The Andean Dog: Known Breeds and it's Relationship with the South American Man

INTRODUCTION

The idea that the Andean dog was product of the Spanish conquest--here is who thinks that the no dogs existed in America and if it exist it were "wild" and the domestic ones were brought by the Spanish--began to break with the archaeological foundings done in the Andean territory, of dog bony samples as representations of this animal in different materials (ceramic, lithic and metal). Although this foundings were not studied and it showed only the dog presence and not about the relationship they had with man, it was the base to scientific studies(1). The colonial documents and ethnographic data were the beginning for these studies, and then these make contrast with the archaeological data.

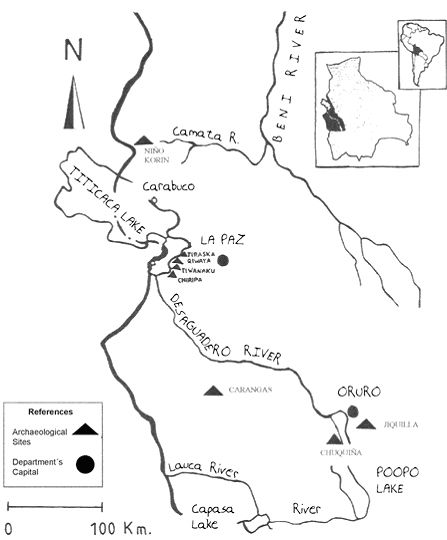

The investigation was done in the high plateau of Bolivia which has a sub-humidity part and an arid part. The sub-humidity part begins in the Titicaca Lake, followed by the Poopo Lake and the Desaguadero River (which is considered to be a semiarid zone) the arid part is desertic and it is formed by the salt deposits (Uyuni, Coipasa and others). The ubication of the archaeological materials and the archaeozoological remains are founded in the North high plateau that is between the Titicaca Lake and the Poopo Lake(2) (Figure 1).

| Figure 1. |

Ubication of the archaeological sites of the north high plateau of Bolivia from which the material of Canis familiaris used in this paper comes. |

|

| |

The results showed that a close relationship between man and dog existed in the Andes, since the Formative period (2 000 B.C.-200 A.D.) to the Inkario (c.a. 1450-1600 A.D.) This relationship is reflected in the different functions that the dog did in the prehispanic times, in the social, religious and economic circles; also the existence of other types of dogs was possible to recognize in the Andean zone, identifying hairless dogs and hairy dogs, and in this last ones existed three kinds. The conclusions of these studies remain in the importance of the dog inside the Andean Weltanschauung.

ANTECEDENTS

In the year 1896 Arthur Posnanky(3) showed in his book "Tiahuanacu. The cradle of American man", the founding of a "mummified dog", which was discovered beside a burial to the Post-Tiwanakua era. Then in 1956, in the center of the city La Paz, Maks Portugal Z., reported the founding of a dog in a burial with human corpses of the Inka epoch. In the 70´s canids bony remains foundings were reported by the archaeologists Browman and Cordero(4), it was also found dog representations in different materials (5); in the 80`s and 90`s archaeologists as Bermann, Manzanilla(6), Lemuz(7) and Paz(8) between others, gave information about the dog's function in the Tiwanaku Culture. For the great part of these foundings the actual ubication is unknown because of the little interest that these animal bones represent for the archaeologists that worked this region. There existed several things--different cultural period presence--the dog in the Andean high plateau, was not known how was the relationship between the Andean societies and their implications, until the "El perro en las sociedades andinas del pasado: un aporte arqueozoologico" (The dog in the past Andean societies: an archaeozoological contribution) (1) was done, work that analyzed and order the archaeological and archaeozoological material available to know the interrelationship man--dog in the Bolivian high plateau.

RESULTS

In the study done a total of 19 archaeological pieces were analyzed: ten bony pieces, three ceramic ones, two lithic ones, two metals, one wood and exceptionally no archaeological material that is a photograph from the year 1896. This material comes from the archaeological sites of: Chiripa, Qiwaya, Santiago de Huata, Tiwanaku, Chuquiña, Tiraska, Jiquilla, Niño Korin and Carangas (Figure 1). Colonial documents were analyzed too, such as the chronicles of the XVII and XVIII century, and the oral history, translated in myths, legends and life experiences of the people who live near the archaeological sites of where the materials come from.

From most part of the bony pieces information was extracted, information with reference of species, age, sex, weight, size, type or form of these specimens, following the determined parameters of Crockford (9) and Valadez (10-13). From the other pieces (no bony ones) this same information was able to take according to the physical characteristics shown. The function determination depended of the context and the taphonomic analysis(14) applied (in bony samples cases). Not all the pieces belong to Canis familiarisb this material gave important results to reach the relationship of dog and Andean societies.

The results, although it were modest (Figure 2) are not meaningless because it let us recognize the morphology of the studied individuals just as its possible uses and so the kind of relationship that the dog had with the Andean man. The details of each case can't be shown in this space, so it was considered better to use it to show the reader the implications of the realized study.

DISCUSSION

Could it be possible that the Biology, Archaeology and History use (oral and written), can join to know how the relationship man--dog was and also to determine the possible types that were their in the different cultural periods in a regional level (North High plateau), to the level we can generalize this results at a South American level?

From here it is done a summary about the dog use and the possible existent breeds in the cultural periods of the Bolivian high plateau.

Formative Period (ca. 2000 B.C., 400 A.D.). An example of the presence of the dog in this period is found in the Chiripa Culture (1500-100 A.D.), which has its place in the circumlacuster area of the Titicaca Lake. This culture conceived the dog as part of the weltanschauung, using it as offerings in different ceremonies. This use took physical place through its representation in sacred objects (tablet, stele). In both cases this animal was used to show the sexual andean duality (male--female) and space (up--down).

Another important example existed in the Wankarani Culture (1800 B.C.--400 A.D.), located around the Poopo Lake, in this case, the data show that the dog was also a part of their weltanschauung, using its representations (clay figures) as companion to the deceased, showing the conception of life after death that still appears in our culture.

In the phase Late Pana (200-300 A.D.) (Santiago de Huata), bony remains existed that show that the dog was used as food (Figure 2).

As the results show, the types of dogs that existed in the Formative were hairy dogs: one medium type, dolicephalic and another of small size, short legs, dolicephalic and mesaticephalic.

Tiwanaku Period (400 B.C.-1200 A.D.). The Tiwanaku culture extended a lot, occupying territories that actually belong to countries as Peru, Bolivia and Chile. This culture Interacted with the dog inside their weltanschauung and was used in animals and its representations. In the religious part, the dog was used as offering in sacred places possibly attached to water; also took the function of companion of the deceased keeping the conception of life after death, in the economic it was of help in the hunting activities, possibly helping to hunt and picking up the prey. The type of dog that we have evidence it had hair, dolicephalic of medium to big size and straighten ears.

Andean Confederations (1200-1470 A.D.). The Andean Confederations period is composed by several cultures, denominated "aymaras dominion", these were placed in the high plateau, occupying actual territories of Peru, Chile and Bolivia. The mayor characteristic of these cultures was its type of burials that were done in funerary towers known as chullpas. Between these cultures Pacajes, Carangas, Mollo, Lupacas; Quillacas, Soras and others are founded. In this period the interrelationship with the dog is obvious, especially as companion of the deceased, inside the andean conception of life after death.

Inside this period we can see the presence of the hairless dog or K´hala (Figures 2 & 3) in which it is dolicephalic, svelte and has only hair in the head, tail and legs, but also it is reported the existence of a braquicephalic dog with fallen ears, with hair; represented in ceremonial objects (Figure 2).

The Inkario (1470-1532 A.D.). The Inkas occupied a big territory that actually is part of Colombia, Ecuador, Argentina, Chile and Bolivia. The archaeological material and the chroniclers' reports indicate that in this period the relationship man-dog existed in the different functions they did, being the most important:

Ritual symbol, from little metal statues that symbolized the andean duality "yanantin"(15), that explains a same sex couple, as the perfect pair. The use of this company is reflected in drawings and reports of the Indian chronicler Felipe Guamal Poma de Ayala (1534-1615) (16, 17) and also the report of Father Bernabé Cobo (1580-1577) (18), that indicates that Indians, although miserable, wanted their dogs more than their own sons, because they carried them and slept together.

Ritual symbol, from little metal statues that symbolized the andean duality "yanantin"(15), that explains a same sex couple, as the perfect pair. The use of this company is reflected in drawings and reports of the Indian chronicler Felipe Guamal Poma de Ayala (1534-1615) (16, 17) and also the report of Father Bernabé Cobo (1580-1577) (18), that indicates that Indians, although miserable, wanted their dogs more than their own sons, because they carried them and slept together.

As helper in hunting activities, its function is represented also in the Poma de Ayala drawings.

As helper in hunting activities, its function is represented also in the Poma de Ayala drawings.

The functions as home and cattle guardian is founded in evidences of the chroniclers reports such as Poma de Ayala and Cobo.

The functions as home and cattle guardian is founded in evidences of the chroniclers reports such as Poma de Ayala and Cobo.

Its use as food is also registered in these chronicles; but the interesting part is that not everyone did this, because it was a condemn activity by the Inkas, although it is shown that the Huancas, Jaujas and Mochicas ate dog.

Its use as food is also registered in these chronicles; but the interesting part is that not everyone did this, because it was a condemn activity by the Inkas, although it is shown that the Huancas, Jaujas and Mochicas ate dog.

The types of dogs we can recognize for the Inkario are very diverse so, we can show: hairy form, braquicephalic with fallen ears, mesaticephalic type, short legs; another with dolicephalic skull, small to big size, straighten ears and at last the hairless dogs or K´halas.

Another important chronicler that gave us information about the prehispanic dog is the Father Ludovico Bertonio, that in his work "Vocabulario Aymara" (Aymara Vocabulary)(19), describes dog's characteristics that have its equivalent in aymara language. In the following part is shown the most relation terms of the dog's physical form:

Dog with big ears that hang a lot = Jinchuliwi

Dog with big ears that hang a lot = Jinchuliwi

Big dog = Pastu

Big dog = Pastu

Very hairy dog = Ch´usi anuqara

Very hairy dog = Ch´usi anuqara

Little dog = Ñañu

Little dog = Ñañu

The facts from other South American regions, specially Peru, are very big, the problem is that they had not been part of studies that wish to comprehend the relation of the dog with the prehispanic andean cultures and its different ways of life, the same thing happened with the breed identification, because there are not studies of these themes in South America, that's why the mistake of affirm that every rest or representation in archaeological material of a dog is K´hala breed or hairless is done, also many peruan investigators affirm that the hairless dog had its origin in Peru; but there are not proofs of that.

Without doubts the study presented here represents the most new about the roll of the dog in the andean zone because although actually frontiers that divide this regions exist, the results shown here can be taken for the higher part of Peru too (mountains).

CONCLUSION

The relationship man-dog in the Andean societies from the past (Formative to Inkario) in the Bolivian north high plateau, were very dynamic, being part of the social, economic and religious sphere. These relationships were very close creating strong attachments which appear in the different functions in the social and economic activities, of course without resting importance to the affection that we see in many of the functions the dog did. These relationships were good for both because the dog in most of the times was sacrificed and we have evidence that it was in its adult age in good condition.

Since the Formative period the dog was very close with man no matter its age, sex, size, type or form, being part of their weltanschauung, also it exists continuity in this conception until the Colony times. About the breeding determination we can say, taking the Bertonio work, the drawings of the chronicler Poma de Ayala and the analysis result of archaeozoological and archaeological material four types of prehispanic dogs in the Andean zone.

Type 1) Jinchuliwi. Braquicephalic dog, hairy, medium size, fallen ears.

Type 1) Jinchuliwi. Braquicephalic dog, hairy, medium size, fallen ears.

Type 2) Pastu. Dolicocephalic dog, hairy little medium and big size, straightens ears; and with long hair it will be C´husi anuqara.

Type 2) Pastu. Dolicocephalic dog, hairy little medium and big size, straightens ears; and with long hair it will be C´husi anuqara.

Type 3) Ñañu. Small dog, short legs, hairy, straightens ears, dolicocephalic.

Type 3) Ñañu. Small dog, short legs, hairy, straightens ears, dolicocephalic.

Type 4) K´hala. Although this denominative is not in the Bertonio vocabulary it is used since the grandfathers, in the fields and in the city; so we considered it correct. The characteristics to this dog are: hairless, dolicocephalic, small and medium size, straighten ears.

Type 4) K´hala. Although this denominative is not in the Bertonio vocabulary it is used since the grandfathers, in the fields and in the city; so we considered it correct. The characteristics to this dog are: hairless, dolicocephalic, small and medium size, straighten ears.

The dog was one of the elements in the Andean weltanschauung, it participated in the form of seeing the world (duality, complement, between others) of the prehispanic societies; all this very attached to their religion. If the dog was an important part in the non-ceremonial activities and as companion, this function turn into a ritual when the owner died, because this use was more important when they died so we can find bony remains, representations, myths and beliefs about the dog and it's relation with people's deaths.

With the pass of time and new investigations for South America we will compare results and really see if changes about the dog's function in different religions and epochs existed, in this moment this is the relation of the dog with the Andean societies of the past for the North High plateau of Bolivia region.

Figure 2. Archaeological and archaeozoological analysis results material from Canis familiaris.

|

Material |

Site |

Filiation |

Chronology |

Context |

Use/Function |

Physical Characteristics |

|

Bony (skeleton) |

Chiripa (Quispe) |

Tiwanaku Postclassic and/or Pacajes |

800-1200 A.D. |

Agricultural |

Offering |

Male, big size, 61 cm high, head-body length 96,43 cm, weight 14.5 kg, dolicocephalic, possibly had straighten ears, age 5 years, hairy body. |

|

Bony (skull) |

Qiwaya |

Medium Chiripa |

1000-800 B.C. |

Ritual |

Offering |

Male, possibly medium size, dolicocephalic, possibly straightens ears, age 3 to 4 years, hairy body. |

|

Bony (skull) |

Qiwaya |

Medium Chiripa |

1000-800 B.C. |

Ritual |

Offering |

Female, possibly medium size, dolicocephalic, probably straightens ears, age 3 to 3 years, hairy body. |

|

Bony (skull part) |

Qiwaya |

Andean Confederations |

XIV century |

Funerary |

Companion/dowry part |

Sex could not be identified, small size, age 3 years, hairy body. |

|

Bony (one rib) |

S. Huata (Kollihumachipata) |

Medium Chiripa |

1000-900 B.C. |

S/I |

?Food? |

Small size. |

|

Bony (two rib fragments) |

S. Huata (Kollihumachipata) |

Late Chiripa |

800-200 B.C. |

Trash |

?Food? |

Small size. |

|

Bony (dental parts, teeth, talus) |

S. Huata (Lakaripata) |

Late Pana |

200-300 A.D. |

Use surface |

Food |

Male, small size, age 1 year, hairy body. |

|

Bony (skull) |

Tiwanaku |

Classic Tiwanaku |

500-900 A.D. |

Ceremonial |

Offering |

Male, medium size, dolicocephalic, age 7 to 8 years, hairy body. |

|

Bony (maxilla superior part) |

Tiraska |

Classic and expansive Tiwanaku |

400-1 100 A.D. |

Funerary |

Death world companion/dowry |

Small size, age five months, hairy body. |

|

Ceramic (Keru or ceremonial vase) |

Tiwanaku |

Classic Tiwanaku |

500-700 A.D. |

Ceremonial |

Hunt companion |

Possibly medium size, dolicocephalic, straightens ears, hairy body. |

|

Ceramic (Little figure) |

Jiquilla |

Wankarani |

1200 a. C 250 B.C. |

Funerary |

?Dowry part? Death world companion |

Mesaticphalic? straighten ears. |

|

Ceramic (Part of a plate holding part) |

S. Huata (El Calvario) |

Omasuyos / Inka |

1 500 A.D. |

Defensive |

Ritual |

Braquicephalic, fallen ears, possibly hairy body. |

|

Lithic (Stella iconography) |

Tiwanaku |

Medium Chiripa |

1000-800 B.C. |

Ceremonial |

Ritual |

Dolicocephalic and mesaticephalic, straighten ears, hairy body. |

|

Lithic (tablet iconography) |

Chiripa |

Chiripa |

1500-1 000 B.C. |

? |

Ritual |

Probably male and female, dolicocephalic with straighten ears and short legs, hairy. |

|

Metal (little statue) |

Tiwanaku |

Inka? |

? |

? |

Symbolic |

Males, dolicocephalic, with straighten ears, short legs. |

|

"Mummy dog" photograph |

Carangas |

Carangas? |

1200-1450 A.D. |

Funerary |

Death world companion |

Probably medium size and adult age, hairless or K´hala. |

Endnotes

a. Also known as Andean Confederations period

b. Three pieces (bone, wood and metal) belong to the andine fox Pseudalopex culpaeus

References

1. Mendoza, V. El perro en las sociedades andinas del pasado: un aporte arqueozoológico (Del Formativo al Inkario. Altiplano norte de Bolivia). Tesis de Licenciatura, Carrera de Arqueología. Universidad Mayor de San Andrés, La Paz, Bolivia, 2004.

2. Montes de Oca, I. Geografía y recursos naturales de Bolivia. 1997.

3. Posnanky, A. Tihuanacu. La cuna del hombre americano. Vol. IV, 1896.

4. Cordero, G. Descubrimiento de una estela lítica en Chiripa. En: Jornadas Peruano-bolivianas de Estudio Científico del Altiplano boliviano y del sur del Perú, Arqueología en Bolivia y Perú. Casa Municipal de la Cultura "Franz Tamaño". Tomo II, Universo, La Paz, 1997.

5. Ponce, C. Bolivian Precolumbian Cultures. Confirmado International. 1977.

6. Manzanilla, L. Akapana. Una pirámide en el centro del mundo. UNAM-IIA, México, 1992.

7. Lemuz, C. Patrones de Asentamiento Arqueológico en la Península de Santiago de Huata, Bolivia. Tesis de Licenciatura, carrera de Arqueología, UMSA, La Paz.

8. Paz, J. Excavaciones en Quispe. En: Excavaciones en Chiripa, Proyecto Arqueológico Taraco, Informe presentado a la DINAAR, Enero, La Paz, 2000.

9. Crockford, S. Osteometry of Makahan Coast Salish Dogs. Archaeology Press Simon Frayser University. Vancouver Canadá, 1997.

10. Valadez, R. and G. Mestre. Historia del Xoloitzcuintle en México. Instituto de Investigaciones Antropológicas de la UNAM, Museo Dolores Olmedo Patiño, Cámara de Diputados, México D.F., 1999.

11. Valadez R., A. Blanco, B. Rodríguez, F. Viniegra and K. Olmos. El perro maya Un nuevo tipo de perro prehispánico? AMMVEPE 1999; 10(5):131-138.

12. Valadez R., B. Paredes and B. Rodríguez. Entierros de perros descubiertos en la antigua ciudad de Tula, Latin American Antiquity. 1999; 10(2):180-200.

13. Valadez, R., A. Blanco, F. Viniegra, K. Olmos and B. Rodríguez. El Tlalchichi, perro de patas cortas del occidente mesoamericano. AMMPEVE 2000; 2: 49-57.

14. Fernández. M. Teoría y Método de la Arqueología. Editorial Síntesis, 2da edición, Madrid, 2000.

15. Platt, T. Espejos y Maíz. Temas de la estructura simbólica, Cuadernos de Investigación CIPCA, No. 10, La Paz, 1976

16. Guaman Poma de Ayala, F. El Primer Nueva Corónica y Buen Gobierno. Editores John V. Murra y Rolena Adorno (Traducción Jorge L. Urioste), Tomo I, II, II. 2da edición, Editorial Siglo XXI, México, 1988[1615].

17. Mendoza, V. and R. Valadez. Los perros de Guaman Poma de Ayala: visión actual del estudio del perro precolombino sudamericano. AMMVEPE 2003; (2):43-52.

18. Cobo, B. Obras del Padre Bernabé Cobo. Historia del Nuevo Mundo. Biblioteca de Autores Españoles, Tomo Nonagesimoprimero, Estudio preliminar y edición al P. Francisco Mateos de la Compañía de Jesús, Madrid, 1964.

19. Radio San Gabriel. Transcripción del Vocabulario de la lengua Aymará. P. Ludovico Bertonio. Biblioteca del Pueblo Aymará. La Paz, 1993[1612].