eroded, exudative or ulcerated area (if none is present, one can carefully peel off a crust and sample the eroded surface underneath) and stained with DiffQuick. In many patients with pemphigus, so-called acantholytic cells will be identified. These cells are keratinocytes that stain blue to purple, are round and have a central nucleus. They are not diagnostic for pemphigus (as occasionally they can be found in pyoderma as well), but indicate a need for a biopsy and a probability of pemphigus.

When should we perform a skin biopsy because we suspect immune-mediated disease?

Any skin lesion which appears unusual to the clinician should have a biopsy performed

Any skin lesion which appears unusual to the clinician should have a biopsy performed

If an immune-mediated disease is on the list of differential diagnoses, a biopsy is indicated

If an immune-mediated disease is on the list of differential diagnoses, a biopsy is indicated

A biopsy should also be considered if lesions fail to respond to empirical therapy

A biopsy should also be considered if lesions fail to respond to empirical therapy

There are several immune-mediated skin diseases that may occur in veterinary dermatology, but most of these are extremely rare and seen once in a lifetime of a general practitioner, if that. However, dogs and cats with discoid lupus erythematosus or pemphigus foliaceus are presented infrequently but regularly in small animal practice and we will focus predominantly on these two diseases.

Pemphigus

The pemphigus complex includes several subtypes in all of which the immune system for various and often unknown reasons starts to produce antibodies against parts of the desmosomes, the little connections holding adjacent keratinocytes together. These (auto-) antibodies are called pemphigus antibodies.

The antibodies in the different subtypes are directed against different antigens of the desmosomes expressed in different layers of the epidermis. Thus, the location of the forming vesicles within the epidermis and the resultant clinical signs vary.

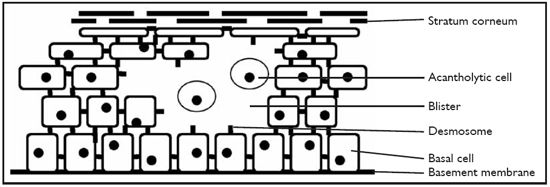

Once the antibody is bound to the part of the desmosome which forms the antigen, the complex is 'swallowed' by the cell and elicits intracellular reactions leading to the release of plasminogen activator. The subsequent plasminogen activation results in the production of plasmin, a protease that destroys the desmosomes and leads to acantholysis (the process, where keratinocytes lose their intercellular bridges and 'round up'). These acantholytic cells are located as single cells in vesicles formed by the destruction of the intercellular connections (Figure 1).

| Figure 1. Schematic picture of an intraepidermal blister caused by acantholysis. |

|

|

| |

In the case of pemphigus vulgaris the blisters are located suprabasally (which means that the basal keratinocytes are still attached to the basement membrane but the rest of the epidermis lifts off). As you can imagine, such deep vesicles rapidly develop into ulcers once burst. Pemphigus foliaceus and erythematosus develop a split within the spinosal layer or subcorneally. Thus, the blisters are more superficial and erosions and crusting rather than ulceration predominate. Drug reactions can reportedly trigger pemphigus in humans and animals, thus a history of recent drug application (including medications like heartworm pills or deworming agents) should be taken. Some animals will exhibit a worsening of clinical signs upon sun exposure as well.

Clinical Signs

Lesions of pemphigus vulgaris are characteristically seen in the oral cavity (80% of the cases have oral ulcers or vesicles at the time of diagnosis), other mucous membranes and the groin and axillae. Lymphadenopathy, anorexia, lethargy and fever as well as secondary pyoderma (and sepsis) are frequently present. These pets are sick, look disgusting and feel miserable. Pemphigus foliaceus is one of the most common immune-mediated skin diseases. The mean age in a bigger study was 4.2 years. Akitas, Chows and Dobermanns are some of the more commonly affected breeds.

Depigmentation of the nasal planum and/or crusty lesions of the dorsal muzzle, periocular areas and pinnae are often the first signs. Feet, footpads and groin are affected commonly. In some dogs, hyperkeratotic footpads (with occasional sloughing) are the only clinical signs. Generalisation may occur after weeks to months. Pruritus, pain and lethargy may be seen in some cases. Paronychia (with often a caseous, brownish material accumulating in the nail fold) and nipple involvement is frequent in cats. One of the classical clinical clues for pemphigus foliaceus (especially in cats) is crusting on the inside and non-haired center of the pinnae. Pemphigus erythematosus is clinically indistinguishable from early pemphigus foliaceus with facial involvement only.

Diagnosis

Biopsy is the diagnostic test of choice. It is usually performed after skin scrapings have been negative, no evidence of fungi or bacteria has been found on cytology or antibiotic therapy improved the patient, but pustules and crusts without microorganisms are still evident on reexamination.

Multiple biopsies should be performed (the author usually takes four to five samples) and you must choose your sites carefully. Ideally you want to take intact pustules. The second best lesion to biopsy is a papule, a little red bump not yet crusted. And last, you may include some really crusty lesions with the thick crust still attached to the biopsy. Give the pathologist your differential diagnosis list and ask the laboratory to 'please cut the crusts in' as they may contain important clues. In some cases, re-biopsy is necessary as initial samples may be non-diagnostic despite all of the clinician's efforts. On a classic biopsy specimen intraepidermal or subcorneal pustules are filled with neutrophils, acantholytic cells and occasionally eosinophils. More often than not numerous acantholytic cells in the crusts are your only diagnostic clue.

Prognosis

The prognosis for pemphigus foliaceus as well as pemphigus erythematosus is fair, even though life-long immunosuppressive treatment is necessary in most cases. Sometimes partial remission with only few residual crusts is achieved with comparatively low doses of immunosuppressive drugs, and complete remission requires much higher maintenance doses. It may be reasonable and safer for the patient to maintain the disease at partial remission in these particular cases. Pemphigus vulgaris has a guarded to poor prognosis.

Discoid Lupus Erythematosus

Discoid lupus erythematosus (DLE) is one of the more frequently encountered autoimmune skin diseases in dogs and humans and has been reported in cats. The exact pathogenesis of DLE is not elucidated in dogs and cats. However, a subset of dogs with clinical signs definitely deteriorates when exposed to ultraviolet (UV) light and improves on UV protection, thus it is safe to assume that UV rays play a role in at least some of the patients with DLE. Another subset of animals does not seem to be influenced at all by changes in UV exposure. Breed predispositions exist for Collies, Shetland Sheepdogs, German Short-haired Pointers, Siberian Huskies and Brittany Spaniels.

Clinical Signs

Discoid lupus erythematosus in early stages is characterized by depigmentation, erythema and scaling of the nose. The rough cobblestone-like architecture of the nasal planum changes into a smooth surface. Depigmentation of the skin around the eyes and the lips is observed less commonly. Erosions, ulceration and crusting are changes occurring later and may extend from the nasal planum and nostrils up to the dorsal and lateral part of the haired muzzle. These changes may be encountered around the eyes as well as on the pinnae. Scarring may occur in severe and chronic cases.

Diagnosis

Biopsy of skin lesions is the diagnostic procedure of choice. You want to choose non-ulcerated lesions, because the site of action, the dermoepidermal junction, is gone as well as the epidermis, if you perform a biopsy on an ulcer. Ideally, a greying area is chosen because the depigmenting is actively going on and the histopathological findings are most diagnostic, while the depigmented areas are already 'burnt out'. For discoid lupus erythematosus two to three punch biopsies are performed. The author typically chooses 6 mm punches for the nose and 8 mm for the dorsal muzzle in most dogs; and 4 mm punches for the nose and 6 mm for the dorsal muzzle in cats and toy breeds. For cutaneous changes on the trunk or legs the author always uses 8 mm punches or excisional biopsies.

References

1. Mueller RS, Krebs I, et al. Pemphigus foliaceus in 91 dogs. Journal of the American Animal Hospital Association 2006; 42: 189-196.

2. Olivry T. A review of autoimmune skin diseases in domestic animals: I--superficial pemphigus. Veterinary Dermatology 2006; 17: 291-305.

3. Wiemelt SP, Goldschmidt MH, et al. A retrospective study comparing the histopathological features and response to treatment in two canine nasal dermatoses, DLE and MCP. Veterinary Dermatology 2004; 15: 341-348.