Dr. Carmen L. Battaglia

Some people live an entire lifetime and wonder if they have ever made a difference in what they are doing. The serous breeder of purebred dogs doesn't have that problem.

Introduction

The term pedigree is an old word which is derived from the French "pied de grue", meaning crane's foot. The drawn pedigree was first used in the breeding of cattle and other domestic livestock. Now, after more than six centuries, the practice of using it as a primary breeding tool continues. Over the years breeders learned that some of the most important uses of a pedigree were to identify the dogs that were carriers along with those that could be counted on to make an improvement. Thus, when the frequency of a trait or disease occurred with regularity among the ancestors, it served as a signal that something is likely to be heritable.

When breeders first began to analyze their pedigrees, two problems caused them to hesitate when selecting stud dogs and brood bitches. The first was the uncertainty of possible health problems; the second was the need for missing information. Some ignored both, which explains why they continued to produce unhealthy puppies as well as others that were of poor quality with nervous characters.

Each time a breeding occurs it should be regarded as another "test breeding" for the benefit of the stud dog owner. In this regard, many breedings use animals that are not related. These breedings only promote more heterozygosity, and usually more variation in the traits that occur in the litters. These are called outcrosses which bring in new genes and traits that the breeding stock does not possess. At the same time, each outcross breeding has the tendency to mask the expression of recessive genes.

Linebreeding concentrates the genes of a specific ancestor or ancestors. These breedings require the careful selection of mates because related individuals are likely to have genes similar to each other. Inbreeding significantly increases homozygosity and therefore increases the chances for uniformity in litters. Inbreeding can be beneficial and detrimental but it will not change or create new genes or undesirable genes. It will only expose those carried by the sire and dam through homozygosity.

Breeders sometimes worry about inbreeding coefficients which are estimates of the percentage of all the variable gene pairs common to the ancestors and are based on several generations of ancestors. Bell reported that inbreeding in the fifth and later generations can have a profound effect on the genetic makeup of the offspring. The difference between inbreeding coefficients in a four versus eight-generation pedigree can be strikingly different. For example, a four-generation pedigree containing 28 unique ancestors for 30 positions in the pedigree could generate a low inbreeding coefficient, while eight generations of the same pedigree, contain 212 unique ancestors out of 510 possible positions and could have a considerably higher inbreeding coefficient. What would appear as an outcross in a couple of generations could be seen as a linebreed concentration of genes from influential ancestors in extended generations.

Many breeders plan matings solely on the appearance of the sire and dam. These breedings are called type breedings which are nothing more than like-to-like matings. While two individuals in two pedigrees (sire and dam) may share desirable characteristics, they may inherit them differently. This is especially true of polygenic traits, such as ear set, bite or length of forearm. Breeding two phenotypically similar but genotypically unrelated individuals together would not necessarily reproduce these traits. Conversely, two individuals with the same pedigree (littermates) will not necessarily look or breed alike. Therefore, matings should be based on the combination of appearance and pedigree analysis.

Some breeders worry about genetic diversity when they linebreed and inbreed. Molecular genetic research shows that for many breeds there is more diversity (heterozygosity) present than breeders might realize. Many believe that line and inbreeding will cause the loss of genes from a breed's gene pool. This is not the case. The loss occurs through selection, meaning the use or non-use of certain individuals. Regardless of the popularity of a stud dog, if a large number of breeders begin to use the same stud, (the popular sire syndrome) the gene pool will drift in that individual's direction and there will be a loss of genetic diversity.

Those who do not collect and code information on their pedigrees about the ancestors and their littermates usually are forced to rely on "type" breeding. This means they select sires and dams based on their appearance rather than on the traits observed in their offspring or the relationship that exists between them. Many times "type" breeding simply means breeding the winners to the winners. In practice, these breedings fail to take advantage of what the science of genetics has taught us about inheritance. Studying a pedigree for its genotypes means focusing attention on the occurrence of traits found among the ancestors and their littermates. Developing a sound breeding program means knowing which pedigree to use based on the information collected about each ancestor.

If you line reed and are not happy with what you produce, breeding to a less related or unrelated individual immediately creates a situation that brings in new traits. Repeated out crossing in an attempt to dilute detrimental recessive genes is not a desirable method because the recessive genes cannot be diluted. They are either present or not. If an individual is a known carrier or a high carrier risk it should be retired from the breeding program and replaced with a quality offspring if one occurs. That offspring can be used as a replacement for one of its parents with the goal of losing some of the defectives gene. This approach to managing the carriers is called breeding-up.

Searching the Genotypes

Researchers and breeders often use the terms phenotype and genotype. Phenotype refers to the characteristics that can be seen, meaning their external appearance. Hence, a dog that is observed to be black (phenotype) may or may not produce only black puppies. It could have a genetic make-up (genotype) that includes the genes for other colors. Since genotypes can not be seen directly, indirect methods must be used to learn about them. Indirect methods are not estimates or guessing games.

Two basic methods are useful when analyzing pedigrees. The first is called depth of pedigree meaning the focus will be on the ancestors in each generation, usually those in the first three to five generations. When a trait or disease occurs among these ancestors it serves as a signal that the trait or disease is likely to be heritable. The second method is called breadth of pedigree, which means that the litter mates of each ancestor will be included in the analysis of the pedigree. Littermates serve as good indicators of the traits or diseases found in their pedigree. This is because they share the same parents and the same gene pool. Both methods help breeders to breed by direction rather then by chance.

Pedigrees

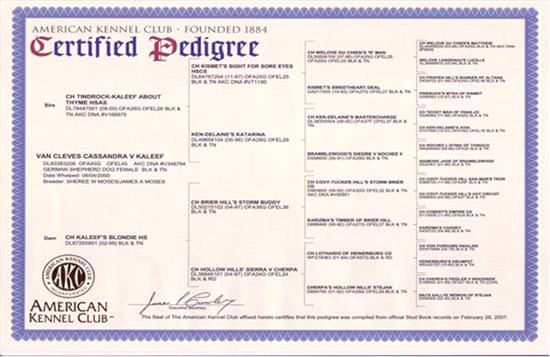

Over the years three kinds of pedigrees have emerged for breeders to use, each with its own special purpose. The first and most popular pedigree is called the Traditional Pedigree. It is the oldest of the pedigrees, but as a breeding tool it has many shortcomings, the most notable of which is the importance it places on memory and knowing the names and titles of the ancestors which are not heritable. Historically breeders have had to rely on their ability to recognize and associate names and titles with the traits and characteristics of each ancestor. This approach, however, lacked reliability, and it did not capture the information needed to plan a breeding. Another problem associated with the Traditional Pedigree involved litter evaluations. When something worked, credit could be given to the pedigree and the breeder. But when it didn't, there was no record or source of information to be reviewed. The major criticism of this pedigree is that it does not lend itself to collecting the right kinds of information in sufficient detail to be useful to plan a breeding. A review of how most Traditional Pedigrees are used show that scribbled notes around the edges and in the margins typically serve as the breeder's record system. Words such as "beautiful coat", "wonderful type", a title or the name of a famous offspring serve as the record breeders have used. This approach fails to collect what is relevant or specific to making improvements. In short, this pedigree does not provide a way to learn from ones mistakes.

Click on the image to see a larger view

| Figure 1 - Traditional Pedigree |

|

|

| |

The advantages to using the Traditional pedigree (Figure 1) are that it is easy to read and requires little training. Unfortunately it does not display information about the carriers, normal or affected ancestors, nor is it clear which ancestor(s) has the desirable and undesirable traits. As a breeding tool it forces breeders to rely on non-heritable information such as titles, certificates, winning records etc. Its best use occurs when a puppy is sold. The breeder can show the buyer all the champions and "famous" ancestors in the pedigree.

Stick Dog Color Chart Pedigree

The second pedigree is called the Stick Dog Color Chart Pedigree. It was developed to focus on the traits of conformation that are described in the breed standard. The Stick Dog Color Pedigree is drawn using stick figures rather than names and titles. The logic underlying this pedigree is to draw each ancestor as a stick figure of coded information.

Coding Traits

Each stick figure is drawn with seven structural parts: ears, head, neck, front, back, rear and tail. Each of these conformation traits is color coded for its quality or lack of quality based on the breed Standard.

Color Codes

In addition to ranking qualities using color-codes, notes are added to clarify the color codes.

Use of Color to Code Traits

|

Ribbons |

Codes |

Rank for Quality |

|

Blue |

Blue |

First place quality based on the breed standard |

|

Red |

Red |

Second place quality based on the breed standard |

|

Yellow |

Yellow |

Third place quality based on the breed standard |

|

White |

Black |

Fourth place quality based on the breed standard |

|

|

Circle |

Missing information |

The rules for coding the quality of a trait or the lack thereof, is straight forward. When a trait is coded with a first place color (blue), it is viewed to be correct or ideal based on the breed standard. For example, if the ears on a sire were coded blue and those on the dam were coded black, the breeder would know that the sire's ears were correct but the ears on the dam were not correct and lacking in some way. Thus, the color-coding of each trait for their quality identifies the specific location of a strength or weakness. Coding stick figures shows trends and problems and whether they occur on the sire or dams side of the pedigree.

| Figure 2 - Stick Dog Pedigree |

|

|

| |

Notice that brood bitch "A" has a fourth place front as does her father, grandfather, and her grandmother on her mother's side. Thus, in just the first two generations, three out of six ancestors, or 50% of her ancestors, all have the same fourth place front. This suggests that she inherits her faulty front legitimately from her ancestors. It should also be noticed that poor fronts occur on both sides of her pedigree. This is useful information when searching for the right stud dog.

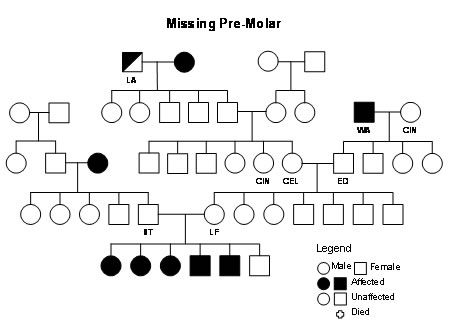

Symbols Pedigree

The third pedigree is called the Symbols Pedigree. It gets its name because symbols rather than names are used to identify each ancestor and their gender. This pedigree is different from the Traditional and Stick Dog Color Dog Pedigree in that its purpose is to track and analyze health, performance and other special traits of interest. The Symbols Pedigree relies on the logic that a pedigree can be understood by learning about the traits and characteristics observed among the littermates of each ancestor.

Coding

The Symbols Pedigree is a powerful tool because of the amount of information that can be collected and coded about each ancestor. Unlike the Stick Dog Color Chart Pedigree, this pedigree uses two symbols. Squares are used to represent the males and circles are used to represent the females. In this way the littermates for each ancestor can be represented as either a circle or a square. As information is collected about each ancestor and their littermate it is coded using designated colors that represent specific traits or diseases. Because breeders are interested in many traits and diseases they will use several colors to code this pedigree. Key words and phrases are also added to clarify and further explain the characteristics, conditions, test results etc. for each ancestor. The repetition of a color, key word or phrase usually signals that a genetic trend or pattern may be present. When an individual is confirmed to be a carrier of a specific trait or disease, its symbol is coded using a dot of the same color that was used to code the presence of that trait or disease. Coding the Symbols pedigree with DNA test information can provide with pin point accuracy about the health status of each individual.

| Figure 3 - The Symbols Pedigree |

|

|

| |

Notice in Figure 3, that the sire of the litter had three sisters and one brother and that the dam had four brothers and two sisters. This pedigree also shows a litter of six pups (3-3). Five of these six pups had missing teeth. In this five generation pedigree the breeder is coding ancestors that have missing teeth. The color black is used to code those that have missing premolars. By identifying and coding all of the ancestors and littermates the breeder will know not only the litter size and gender but also those that are affected. Notice that sire "ST "had three sisters and one brother and that brood bitch "LF" had four brothers and two sisters. Also notice that the breeding of "ST" to "LF" produced a litter of six pups (3-3). Knowing that five of six pups had missing premolars would be reason enough to be cautious about the remaining littermate. If the breeder had not coded the affected and normal pups there would be a high probability that the one pup with full dentition would go unnoticed as a probable carrier for missing teeth. These examples show why coding each ancestor and the littermates are so important, and it demonstrates how differently a breeder would think about using a sire or dam when this kind of detailed information becomes available about the pups that were produced.

A comparison between the quality of information that becomes available when using the Traditional Pedigree versus the Symbols and Stick Dog Color Chart Pedigree should be convincing evidence that the latter two better serve the need of the breeder who intends to use pedigree analysis as a means to making improvements.

References

1. Battaglia, C. L. - Breeding Better Dogs, BEI Publications, Fifth Printing, Atlanta, GA. 1986.

2. Battaglia, C. L. - Genetics - How to Breed Better Dogs, T.F.H., Neptune, NJ, 1978.

3. Bell, Jerold, "Developing a Healthy Breeding Program", Proceedings. National Parent Club Canine Health Conference, AKC Canine Health Foundation, St. Louis MO. October 1999, pg. 15-17.

4. Brackett, Lloyd, C., Planned Breeding, Dog World Magazine, Chicago, Illinois, 1961.

5. Foley, C.W; Lasley, J.F. and Osweiler, G.D., Abnormalities of Companion animals: Analysis of Heritability, Iowa University Press, Ames, Iowa, 1979 McGraw-Hill, 1950, 2nd Ed. New York.

6. Hutt, Fred, Genetics for Dog Breeders, WH Freeman Co., San Francisco, CA, 1979

7. Reif, Jane, "What's in a Pedigree?" American Kennel Club Gazette, New York, New York, August 1994 Vol. 111, N0. 8, Pg 30 - 32.

8. Seranne, Ann, The Joy of Breeding Your Own Show Dog, Howell House, New York, New York, 1984, P 51.

9. Willis, Malcolm, "Breeding Better Dogs ", Key Note Address, Proceedings, National Parent Club Canine Health Conference, AKC Canine Health Foundation, St. Louis, MO., October 1999, pg. 15-17.

10. Willis, Malcolm, Genetics of the Dog, Howell Book House, New York, New York, 1989.