Use of the Combination Emodepside/Praziquantel in Reptiles: A New Drug for Endoparasite Management?

Abstract

Many anthelmintic compounds have been used in herpetological medicine. However, treatment of nematodiasis in reptiles can be very challenging, especially in stressed, noncooperative or dangerous species. Recently, a combination of emodepside and praziquantel (Profender®, Bayer Health Care group, Leverkusen, Germany) for topical application may be a promising alternative treatment option for the veterinarian. This presentation summarizes all the current information on the various nematocides known to be efficient in reptiles and describes the mode of action of Profender® in the cat as well as its potential use in reptiles.

Introduction

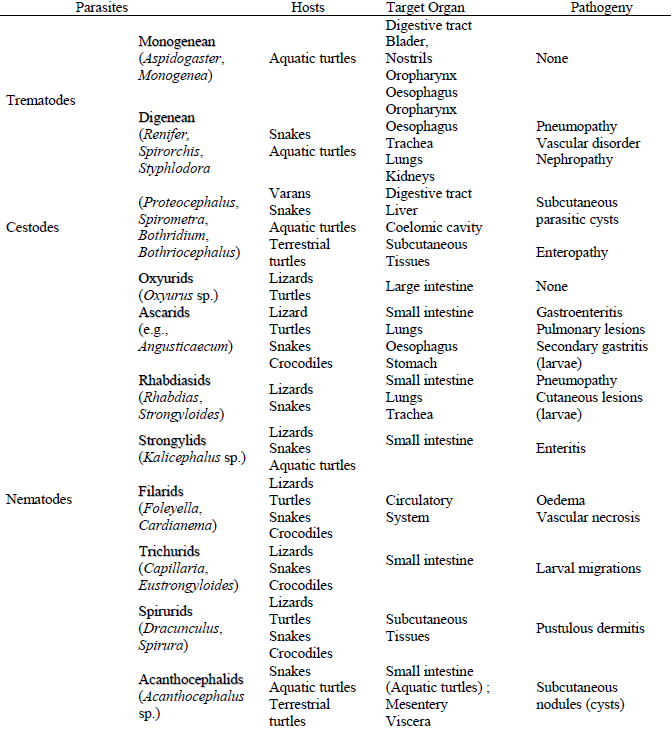

Intestinal helminths, pentastomids, intestinal and blood protozoans are common parasites of captive or wild reptiles (reptiles may serve as definitive, intermediate, accidental or paratenic hosts).1,3,4,6-8 Generally, these parasites are nonpathogenic or commensal in wild animals. However, they may become pathogenic when present in high concentrations or if the host is weakened by inadequate environmental conditions in captivity (Table 1).

Table 1. Helminths affecting reptiles3,4

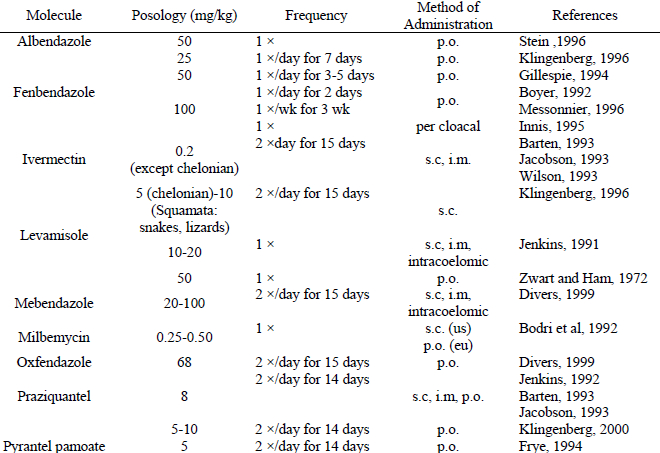

Most deworming protocols for reptiles (suffering from nematodiasis, cestodiasis, trematodiasis, and acanthocephaliasis) originated from domestic animal medicine experiences. Over time, some of these compounds were tested and became empirically recommended because of their efficacy and safety (Table 2).1-3,5-9,12 Many references promoting the use of these anthelmintic compounds in reptiles are currently available.1,6-9

Table 2. Anthelmintic compounds for control of intestinal parasites of reptiles1-3,5,8,12

Emodepside and Praziquantel

Since the 1960s, there have predominantly been three classes of broad-spectrum anthelmintic drugs used to control helminths in mammals: benzimidazole/pro-benzimidazole (such as fenbendazole and febantel), tetrahydropyrimidines/imidazothiazoles (such as pyrantel, morantel/levamisole), and macrocyclic lactones (such as ivermectin and moxidectin). Emodepside belongs to a relatively new class of anthelmintics (depsipeptides) which achieve their antiparasitic effect against nematodes by a novel mechanism of action. Emodepside acts at the neuromuscular junction by stimulating presynaptic receptors. Emodepside has been shown to be highly effective against a number of nematodes affecting a wide range of animal species. Its efficacy against gastrointestinal nematodes of cats has been extensively studied. Additional studies in sheep, cattle, horses, and dogs have shown emodepside to display effective anthelmintic activity against trichostrongylids, ascarids, hookworms, trichocephalids, large and small strongyles as well as respiratory strongyles. Importantly, emodepside was reported to show some efficacy against nematodes resistant to ivermectin, benzimidazoles, and levamisole in sheep, and nematodes resistant to ivermectin in cattle.

The anthelminthic activity of praziquantel was discovered in 1972 in the laboratories of Bayer AG and was followed up at the German pharmaceutical manufacturer E. Merck. The mechanism of action is through the induction of tetanic muscular contraction and vacuolisation of the integument in cestodes and trematodes. The severe contractions observed in cestodes appear within seconds after exposure to praziquantel and this is soon followed by the loss of sucker concavity. As rapidly as 5 minutes after exposure, major changes in the syncytial integument are present in the area of the scolex and strobila. Integumental lesions are likely the result of the interaction of praziquantel with cutaneous phospholipids and proteins. Ultimately, these changes lead to the reduction of glucose intake and accelerated depletion of energy reserves. Praziquantel is a broad-spectrum anthelmintic drug used in human and veterinary medicine; it ensures reliable control of trematode infestations [blood fluke, liver fluke (except Fasciola hepatica), and lung fluke] and all stages of intestinal growth in cestodes.

Use of Profender® in Reptiles

A new treatment for internal parasites was shown to be safe and effective when administrated to a wide range of reptile species.10 Marketed under the tradename Profender®, this preparation is a unique combination of two active substances, emodepside and praziquantel: emodepside comes from a new class of active anthelmintic substances, while praziquantel, a convenient spot-on formulation for cats, controls cestodes.

Positive results were seen after administration of Profender® in a wide range of reptiles (snakes, aquatic turtles, agamids, varanids, and geckonids) found to be harboring high concentrations of nematodes belonging to the families Oxyuridae, Ascarididae, Strongylidae, Trichostrongylidae, and Capillaridae.10 Because of the thick stratum corneum of the epidermis of reptiles, it was necessary to administer four times the dosage of Profender® compared to that used in cats; approximately 0.56 ml for an animal of 1 kg body weight (equivalent to 22 drops/kg or 2 drops/100 g body weight).10 In a published report, it was recommended by the authors to apply the product to areas were the epidermis.is relatively thin (snakes: gular region or between scales; lizards: under armpits or skin folds of the groin area; turtles: prefemoral and gural fossa).10 In one report, dosages of 15, 30 and 50 times greater than those recommended for cats were administered to a variety of reptile species (snakes, geckos, and anoles) with no visible adverse effects.10

Profender® is distributed in three different sizes as single-dose pipettes (spot-on solution for small, medium, and large cats respectively). They all contain the same concentration of active ingredients; only the dose volumes dispensed are different. The product has a shelf life and is effective for several weeks after opening if properly sealed.

This new treatment method and product may find a wide range of applications in herpetological medicine: the “spot-on” administration is relatively simple, less traumatizing and reduces the stress generated by repeated orogastric intubation in “shy” lizards and turtles. Despite the initial encouraging results, caution in use of this medication should be exercised. Further research should be undertaken in a wide range of reptile species to verify the safety and efficacy of this promising drug, especially in affected animals.

Note: Toxicosis associated with fenbendazole (Panacur®) has been reported by Neiffer, et al.11 In this study, six male Hermann’s tortoises (Testudo hermanni) were treated orally with two 5-day courses of fenbendazole 2 weeks apart at a dosage of 50 mg/kg. In addition to health monitoring and stool examination, blood samples were collected to assess hematologic and plasma biochemical changes before, during and after the treatment period. Although the tortoises remained clinically healthy, blood analysis revealed several changes such as transient heteropenia, hypoglycemia, hyperuricemia, and hyperphosphatemia. Therefore, the authors recommended to 1) determine the hematologic and biochemical status of reptiles prior to administrate fenbendazole and 2) monitor hematologic and biochemical parameters of treated animals.

Literature Cited

1. Frye, F.L. 1991. Biomedical and Surgical Aspects of Captive Reptile Husbandry. 2nd ed. Krieger Publishing, Melbourne, FL.

2. Funk, R.S., and G. Diethelm 2006. Reptile Formulary. In: Mader DR. Reptile Medicine and Surgery. 2nd ed. Saunders Elsevier, St. Louis, MO:1119–1139.

3. Greiner, E.C., and D.R. Mader. 2006. Parasitology. In: Mader DR. Reptile Medicine and Surgery. 2nd ed. Saunders Elsevier, St. Louis, MO:43–364.

4. Hernandez-Divers, S.J. 2006. Reptile Parasites—Summary Table. In: Mader DR. Reptile Medicine and Surgery. 2nd ed. Saunders Elsevier, St Louis, MO:1159–1170.

5. Innis, C. 1995. Per-cloacal worming of tortoises. Bull Assoc Reptilian Amphibians Vet. 5(2):4.

6. Jackson, O.F., and J.E.Cooper. 1981. Diseases of the Reptilia, Vol. 1 & 2. New York, NY: Academic Press.

7. Klingenberg, R.J. 1993. Understanding Reptile Parasites: A Basic Manual for Herpetoculturists and Veterinarians. Advanced Vivarium Systems, Lakeside.

8. Mac Arthur, S., R. Wilkinson, and J. Meyer. 2004. Medicine and Surgery of Tortoises and Turtles. Blackwell Publishing, Ames, IA.

9. Mader D.R. 2006. Reptile Medicine and Surgery. 2nd ed. WB Saunders Elsevier Company, Saint Louis, MO.

10. Melhorn, H, G. Schmal, I. Mevissen, H. Harder, and K. Krieger.2005. Effects of a combination of emodepside and praziquantel on parasites of reptiles and rodents. Parasitol Res. 97: S64–S69.

11. Neiffer D.L., D. Lydick, K.Burks, and G.Doherty. 2005. Hematologic and plasma biochemical changes associated with fenbendazole administration in Hermann’s tortoises (Testudo hermanni). J Zoo Wildl Med. 36(4):661–672.

12. Stein G. 1996. Reptile and Amphibian Formulary. In: Mader DR, ed. Reptile Medicine and Surgery. WB Saunders Co., Philadelphia, PA: 465–472.