Ian K. Ramsey, BVSc, PhD, DSAM, FHEA, DECVIM-CA, MRCVS

Polyuria (PU) and polydipsia (PD) are common presenting signs in dogs but less common in cats. There are several causes and these can be divided into two groups: primary PU/secondary PD and primary PD/secondary PU. Some causes may produce clinical signs by more than one mechanism. Compensatory mechanisms that regulate water homeostasis mean that PU and PD always occur together.

Causes of PU and PD

Causes are listed in Figures 1 and 2.

In cats chronic renal failure and diabetes mellitus are by far the commonest causes of PU/PD as a presenting sign. In dogs the list is longer; diabetes mellitus, chronic renal failure, hyperadrenocorticism (HAC), endotoxaemia and hypercalcaemia may all present with PU/PD in the absence of other signs.

The Importance of a Logical Approach

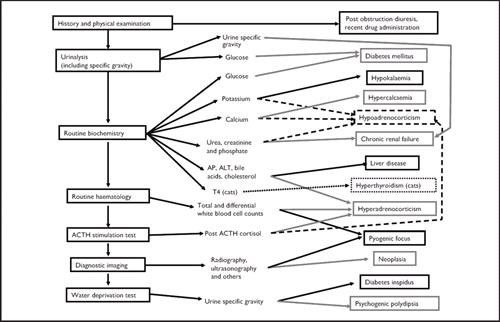

As PU/PD is such a common presenting sign, it is often tempting to 'spot diagnose' the cause or to treat the sign non-specifically or on a trial basis as a means of diagnosis. While these approaches may be acceptable for some other presenting signs (e.g., acute diarrhoea), they are rarely justifiable on medical or economic grounds in cases of PU/PD. This is because some causes of PU/PD require prompt or even emergency management; others carry a poor prognosis and few will respond to empirical therapy with antibacterial agents or glucocorticoids. A logical approach to PU/PD should be in the following general order (for summary see Figure 3).

History

PU/PD is rarely observed in a consultation and identification of this problem requires owner observation. In some cases, it is useful to hospitalise dogs and cats to accurately measure their water intake. However, it is important not to dismiss an owner's report of PU/PD when the quantities of water being consumed or urine being produced seem normal. Changes in thirst are as important an indicator of disease as an increase above a specific limit. Although a full history should always be obtained, it is particularly important to define the nature and progression of the PU/PD: any loss of toilet training; any changes in urine colour or odour; recent drug administration and any signs of other diseases (e.g., changes in body weight or skin condition, ocular, vulval or preputial discharges, diarrhoea, vomiting or changes in appetite).

Many dogs that present with PU/PD will also have nocturia (a voluntary desire to urinate at night). This must be distinguished from incontinence by the lack of soiled bedding and/or hair coat. However, animals with severe PU/PD may develop true urinary incontinence. PU/PD should therefore be properly excluded before investigating or treating cases that present with urinary incontinence.

Figure 1. Causes of primary PU/secondary PD.

|

Diabetes mellitus |

Neoplasia |

Hyperthyroidism |

|

Chronic renal failure |

Hypoadrenocorticism |

Fanconi's syndrome |

|

Liver disease |

Hypokalaemia |

Primary renal glucosuria |

|

Hyperadrenocorticism (HAC) |

Endotoxaemia (e.g., pyometra) |

Phaeochromocytoma |

|

Hypercalcaemia |

Central diabetes insipidus |

Post-urethral obstruction diuresis |

|

Drugs (e.g., steroids, diuretics) |

Nephrogenic diabetes insipidus |

Polyuric acute renal failure |

Figure 2. Causes of primary PD/secondary PU.

|

Pain, stress, heat, exercise |

Hyperthermia |

Psychogenic PD |

Clinical Examination

Particular attention during the clinical examination should be paid to the:

Peripheral lymph nodes (for evidence of neoplastic and, in other countries, granulomatous diseases)

Peripheral lymph nodes (for evidence of neoplastic and, in other countries, granulomatous diseases)

Skin (for dermatological changes associated with HAC)

Skin (for dermatological changes associated with HAC)

Vulva (for evidence of pyometra)

Vulva (for evidence of pyometra)

Abdomen (for evidence of organomegaly, small kidneys, bladder size etc.)

Abdomen (for evidence of organomegaly, small kidneys, bladder size etc.)

Rectum (especially in female dogs due to the possibility of anal sac adenocarcinomas)

Rectum (especially in female dogs due to the possibility of anal sac adenocarcinomas)

In cats the cervical region should be carefully palpated for the presence of goitres.

Urinalysis

Dipstick urinalysis should be performed immediately to check for the presence of glucose and ketones. The presence of glucose in the urine is highly suggestive, but not diagnostic, of diabetes mellitus. Glucosuria in the absence of hyperglycaemia is associated with certain renal tubular disorders such as Fanconi's syndrome. Ketonuria is almost invariably associated with glucosuria in the dog and is a reliable indicator of ketosis. Proteinuria, haematuria and haemoglobinuria do not cause PU but some conditions that cause proteinuria etc. may lead to PU by other mechanisms.

Specific gravity (s.g.) should also be determined. In most cases the urine will be isosthenuric (1.008-1.015) or minimally concentrated (<1.025). In a very few cases of diabetes mellitus with severe glucosuria the s.g. will be >1.035. All causes of PU/PD that result in anti-diuretic hormone (ADH) resistance, not just primary diabetes insipidus, can lower the urine specific gravity to hyposthenuric values (<1.008). In particular, a significant proportion of dogs with hyperadrenocorticism have hyposthenuric urine.

Sediment examination is of less benefit in the investigation of PU/PD but should still be performed to look for renal casts associated with pyelonephritis. Urinary crystals, bacteria and inflammatory cells may be seen and the technique is useful to distinguish haemoglobinuria from haematuria.

Serum Biochemistry

The most important parameters to measure are the glucose and calcium concentrations because hypercalcaemia and hyperglycaemia need to be identified at an early stage to prevent patient deterioration. Hypercalcaemia is seen in a number of neoplastic conditions (particularly lymphoma), hypoadrenocorticism, hyperparathyroidism and some forms of chronic renal failure (particularly those associated with juvenile nephropathies). Severe hyperglycaemia (>12 mmol/l) is seen in diabetes mellitus. In the cat even severe hyperglycaemia may be stress induced and therefore fructosamine measurement is indicated.

Other changes that are of use include those suggestive of renal azotaemia (increases in urea, creatinine and phosphate with normal electrolytes and a urine specific gravity of<1.025); hypoadrenocorticism (increases in urea, creatinine, phosphate and potassium with a low sodium); HAC (increases in liver enzymes, particularly alkaline phosphatase (AP), and cholesterol); and liver disease (decreased urea, albumin and increased liver enzymes). In cats a measurement of total thyroxine is indicated at this stage to exclude hyperthyroidism.

Haematology

Haematology is of less use than urinalysis and serum biochemistry in the investigation of PU/PD. Changes in the white blood cell counts are common but are frequently non-specific (with the exception of leukaemia). Anaemia does not cause PU/PD but can be associated with renal disease which does.

Hyperadrenocorticism (HAC) Screening Tests

HAC is one of the commonest causes of PU/PD in the absence of changes on routine biochemistry etc. that suggest other diagnoses. PU/PD may also be seen in the absence of other clinical changes (such as alopecia) that are normally associated with HAC. For these reasons a screening test for HAC is indicated early in the investigation of PU/PD. The author prefers the ACTH stimulation test for this purpose. However, in those countries where ACTH is very expensive the low-dose dexamethasone suppression test (LDDST) may be preferred. The advantage of using the LDDST is the increased sensitivity. The disadvantages are the length of time the test takes to perform and the higher number of false-positive results. The method and interpretation of both of these tests are described in the BSAVA Manual of Canine and Feline Endocrinology.

Radiography

Survey radiographs of the thorax and abdomen are useful to identify neoplastic masses, changes in kidney, liver size, large pyogenic foci (pyometra, prostatic abscesses, etc.) and enlargement of some non-palpable lymph nodes. The larger the dog the more important it is to do abdominal radiography as the sensitivity of abdominal palpation in detecting abnormalities falls considerably in dogs with larger girths.

Ultrasonography

Ultrasonographic examination of abdominal viscera is only useful in the investigation of PU/PD for which no cause has been suggested by those clinical tests mentioned above. Survey ultrasonography, especially in older animals, often identifies nonsignificant abnormalities, such as splenic hyperplasia and hepatic nodular change, and care must be taken not to over-interpret such findings. Ultrasonography (often coupled with guided fine-needle biopsy) is, however, invaluable for the further assessment of suspected hyperadrenocorticism, liver disease, pyogenic foci and abdominal masses.

Modified Water Deprivation Test

The water deprivation test is probably over-used in some veterinary practices. Even if done properly it is a time-consuming and expensive test that poses a small risk to the patient. If done badly it may pose a significant risk to the patient and is a waste of time and money. The test should only be performed once renal disease, diabetes mellitus, hypercalcaemia, hyperadrenocorticism and liver disease have been excluded. The test is therefore principally of use in distinguishing between psychogenic PD and central and nephrogenic forms of primary diabetes insipidus (i.e., primary deficiencies of ADH or its receptors). The method and interpretation of this test are described in the BSAVA Manual of Canine and Feline Endocrinology.

Further Investigations

If a water deprivation test has demonstrated primary central diabetes insipidus then the logical step is to perform some form of advanced diagnostic imaging of the brain and pituitary. In most instances, this will require referral. If primary nephrogenic diabetes insipidus is diagnosed then renal ultrasonography is indicated. Renal biopsies are unlikely to alter the therapeutic options of such cases and are usually unnecessary. If psychogenic polydipsia is suspected then behavioural modification is required and water may be restricted though not withdrawn. This 'final' diagnosis is largely one of exclusion and is rare. The cases seen by the author tend to be big young dogs who drink too much as part of a generally over-boisterous nature. Rarely, psychogenic polydipsia may occur as a result of attention-seeking behaviour.

Summary

See Figure 3.

Click on the image to see a larger view.

| Figure 3 |

Summary of approach to PU/PD.

ACTH = adrenocorticotropic hormone; ALT = alanine aminotransferase; AP = alkaline phosphatase. |

|

| |

References

1. Mooney CT, Peterson ME. eds. BSAVA Manual of canine and feline endocrinology (third edition). BSAVA Publications, Gloucester, 2004.

2. Ramsey IK, McGrotty YL. Polyuria and polydipsia in dogs. In Practice 2002; 24: 434-441.