Abstract

Intravenous therapy is a cornerstone of veterinary medicine and has become essential for a variety of treatments. Historically, IV catheters have not been routinely utilized in marine mammal medicine.1,2 The unique anatomy of marine mammals, combined with the constraints imposed by their aquatic environment, have made placement and maintenance of IV catheters difficult. This paper discusses several techniques for placement and long-term management of intravenous catheters in marine mammals.

Over a 6-yr period, intravenous catheters have been utilized on nine occasions in both pinnipeds and cetaceans (two harbor seals [Phoca vitulina], four walrus [Odobenus rosmarus], two beluga whales [Delphinapterus leucas], one pygmy sperm whale [Kogia breviceps]), for durations up to 9 days in length. The use of a Tuohy needle (Reganes Medical & Surgical Supplies, Clearwater, FL 33519 USA) in conjunction with an epidural catheter (SIMS Medical Systems, Keene, New York, 03431 USA) allows catheterization of vessels which are too deep to visualize or palpate. The Tuohy needle is a 17-ga 8.9-cm metal needle, which acutely curves at its most distal point (Figure 1). The Tuohy needle can be inserted perpendicular to the skin and its curved tip displaces the 20-ga nylon epidural catheter at an angle as it leaves the needle and enters the blood vessel. Although the IV epidural catheter technique provides rapid, reliable venous access, the 20-ga catheter is prohibitively small for adequate fluid therapy of large animals. In order to provide adequate fluid therapy, larger catheters can be placed. Traditional through-the-needle catheters can be used with marine mammals, but are more difficult to place. The needle must be introduced at an oblique angle such that when the catheter is inserted through the needle and into the vein, it will not be forced to make an abrupt turn. In seals and walrus, a 10-ga 13.3-cm large-animal veterinary catheter (Jorgensen Laboratories, Inc., Loveland, CO 80538 USA) is used to penetrate the vein. The metal portion is removed and then a 14-ga 61-cm catheter (Charter Med, Lakewood, NJ 08701 USA) can be introduced through the catheter sleeve. The 10-ga catheter sleeve is withdrawn and cut away, leaving the longer 14-ga catheter in place for long-term use. We have commonly used these larger catheters for intraoperative fluid therapy and postoperative IV medications for up to 9 days.

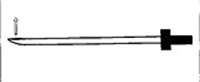

Figure 1. Diagram of a Tuohy needle created for human epidural catheterization

These needles have a closed terminal end and side hole (arrow), which allows the catheter to exit at an angle.

In seals and walrus, the dorsal extradural intravertebral vein is used for catheter placement. This large venous sinus is approached in the caudal lumbar region (L3-L4) on the dorsal midline (Figure 2). Although this location is a common venipuncture site,1,2 catheterization is difficult due to the depth of this sinus and the oblique needle angle necessary for access. The use of a Tuohy needle and epidural catheter allow these obstacles to be easily overcome. These catheters are routinely used at the Wildlife Health Center for initial IV access during pinniped chemical restraint. Venous catheterization is commonly accomplished after intramuscular sedation and this IV line is then used for anesthetic induction. The catheter can be secured in place and used intra- and postoperatively for administration of IV medications.

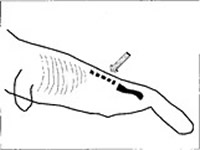

Figure 2. Schematic diagram of a seal or walrus illustrating the extradural intervertebral vein catheterization site (arrow) at the 3rd–4th lumbar vertebrae

In cetaceans, the large caudal ventral peduncle veins run on either side of ventral midline just below the laterally bulging vertebral tendon sheaths (Figures 3 and 4).2 These vessels lie deep within the peduncle and can be difficult to locate and catheterize. Long-term catheterization of the vessels within the fluke has had limited success. While these vessels are commonly used for venipuncture, they are not as amenable for catheterization, both because of their relatively small size and because the arteries are surrounded by the periarticular venous retia.3,4 This vascular plexus has thick muscular walls, which can constrict and prevent catheter placement. Due to the close association between the fluke arteries and veins, it is very difficult to specifically catheterize one versus the other. Catheterization of the ventral peduncle veins is best performed using a Tuohy needle and epidural catheter. The depth of the vessel and the oblique needle angle required for through-the-needle catheters make this type of catheter difficult to use in cetaceans.

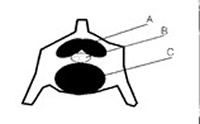

Figure 3. Schematic diagram of the extradural intravertebral vein (A), cauda equina (B), and intervertebral disc (C) within a lumbar vertebral of a seal or walrus

Figure 4. Schematic diagram of the caudal peduncle in a cetacean showing the relationship of the vertebral body (A), tendon sheath (B), and ventral peduncle vein (C)

Because marine mammal catheters are not placed on an appendage, but rather on the animal’s large trunk, bandaging is impractical and securing the catheter can be difficult. It has been challenging to adequately maintain these catheters in an aquatic environment while attempting to maintain a degree of cleanliness and sterility. Due to hydrodynamic forces, catheters in cetaceans must be very tightly secured at their base and there must be a minimal length of catheter extending from the body. In some situations, a rubber flap has been sutured over the catheter to protect it from the drag of water while swimming. The use of a silicone-filled rubber syringe plunger has allowed firm attachment of the catheter to the skin and created a semi-sterile barrier where the catheter exits the skin. The rubber plunger from a 20-cc syringe is removed and filled with silicone. After the catheter has been placed, a small rim of triple antibiotic ointment is applied to the catheter/skin junction. The syringe plunger is then used to cap the site by driving a needle through the silicone-filled plunger and placing the catheter through the needle. The needle is then withdrawn and the catheter remains, snugly passing through the plunger. The plunger is advanced down to the skin surface where it is sutured in place. The catheter and injection cap are joined together with a rapid-setting epoxy glue and sutured to the skin. A thin layer of oil-based triple antibiotic ointment is placed over the external catheter and injection cap. Pinnipeds with IV catheters are removed from their pool and kept in a holding area with water sprinklers. Cetaceans with IV catheters are kept in water and briefly restrained for IV medication administration.

Like their terrestrial counterparts, marine mammals may require intravenous fluids or medications for a variety of reasons. Although marine mammals lack the conventional arms, legs and neck, which are commonly used for catheter placement, intravenous catheters can be placed and maintained for relatively long periods in pinnipeds and cetaceans. Access to the large vessels of marine mammals requires unusually long needles and catheters. These catheters are not bandaged in place but secured with the use of rubber/silicone plungers which are sutured in place. These catheters have been used for fluid therapy, anesthetic induction, antibiotic administration, plasma transfusion, blood sampling and parenteral nutrition.

Acknowledgments

The authors are indebted to Drs. Raphael, Klein, Mangold and James for their clinical assistance and Kevin Walsh, Hans Walters, Chris Baker, and the marine mammal trainers and keepers for their help. We would also like to thank Dolores Sanginito for her tremendous help with manuscript preparation.

Literature Cited

1. Dierauf, L.A. (ed.). 1990. Handbook of Marine Mammal Medicine: Health, Disease, and Rehabilitation. CRC Press.

2. Fowler, M.E. (ed.). 1986. Zoo and Wild Animal Medicine. 2nd ed. W.B. Saunders Co., Philadelphia, Pennsylvania. PA.

3. Harrison, R.J. (ed.). 1974 Functional Anatomy of Marine Mammals. Vol. 2 Academic Press, London, New York, San Francisco.

4. Ridgway, S.H., R. J. Harrison. (ed.). 1981. Handbook of Marine Mammals. Vol. 1 Academic Press, London, New York, San Francisco.