Deleterious Effects of Onychectomy (Declawing) in Exotic Felids and a Reparative Surgical Technique: A Preliminary Report

Abstract

Onychectomy, or declawing, is a controversial and morbid procedure when used in the management of exotic felids. There are three basic techniques, all of which lead to significant gait disturbances and boney deformities. Although each method of onychectomy has a purported rationale, every declawed animal we have encountered manifests some degree of dysfunction, such as abnormal standing conformation and the slow and painful placement of paws during ambulation. Fourteen declawed exotic felids with morbid sequelae of onychectomy have been treated with a reparative surgical technique. Over 90 percent of these animals have exhibited markedly improved gait and stance.

Introduction

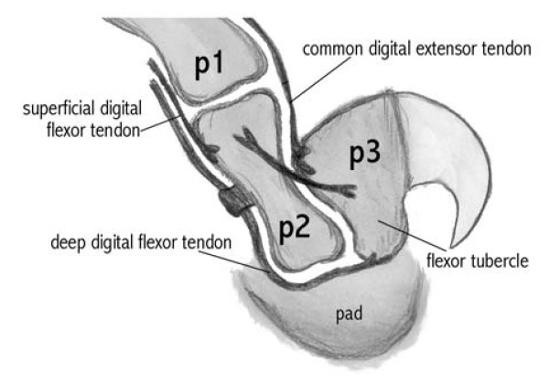

Onychectomy is a popular technique used in the management of exotic felids. Three basic methods have been described. In the first (method one), the entire third phalanx of each digit is removed.2 In the second (method two), most of the third phalanx is amputated, leaving the deep digital flexor tendon attached to the remaining flexor tubercle.3 The third (method three) is described as leaving the flexor and extensor tendons attached to the third phalanx, while removing the horn-forming tissue on the ungual crest.1,2 Each of the methods has reported advantages, but none is free of adverse sequelae.

While proponents of method one accurately claim that complete removal of the third phalanx (p3) minimizes potential of subsequent infection and trauma caused by the retained bone fragment,2 the disruption of flexor and extensor tendons, as well as the abnormal position of the second phalanx (p2), cause digital pad pathology and loss of function, namely flexion and extension of the paw.

Method two supporters argue that the deep digital flexor tendon should be preserved.3 While this allows for some flexion of the paw, without the counter action of the extensor tendon, the flexor pulls the fragment of p3 proximally under p2. This causes digital pad pathology as well as discomfort for the animal as it attempts to walk on the remaining bone,2 which acts like a “pebble in the shoe.”

Advocates of method three correctly state that paw integrity will be maintained with flexor and extensor tendon preservation, Because of the nature of the feline claw,1 however, it is impossible to remove all of the horn-secreting tissue without removing the majority of p3.2 Subsequent nail regrowth and abscess formation can be expected.

The Wildlife Waystation is home to more than 130 big cats. Onychectomy is not performed at our facility, but many animals have been declawed prior to their arrival. Every one of these cats has suffered to some degree from the crippling effects of declaw surgery. These effects have been ameliorated by the new reconstructive surgery described in this paper. To date, we have repaired thirty-four paws with significant improvement in function and apparent reduction in pain.

Anatomic Review

Normal anatomy of the claw is provided in Figs. 1 and 2.

| Figure 1 |

Normal anatomy, claw. |

|

| |

| Figure 2 |

Normal anatomy, claw. |

|

| |

Methods

Eight cougars, three tigers, two leopards, and one lion have had either their front feet, or both their front and back feet repaired. Pre-operative measurements of pad size and subjective ratings of paw pad suppleness and integrity were made. Radiographs, and in some cases, magnetic resonance images, were used to assess the status of p2 and p3 and the presence of pathology, including soft tissue infection, osteomyelitis, bone degeneration, and arthritis. In the front paws of two cougars, p3 had been completely amputated in the initial declaw surgery. In the front paws of the remaining six cougars, p3 had been only partially amputated. In two animals there was significant nail regrowth with subsequent abscess formation. All three tigers had only partial amputations of p3, with one animal having significant nail regrowth and abscess formation. Both leopards had only partial amputations of p3, one with abscess formation. The lion had partial amputation of p3 with subsequent abscess formation due to nail regrowth.

Digital video recordings have been taken of the animals walking before and after the surgery. The video is used to monitor changes in the animals’ ability to walk, jump, and climb.

In preparation for surgical repair of the declawed feet, paws are clipped to the carpus, including the area of the former nail. Chlorhexidine solution is then sprayed on the paw before the Esmarch bandage tourniquet is wrapped from the distal paw towards the antebrachium in a binding manner to milk blood from the paw. Care must be taken to apply pressure over a broad area to avoid nerve damage. The tourniquet is then released from the distal end toward the proximal to expose the paw. After a complete surgical scrub, an incision approximately 3 cm in length is made from the dorsal aspect of the paw to the palmar aspect at the site of the former nail. The pad must be avoided. In the case where part of p3 remains, the partially amputated bone is exposed via blunt dissection, any purulent material is debrided and the fragment is then grabbed with A-O reduction forceps to mobilize and exteriorize the deep digital flexor tendon. A cruciate suture (0 PDS) is placed in the remaining digital flexor tendon and attached dorsally into the extensor tendon, or if the latter cannot be identified, into the remaining tissue in the extensor groove of the second phalanx. Before the suture is secured, the cartilage that remains on the distal end of p2 is removed by rongeur. The suture is then tightened to reposition the pad nearer to its proper anatomic position relative to p2. The incision is closed with tissue glue. Pressure wrap bandages are placed over the paws with tabs for easy release.

In the case where p3 has been completely amputated, the surgical technique is similar to the one described above, except that the tendons may be difficult to find. The cartilage of p2 is removed by rongeur and the pad repositioned, as described above.

Anesthesia consists of the following. Medetomidine (0.05 mg/kg) is administered intramuscularly via hand syringe or blow dart. The drug typically induces vomiting before the animal is adequately sedated. A mask delivering isofluorane and oxygen is then placed over the nose and mouth until the animal can be transported. After intubation, an intravenous catheter is placed. The level of anesthesia is monitored with respect to pain response, heart rate, and respiration. Intravenous cefazolin (20 mg/kg q 90 minutes) is given during the course of the procedure. Butorphanol (0.2–0.4 mg/kg) is administered subcutaneously at the completion of the surgery for pain control. The reversal agent atipamezole (0.25 mg/kg) is given intravenously. The animal is recovered on a smooth plywood floor.

Because tigers are more sensitive to anesthesia, we find it easier to use xylazine (0.75 mg/kg) intramuscularly followed by ketamine (1.5 mg/kg) intramuscularly in these animals. For this anesthesia, we use the reversal agent yohimbine (0.125 mg/kg) intravenously. Postoperative pain management includes butorphanol (0.1 mg/kg) subcutaneously.

Results

In this study, the preliminary data depict that all fourteen declawed animals have shown improvement in their gait. Travel times over specific distances are improved as well as ability to jump and climb. With the reparative surgery described in this paper, animals have regained significant function of their feet. Whereas before surgical repair, their paws were paddle-like, a condition commonly referred to as “floppy paw,” they are now able to stand digitigrade1 and have improved ability to flex and extend their front paws. Subjective ratings of paw pad suppleness and integrity improved for all animals.

These surgeries were performed between April 2000 and March 2002. There have been no surgical complications in the fourteen animals treated to date.

Fourteen paws exhibited nail regrowth with abscess formation prior to reparative surgery. All were treated successfully, and there have been no recurrences.

Subjective analysis of the videotapes shows marked improvements in ambulation in 13 of the 14 animals treated by this reparative technique.

Discussion

There are three well-described methods of declawing exotic felids. Each has its purported arguments, but none is without morbid sequelae.

In the case where p3 is only partially amputated, the flexor tendon attachment pulls the fragment of p3 ventrally and proximally.2 The animal is forced to either walk on the toes despite the painful “pebble in the shoe” phenomenon or, avoid walking digitigrade and bear its weight on the carpus. These paws are easier to repair those where p3 is entirely amputated because the tendons can be identified and because the pad is not drawn as far proximally.

Where p3 is entirely removed, the flexor and the extensor tendons are difficult to find due to retraction. In these cases, the tendon reattachment reparative technique described above can only be approximated. However, approximated tendon reattachment, with the proper repositioning of the digital pad and the removal of the cartilage and shortening of p2, improved the gait of these animals.

Despite claims to the contrary, our experience shows that none of the three described methods of declawing is able to preserve the normal anatomy and function of the paw. When p3 is completely amputated, the animal may not have subsequent infection, but the paws lose much of their anatomic integrity and become paddle-like, flat, and unable to flex and extend. Anatomic changes of the distal part of the paw cause p2 to stab through the pad, causing pad pathology.

Where p3 is partially amputated, animals exhibit one or both of the following outcomes. The first is abscess formation due to incomplete removal of the nail germinal tissue, and the second is that the residual portion of p3 is pulled under p2 causing pathologic disruption of the pad and arthritis in the entire limb due to abnormal stance.

We have found that the removal of the distal cartilage of p2 allows pressure-induced resorption and subsequent remodeling of the bone. This ultimately has a positive effect on the digital pad because p2 no longer penetrates it.

The attachment of the deep digital flexor tendon to the extensor tendon allows the cat to regain some degree of flexion and extension of the paw.

This reparative surgical technique is not to be construed as another method of declawing. The animals have not been restored to normal function. Their symptoms have only been palliated.

Acknowledgments

This work was completed due to the generous support of M. Colette, P. Summers, B. Countryman, J. Stridde, L. LeClerc, A. Flores, J. Hinchliffe, S. Steele, J. Caruso, J. Jensvold, M. Sebastian, A. Bennett, the volunteers and staff of the Wildlife Waystation, and the staff at Animal Specialty Group.

Literature Cited

1. Fowler M. Hoof, claw and nail problems in nondomestic animals. J Am Vet Med Assoc. 1980;177:885–893.

2. Fowler M, McDonald S. Untoward effects of onychectomy in wild felids and ursids. J Am Vet Med Assoc. 1982;181:1242–1245.

3. Peddie J. Onychectomy in the exotic feline. In: Bojrab MJ, ed. Current Techniques in Small Animal Surgery. Philadelphia, PA: Lea & Febiger; 1983:517–519.