Treatment of Anestrus Due to Hyperprolactinemia with Cabergoline in a Captive Asian Elephant (Elephas maximus)

Abstract/Introduction

Hyperprolactinemia (serum prolactin concentrations ≥15 ng/ml) has been identified in 13 of 31 African (Loxodonta africana) and one of six Asian elephants (Elephas maximus) by the Conservation and Research Center (CRC) Endocrine Research Laboratory, Smithsonian Institution, National Zoological Park, Front Royal, VA. Most of these elephants are flat-liners with low serum progesterone (<0.1 ng/ml) but some are cycling normally. Treatment regimens for anestrus due to hyperprolactinemia has been reported in humans and several other species with a dopamine agonist such as bromocriptine or more recently cabergoline.3,9 The most common cause of hyperprolactinemia is a slow-growing, benign, prolactin-secreting pituitary adenoma,5,10 although other pathologies can elevate serum prolactin concentrations. An anestrus Asian elephant with hyperprolactinemia was successfully treated and began normal cycling after 6 months of cabergoline therapy.

Case Report

A 28-year-old Asian elephant at Busch Gardens Tampa Bay (BGT) was diagnosed with hyperprolactinemia by CRC in October 1997. At this laboratory, serum prolactin concentrations in hyperprolactinemic females averaged 34.0±18.8 ng/ml (range 15.4–71.1 ng/ml) as compared to concentrations for non-cycling flatliner elephants with ‘normal’ prolactin levels (6.7±4.1 ng/ml; range 1.8–11.9 ng/ml). The BGT elephant was unusual in that elevated serum progesterone concentrations (0.5–1.0 ng/ml) were present in contrast to the traditional flat-liners identified by CRC. Repeated rectal ultrasound exams confirmed that neither pregnancy nor mummified fetus was present.

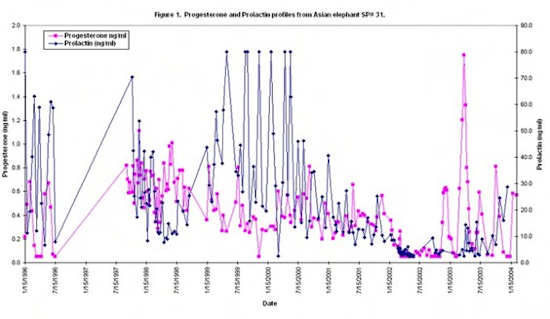

In May 2000, the elephant was diagnosed with Mycobacterium tuberculosis from a vaginal discharge. A standard course of treatment was instituted per the USDA Elephant Tuberculosis Guidelines and concluded in January 2002. Serum prolactin concentrations had started to decline, but were still elevated, and serum progesterone remained elevated; the elephant was not cycling. In March 2002, a course of cabergoline (Dostinex®, Pfizer Inc., Eastern Point Road, Groton, CT 06430, USA), 1 mg orally twice weekly for 6 months, was instituted following human guidelines.9 Serum prolactin concentrations declined almost immediately after the first treatment and were followed about 1 month later by return to baseline of progestins. Progestin secretion remained low until November 2002 when normal cycling resumed with observation of a normal luteal phase. From November 2002 through January 2004, the elephant has exhibited four normal estrous cycles. Prolactin concentrations have remained within the normal range for elephants, over 1 year after treatment withdrawal. In March 2003, she again had a vaginal discharge that was culture positive for Mycobacterium tuberculosis. This culture was a multi-drug resistant strain that had an identical molecular fingerprint to the original strain in May 2000. A revised treatment protocol was instituted and continues as of this writing. From November 2003 through mid-February 2004, prolactin concentrations were tending to rise to pre-cabergoline therapy concentrations (Fig. 1).

Figure 1

Cabergoline has been used to treat anestrus in humans8 and dogs3 and to control prolactin secretion in various mammals4. Cabergoline is a long-acting dopamine receptor agonist with a high affinity for D2 receptors. It exerts a direct inhibitory effect on the secretion of prolactin. Anti-tuberculocidial drugs, especially rifampin, are known to increase serum prolactin in humans (D. Ashkin, pers. comm.), but this is not consistent with the timing of the treatment in this case. Transient increases in prolactin can be caused by sleep, anorexia, protein ingestion, hypoglycemia, stress, and chest wall stimulation or trauma.4,10 The cause of the hyperprolactinemia in this elephant is suspected to be due to a pituitary tumor. Relapse of hyperprolactinemia is more common in humans with micro- or macroprolactinomas.2 Other evidence for a pituitary tumor in this elephant includes the elevated progesterone concentrations observed. This is documented in humans with prolactinomas.7 Prolactin is recognized as a cytokine and, with persistent immune activation, it may become elevated.6 One other African elephant with hyperprolactinemia was diagnosed with Mycobacteriosis bovis postmortem. Further examination of a possible association between tuberculosis in elephants and hyperprolactinemia is certainly warranted.

Literature Cited

1. Biller, B.M., M.E. Molitch, M.L. Vance, K.V. Cannistraro, and K.R. Davis. 1996. Treatment of prolactin-secreting macroadenomas with the once-weekly dopamine agonist cabergoline. J. Clin. Endocrinol. Metab. 81: 2338–2343.

2. Colao, A., A. Di Sarno, P. Cappabianca, C. Di Somma, R. Pivonello, and G. Lombardi. 2003. Withdrawal of long-term cabergoline therapy for tumoral and non-tumoral hyperprolactinemia. New Engl. J. Med. 349: 2023–2033.

3. Gobello, C., G. Castex, and Y. Corrada. 2002. Use of cabergoline to treat primary and secondary anestrus in dogs. J. Am. Vet. Med. Assoc. 220: 1653–1654.

4. Jochle, W., K. Arbeiter, K. Post, R. Ballabio, and A.S. D’Ver. 1989. Effects on pseudopregnancy, pregnancy and interoestrous intervals of pharmacological suppression. J. Reprod. Fertil. 39: 199–207.

5. Jones, E.E. 1989. Hyperprolactinemia and female infertility. J. Reprod. Med. 34: 117–126.

6. Montero, A.M., O.A. Bottasso, M.R.Luraghi, A.G. Giovannoni, and L. Sen. 2001. Association between high serum prolactin and concomitant infections in HIV-infected patients. Human Immunol. 62: 191–196.

7. Nass, T.E., H.L. Lapolt, and J.K.H. Lu. 1983. Gonadotropin secretion during prolonged hyperprolactinemia: basal secretion and the stimulatory feedback effect of estrogen. Biol. Reprod. 28: 1140–1147.

8. Verhelst, J., R. Abs, D. Maiter, A. Van den Bruel, M. Vandewdghe, B. Velkeniers, J. Mockel, G. Lamberigts, P. Petrossian, P. Coremans, C. Mahler, A. Stevenaert, J. Verlooy, C. Raftopoulos, and A. Bckers. 1999. Cabergoline in the treatment of hyperprolactinemia: a study of 455 patients. J. Clin. Endocrinol. Metab. 84: 2518–2522.

9. Webster, J., G. Piscitelli, A. Polli, C.Ferrari, I. Ismail, and M. Scanlon. 1994. A comparison of cabergoline and bromocriptine in the treatment of hyperprolactinemic amenorrhea. New Engl. J. Med. 331: 904–909.

10. Woolf, P.D. 1986. Differential diagnosis of hyperprolactinemia: physiological and pharmacological factors. In: Olefsky, J.M., and R.J. Robbins (eds.) Prolactinomas: Contemporary Issues in Endocrinology and Metabolism, vol 2. Churchill Livingstone, New York, New York. Pp. 43–65.