The Practice Success Prescription: Team-Based Veterinary Healthcare Delivery by Drs. Leak. Morris Humphries

Thomas E. Catanzaro, DVM, MHA, FACHE, DACHE

Why Book Number Thirteen?

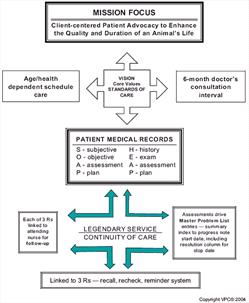

Click on the chart to see a larger view.

| Figure 1: Wellness Programs & Practice Liquidity |

|

|

| |

The veterinary profession is at a crossroads of healthcare delivery. Most practices have inadequate liquidity to pay for the quality staff that modern healthcare delivery requires. The quality of care has improved dramatically over the past couple decades, yet the fees and delivery modalities are still tainted by the pennies-per-hundred-weight (cwt) mentality of the heritage of farm animal practitioners. Many companion animal practices are still linear, doctor-centered, curative medicine delivery systems and unable to shift comfortably to a staff-based model of wellness care.

Our veterinary teaching hospitals have become tertiary care facilities, allowing a quality education to developing students, while teaching delivery habits that do not easily fit into a community-based, companion animal practice, or a production animal mixed practice on the farm or ranches of a large geographic region.

The average companion animal veterinary practice has a linear schedule, with the single column appointment log and single consultation room, for the outpatient doctor who attempts to divide time between inpatients and outpatients in a moment-by-moment decision sequence. The staff usually follows like ducklings, being sucked into the vortex caused by our crazy set of habits, which requires a doctor to be n all parts of the hospital at all times. We know it is a crazy life, but most practices have not seen the alternatives, so they continue to repeat the past.

There ain't a hoss that cain't be rode.

There ain't a man that cain't be throwed.

I started out in Montana's Gallatin Valley, training horses, never breaking them, just gentling them. An old California horseman named Bob Miller (no, not our DVM) took pity on me and showed me the gentling techniques. They all hinged on understanding the horses, their needs, and their responses to outside stimuli. Was it "horse whispering"? By today's fad terminology, yes, I guess it was.

When I finally enrolled at Montana State College, it was as a general agriculture student, since I did not know what specifically I wanted to do in life. What can one expect from a Midwest kid, who just spent summers in the Michigan farmland, picking blueberries for the pallet payment income? My Sigma Pi Epsilon fraternity brothers ensured that I learned bull riding, since I was the only agriculture major in the house. I really did not do too badly for the two years I tried it as a collegiate sport.

As a sophomore, I focused my academics on range management, and I won the First Place blue ribbon in the range management competition that spring. I knew my dirt and weeds, but it did not excite me. I did win my "breed" in the horse division of the Little International my sophomore year, but I did not win the species division my first year showing. This was the second year I was working on a horse for the Little International, so I actually won two First Places that spring: One in the horse division and one in range management.

So I changed to agricultural production and I really enjoyed the lambing barn, when I was on that rotation. There was joy in grafting a triplet on a single lamb ewe. Although I had a big hand, I did pass the exam and received my inseminator's license for beef cows, then made some good money doing artificial insemination. But then my counselor informed me I would have to marry a rancher's daughter to ever make agricultural production a profitable vocation. I immediately transferred to Animal Science with a genetics major.

During my junior year I won the Grand Champion Showman at the Little International Livestock show. Since I was fortunate enough to win the Little International Livestock Show Horse Division two years in a row, some of the key agricultural faculty knew I had some livestock skills. Even though I went on to become the Grand Champion Showman for all species in the third year of competing, I was still looking for my vocation. The Grand Champion Showman was traditionally awarded the person's job of choice at the now renamed Montana State University Agricultural Department, so I selected the horse barns and all the wonderful critters I had come to understand so well. This allowed me to share my new skills and the teachings of Bob Miller, my mentor, and Charles O. Williamson, author of Breaking & Training the Stock Horse, with many students in horsemanship classes, including some Crow and Blackfeet, who had lost the skill of "gentling horses". I was teaching body language of the horse, organizational behavior of the horse, and leadership of the horse. Yet, I never really understood the business extensions of what I was doing, other than it worked well and a bond of trust was formed with the horse.

It's taken almost my entire life to begin to understand the tremendous power that can be leveraged when people's individualism, creativity, and wisdom are unleashed. This is the art and science of organizational behavior. What is most interesting to me, as a student of people, management, and leadership, is that most veterinarians still do not get it!

Never approach a bull from the front,

a horse from the rear,

or a fool from any direction.

The pre-veterinarian takes years of undergraduate studies to acquire some foundation of basic education knowledge, then is accepted into a veterinary school. The first year provides the basics of the body, how it works, what happens to keep it running, and what one should be expected to find in a healthy animal. The second year is the "-ology" year, learning diseases, parasites, and pathophysiology pathways. Yet, we still have not touched an animal. The third year sees us take the baby steps, the surgery lab, the palpation labs, and even some real-world ambulatory trips into the real world. Our fourth year is the rubber-on-the-road year. We were in clinics, in surgery, and actually talking to real live clients. Then they present us our degrees, so we can go out there and "practice" until we get it right.

A practice owner learns management by signing a mortgage, not unlike the new receptionist, who is handed a name tag and told to go answer the phone. For some reason, the time it takes to gentle a horse, or the time it takes to become a veterinarian, or even the time it takes to develop a super client relations specialist at the front desk, is never applied to developing leadership and/or management skills by most practice owners, doctors, or even practice managers. To make matters worse, when a practice is evolving to the next level, most practices rush the staff and kill the energy of the change, without even understanding what they have done. On so many of our consults, the owner's number one delegation style is abdication. Metaphorically, the owner drops the reins and expects the horses to intuitively understand where they are going.

The Budweiser Clydesdale team pulls a wagon filled with beer. Well, not really. Those are just facades, with nothing in the middle, to keep the "hauling" task easier. And the team does not actually pull the wagon, just the wheel horses, who are the ones closest to the wheel, pull the wagon. The front six are for show and are learning the patterns of the show ring. Take a close look at those wheel horses. They are the muscled heros of the team and have the bulk of the pulling tasks. Again, not unlike practices where everyone supports the doctor.

In companion animal practices, we are leaving the doctor-centered practice and moving quickly to the client-centered practice, where everyone must be patient advocates. This requires a "healthcare delivery team". Here are the most common practice challenges we see:

Team building must occur concurrent with mission-focused patient care.

Team building must occur concurrent with mission-focused patient care.

Teams are built on inviolate core values of the leadership.

Teams are built on inviolate core values of the leadership.

Inviolate core values tend to produce inviolate standards of care.

Inviolate core values tend to produce inviolate standards of care.

Most veterinarians are not comfortable with a single standard of care in a multi-doctor practice.

Most veterinarians are not comfortable with a single standard of care in a multi-doctor practice.

Most staff require a single standard of care in a multi-doctor practice to allow them to support the practice, rather than supporting individual doctors.

Most staff require a single standard of care in a multi-doctor practice to allow them to support the practice, rather than supporting individual doctors.

The American Animal Hospital Association Compliance Survey showed that when clients accepted needed services for their companion animals, the problem was in the practice, not with the client.

The American Animal Hospital Association Compliance Survey showed that when clients accepted needed services for their companion animals, the problem was in the practice, not with the client.

A team is not built in a day. The wellness basics must be taught before the pathology, and these must be learned before the delivery model is implemented.

A team is not built in a day. The wellness basics must be taught before the pathology, and these must be learned before the delivery model is implemented.

Mission focus is first, team development in meeting mission needs is second, and consistent client-centered service from a set of core value-based standards of care is the methodology we use to leverage the doctor's time.

Mission focus is first, team development in meeting mission needs is second, and consistent client-centered service from a set of core value-based standards of care is the methodology we use to leverage the doctor's time.

For the mixed animal, ambulatory types reading this, if you don't have a driver, get one today. Nurture that person and allow him/her to part of your team. Not only is it usually good for at least fifteen to twenty percent more net, it allows you to be done with the day by the time the truck returns to the barn. Phone calls and medical record completions occur between the places you are servicing. Since your driver recorded everything you did and dispensed while you were on site, all you need to do is add a few professional assessments and sign the medical record. And best of all, your driver restocks the Bowie box, washes the truck every night, and ensures it gets regular maintenance, all according to the practice's plan!

Men from the range and barbed wire have their good points.

Now for some sage advice, folks. Envision gentling a horse. You probably have seen it on public television. You take a horse that has never been ridden and put it in the round pen. Yes, the halter can stay on if you have a solid-wall, round pen. You enter the ring and the horse starts to dance. You know your body and gestures will be the communication, not your words. The horse finally starts "going the distance". That's the usual distance needed to outrun the common predator. In the beginning, we know the horse perceives us as the predator, and it is the normal "flight reaction" we are seeing. The round pen prevents the "fight reaction" of a cornered horse. This anxiety is needed. That "discomfort" is the first element needed for change to occur, for human or horse.

For the Record, the round ring pen is nothing new. They have been on most western ranches since pioneer days, often made from logs. Charlie Russell, a famous Montana artist, put them in some of his paintings. I have even seen some round rings dug into the ground on the prairies, where there was not much building material. The usual use was linked to a large tree trunk standing in the center, with deep grooves worn into it by ropes used to dog-down the wildest of horses.

Just a couple of quick wraps on the snubbing post, you could crash the strongest horse to the ground. These horses were restrained, blindfolded, and broken into submission in most of these round pens. Most of these round pens carried the smell of fear and death. On some ranches, there are notches or marks for the horses that died, and other marks for the riders who died. Round pens were not always the safest ranch place to be.

The round pen is where two entities come together. It is here we start the "participative process" through a series of dominant postures and motions. It is Horse Communication-101. The human must now become a friend, rather than a predator, in that small horse brain. Power is needed to be a herd leader, and that is what the horse needs, a herd (team) for comfort. This is where experience, confidence, and savvy come into play by the person gentling the horse. Horses fear isolation, just as most people fear isolation. Prey herd animals always fear isolation. The gentling trick is to convince the horse that there are no claws or teeth, only a herd leader, the in-the-know, protector of horses. This is seen when the horse approaches the horse trainer and wants to follow or stay closer. It takes about twenty to thirty minutes for most horses. It takes ninety to one hundred twenty days for most people.

To create trust is the mandate of any herd, on any team, or in healthcare delivery. When the herd leader, the team coach, or the practice doctors are seen as allies, then the group will follow. The willingness to work must be harnessed. Without it, no gentle persuasion will ever be effective. The baseball coach needs a team that want to improve their skills. The herd leader needs a group that protects each other and follow well. The practice doctor needs skilled veterinary paraprofessionals, who have pride in their practice, doctor(s), and themselves.

Trust gives me my freedom and my fear takes it away. - Jack Gibbs

I remember when I learned how to do my first "Flying W", and I still have my one hundred-foot, one inch diameter, cotton rope. I have always known how to tie a bowline on a byte. The byte equals a bend in a rope, such as in the middle for a Flying W. So, the Flying W was a fun application. I could gently cast a horse by myself, after threading each fifty-foot end on each side behind the hock, through the neck bowline, then bring the ends back behind the horse and apply steady traction. The horse just sat down. It was cool. Then some old ranch hand showed me the "Running W whoa rope". It was a hideous affair, using half hobbles on each front pastern, running the ends through the stirrups, so when standing behind and pulling, the front legs were pulled up to the chest, instead of the hind end, like the Flying W that I was so proud of being able to use. The "whoa rope" was a simple task of hooking up the ends of a rope to the front hobbles, sending the horse away at a speed, yelling "whoa", and pulling on the two ropes from behind. The horse always came crashing to the ground, often hitting their muzzle, sometimes breaking teeth or legs. But if the horse survived eight to ten repetitions, it sure learned to "whoa". This was not horse gentling, and I would not allow the "Running W whoa rope" to be used by any of my students. Yet, in the olden days, before the expanded formulary, occasionally I used the "Flying W", when I needed to cast a horse that could not be drugged into sedation for treatment.

Another of the old styles of Montana horse breaking was "bucking-out the fear", and sometimes crashing a catsup bottle over the head of the horse if it tried to rear. This "spiritual death" technique of breaking was the worst thing I ever saw. I knew that there must be a better way. I vowed that I would find it, and I would promote "gentling" over any form of "breaking".

Years later, I did the same with the Promise© and Gentle Leader© head collar for dogs. I assisted for years as a pro-bono consultant and user, even when there were only nine sizes and one color, to get the head collar accepted. Why is the only animal we train by choking "man's best friend"? Why can I control a fifteen hundred-pound horse with a halter, yet need to jerk-choke a dog? Because I can? Because the cave man used that technique? We all know better. But in practice, how many times does the doctor or manager threaten and yell, rather than provide safety, belonging, and compassion to the group members?

Admire a big horse, but saddle the small one.

We introduced "high density scheduling" almost a decade ago, which means to work two or more consultation rooms out of sync with an outpatient nurse technician team. Then we developed a five-phase training plan that advances all the zones in the hospital, which included doctor, client relations, outpatient nursing, inpatient nursing, and animal caretakers, in a similar baby-step manner.

In this book, I give it a new name, since it is not a "high density" system, but rather a team-based system of multi-tasking. All we ask is that the doctors say "We trust you at this skill level" before the team advances from one phase to the next.

What is the big deal? In most cases, the doctors do not have enough time or tenacity to say five separate times over sixty to ninety days of staff development and training, "We trust you at this skill level. " What is the inhumane training factor of this neglected process? Managers expect the staff to change delivery methodologies without regular and positive recognition, and then expect them to support a doctor who has not been involved in the delivery modality changes. Seems as bad as a snubbing post to me!

It is not a simple task to take that large step into a new kind of relationship, whether it be between animals or between people. People always expect you to revert, and animals instinctively respond to inappropriate gestures and body language. We are truly pliable. If we want to "talk" to horses, we learn the horse's language, not expect the horse to do the same. After all, our brain is bigger and better. If as a leader we want to build a practice team, we learn the staff's language, not the other way around.

Any rider who brags he ain't been throwed sure ain't forked no bad ones.

Robert Redford has made "horse whispering" into a lucrative business for many horse trainers who gentle horses. The time was right for his movie The Horse Whisperer, and society responded to the anthropomorphic hope.

When Bob Miller taught me how to gentle horses back in the early 1960s, I absorbed his knowledge as if I was a sponge. Now I realize that the same issues apply to the practice leadership principles I have written about over the past twenty years:

Always work to cause your horse to follow the path of least resistance. Then place an opening for the horse to pass through, so the path of least resistance becomes the direction you want him to go.

Violence is never the answer

It is not a good trainer who can cause his horse to perform. It is a great trainer who can cause a horse to want to perform.

There is no such thing as teaching, there is only learning!

Many people watch, but few see. Less understand.

If your horse wants to go away, don't send it away a little, send it away a lot.

Everyone has the right to fail.

No blade of grass has ever run from a horse. Do not use food as a reward.

No one has the right to say, "You must!"

It is my belief that no one was born with the right to say to any other creature, animal, or human, "You must or I will hurt you."

Make it easy for him to do it right and difficult for him to do it wrong.

The horses are talking. Just listen.

A horse trainer must keep in mind the idea that the horse can do no wrong. That any action taken by the horse, especially the young unstarted horse, was most likely influenced by the horse trainer.

It was a surprise a few years ago, when we received a Montana postcard at our consulting office, and all it said was, "We did not have the heart to tell Bobbie that the Tom from Montana who was the horse whisper was actually an Italian kid who came from Chicago". Seems some of the Crows I had trained in gentling ended up on the wrangler staff of Redford's movie, as he wanted to hire Native Americans. Bobbie played the role of Tom, a horse whisperer from Montana. It was too funny, trying to explain this thirty-year legacy to the office team. It makes me feel real warm and fuzzy that some of my horsemanship students remember our times together with fondness and humor.

Since Bob first shared his wisdom and skills with me in the early 1960s, I have never rushed a horse in its development. No trainer would ever start a green horse with a flying change of leads. We work at the halter before we work under the saddle. We build basic skills and trust, so they will not buck, when on a narrow mountain trail. They wait for us to lead them to safety. This "choice" was established early as we built "trust". On rare occasions, I have had horses other people have ridden, and they may try to sunfish or buck on me, when they are not happy. My training saddle was a metal tree, three-quarter single rig, with undercut swells, and four-and-half-inch cantle. And as I would pull the horse over, stepping out of the saddle, I would guide them down and sit on their neck, talking to them. Lying down "trapped" is a very scarey position for a horse. They must learn my voice means safety early on in the process. When we get back up, we walk awhile and cement that trust before I get back into the saddle, but I always get back into the saddle. I always trust that the horse will understand that together we are better than alone. In most all cases, we've reached agreement.

A cow outfit is no better than its horses.

When starting a horse, I never will allow anyone to hit, kick, jerk, pull, or tie a horse to restrain it. Sure we request that the horse perform certain maneuvers, but the animal must not be forced or demanded. A horse is a flight animal. When inappropriate pressure is applied to the relationship, the horse will most always choose to leave, rather than fight. Eyes-on-eyes in a green horse will most always cause flight. It is perceived as predatory behavior.

Initially I keep my shoulders square to the horse and my eyes stay in direct contact at all times. After less than a half of a mile around the round ring, the horse will try to negotiate with its predator. It requests a truce of sorts. When it stops, I am already squared to it, looking eye-to-eye. I then watch for the ear to point at me. This is usually the first step in horse negotiations after flight. Then follows the tentative step toward me, coming off the wall and toward the center of the round ring. Hopefully, my squared stance and eye-to-eye contact will keep him thinking. I watch for the licking or chewing phase. This is sort of a "no fear" gesture, as he does not feel a true predator threat any longer. When his head drops, I know we have negotiated my leadership into his safety zone. I move my eyes away now, turning slightly away with my shoulders, about forty-five degrees from the axis of the horse. This is my trust towards him, and time for his "choice" to come to me. Standing motionless is very important at this juncture, and I let him nudge me, most often in the back.

I must respond in a safe manner, so I round my shoulders, cast my eyes between his front feet, close my fingers, bend my wrist, and slowly reach out to rub him between the eyes. This is a reward from the leader. If the horse returns to flight, when I start to rub, I let him do the quarter-mile-plus needed to start the steps over again. Never short-cut the first four gestures. When I am successful with the rub, the horse will generally follow me around the ring in any serpentine pattern I choose. I reward him for the positive actions, yet put him to work if he does something negative. "Work" in this manner is asking him to accept certain responsibilities. And as long as he trusts me, we will work our way through a series of common goals. One of the first goals is to allow me to rub him high on the back and low into the soft flanks, which are predator attack points. I stroke, then walk away, so he knows I offer no pain or threat. Later, I will pick up and put down each foot, again walking away, when I am done. I use a burlap bag to rub the back and neck. Then I use it for a soft flapping stroke over the back, then down the legs. I walk away again to show him that this is okay, and I am a safe creature. Saddle pad comes next, then saddle, followed by the bridle. Sometimes the curb bit of the bridle takes the horse's mind off the saddle weight. This diversion can be to my benefit. The rider comes last. If he balks at any point, I gently but firmly push him away from me, and start the round pen perimeter running program again.

When I redesigned the horse corrals and chutes at Philmont Scout Ranch, outside Cimarron, New Mexico, I asked that all corners of all paddocks have a forty-five-degree pipe welded across each corner. That way no horse would experience a trapped feeling, as the young riders guided their horses around the perimeter for the first time. Inflicting pain or allowing violence, such as jerking, pulling, or otherwise cowboying the bit with the reins, cannot be tolerated with these young riders. So we must keep them from having to be put in that position. This is the secret of true leadership. Create a situational environment of no trauma or stress, and one that allows everyone to elect to do the right thing, because it is the path of least resistance. Then I can say "well done" as the reward to these young riders.

Sure, most horse methods are physical, while most people methods are psychological. Both are rooted in the psychology of acceptance, which will be predictable, productive, and effective. We all know there is never a second chance to make a first impression. Yet, when we get a new candidate for the team, how often do we make the excuse, "We will get that training later," so that we do not need to adjust our paradigms immediately?

It's a sorry cowhand that'll ride a sore-backed horse.

Is the horse rub between the eyes the same as a handshake? How many first impressions come from that simple touching of flesh encounter? When shaking hands, are genuine welcome and warmth conveyed, or is there a lack of commitment and caring, or worse, a painful first encounter. Again, eye-to-eye comes into play in people. Whereas with a horse, there have been preceding steps that allow me to look down. When greeting people, direct eye-to-eye contact is needed. In fact, in most all communications between people, seventy-five to eighty percent eye-to-eye is needed to retain the perception of being "in touch" and "caring". Eye-to-eye with a green horse says, "Go away." With people it says, "Communication will follow."

Horses go from suckling on their dam, to chewing and licking. They are continual grazers. That is why it is one of the key steps in horse communications. Does the "Let's have lunch" express similar comfort, compared to, "I want you to schedule an hour for me in my office, we need to talk"? Which allows more safety in communications? Having a meal with someone is a major gesture in our society, regardless of breakfast, lunch, or dinner.

In horses, bowing the head is giving leadership to the trainer. In Japan, the one who bows the lowest provides for the other to speak first. Both the horse and the lowest bowing Japanese are saying, "Please set the agenda for this meeting, and while I am not to be taken lightly, someone needs to lead, and I would like you to assume that role." This may sound overly polite to most Americans, but horses and the Japanese are very polite in their communications.

Horses cannot contrive, but people do. Horses never fake it, people do! Is this similar to nurturing a team member and seeing if that new colleague comes to you for assistance or extra knowledge? The biggest practice team challenge here is that the players have different background experiences. I find some have been "burnt", and trust is hard to give or receive, with any level of respect. What I see most often is the inference that others have the same social values as you. Therefore, the cold doctor has a cold staff, and the warm doctor has a warm staff.

It is like an experience I had in Belize, during my last leadership course in the jungles. The British had sunk wells along the major travel routes, and I was sitting at one, taking a short trek break. There was an elder there also, just sitting. Along came two British hikers, who asked the old man, "What are the people in next village like?"

The old man asked, "What were they like in the past village?"

The hikers responded, "Unfriendly and really kind of cold to us."

The old man said, "Alas, they are very similar to the next village."

I looked over at the old man and said, "I have just come from that village, and they were not only friendly and warm, they shared of themselves with me. Why did you say they were similar to that previous village?"

The old man smiled at me and explained,"Our people are very similar in these villages, and life is hard. I have found it is the perception of the visitor, and not the village, that sets the stage for acceptance."

I thought about that and said, "So the people in the village, where those two British hikers came from, will accept me? Be warm and friendly?"

The old man looked at me and said, "They will be as you perceive them to be, no more and no less. They live without plumbing and without electricity, but they have attended our mission schools and have a good brain. They welcome visitors as visitors welcome them."

I thanked the old man, filled my canteen, and trekked off to the next horizon, and the village in question. As I reached that village, I found they were as warm, friendly, and communicative as the last, and they also shared of themselves with me. It was a discovery that I have always known down deep, but had not verbalized. Other people are only a reflection of my expectations.

When I was in Montana, one of my favorite sayings was, "A good horse don't come in no bad colors." I had a string of Appaloosa yearlings I was gentling, and I do have beliefs about color breeds. This was back in the early 1960s, please understand. The horses with which I won the Little International Stock Show both years were polo thoroughbreds from the Sun Ranch, with shorter legs, were quicker turning, and warm bloods. Back then, we never saw an Appaloosa that had a great brain, although they looked pretty. But again I say, "A good horse don't come in no bad colors." Same for people, if you hire for attitude and forget the breed type, is in résumé stories. If they have the attitude, they will accept training and increase their skills and knowledge. If they have some sort of skills or knowledge, but a poor attitude, they will not likely increase in competency or productivity, without a major life-changing experience.

It is easier to catch a horse than to train one.

A rider is always ultimately responsible for the horse, a commitment akin to leading a veterinary healthcare delivery team. You found these people, you hired these people, you trained these people. They are a reflection of your values. Every practice has the staff it deserves, just as it has the clients it deserves. Staff and clients have been selected by eliminating those you do not want. I would prefer to think that there is mutual respect and nurturing in every team, but I know for a fact that people are not always honest with themselves, when in a stressful environment. They need the money, so they grit their teeth and just "fake it" from paycheck to paycheck.

Horse training is response-based, not demand-based. Joining is the ultimate group development phase. As a trainer or leader, you open the doors of opportunity, while maintaining a safe environment. Training/learning has been completed, application has been verified, and evaluation says competency has been reached. You are confident that the horse, or person, has the trust, knowledge, and skills to cross over to the next level and still be effective. (See Building The Successful Veterinary Practice: Leadership Tools, Appendix B, Leadership Skills Handouts, Group Development.)

Most horse people have had their favorite horses, as most students have had their favorite teachers. Both these favorites have usually been based on the "ability to learn", rather than the ability to teach. Within our veterinary healthcare teams we will also have our favorites. Usually they are the ones who have learned and kept learning, the ones who can be trusted to put the client and patient before their personal bias. We must acknowledge that favorites are based on their personal response to the needs of the practice, not tenure nor demands for excellence by others. Individuals have characteristics and needs, just as groups have characteristics and needs. The true characteristics never change, but needs always change, based on what has been fulfilled and what has been learned. A good leader is always restoring balance to the mentoring equation between the "needs of the group" and the "needs of the individual". Balance is only a passing point in time.

Fear and mistrust occur with a horse when someone is unfamiliar with the animal that is so much larger than the human. This is an individual person's problem, not a horse-caused issue of the person's life. Some choose to learn about horses, while others avoid horses. Horses do not hurt without a cause. They prefer the flight reaction. In humans, fear and mistrust are most often a learned response to a familiar situation involving a boss, wife, parent, etc. Some leaders choose to learn about their people and their needs, while others demand the person change to meet the environment, regardless of disharmony. What we know from horses is that if I remove fear and threats from the environment, the learning and innovation spiral upward. What we know from veterinary practices is that change causes major fear. And if change comes with threats from within the environment, rather than nurturing, flight often occurs within the staff.

If a cowboy gets bucked off a rabbit-shy horse, he gets even.

He makes the horse walk back to the ranch all by himself.

Change must occur without production loss in today's veterinary environment. There is no time to stop a practice and "build a team", just as there is no time for a doctor to ignore a scheduled appointment. The average practice day is a series of schedules. Time management is just sequencing events in the most effective manner. This must be done by staff, not doctors.

Horses must change as the trainer asks them to learn new skills, and that's accomplished most effectively in very small incremental steps. Why is it that in veterinary practices change is so often an arbitrary top-driven mandate, without the needed training, or without sequential events, which allow each small improvement to be recognized and celebrated?

The body language of horses offers profound lessons for communication between humans. Yet, it took me years to realize that what I learned about non-verbal communication with horses is what I was using with business relationships. Entering a veterinary practice, I can detect unrest, unhappiness, isolation, and pride almost instantly. It is part of my diagnostic savvy. Stanford verified this with a very well-publicized study, with a sample size large enough to be significant, where words were only seven percent of the communication message between people, the "tone" used was thirty-eight percent of the message, and non-verbal aspects accounted for fifty-five percent of the communication between people. In the wild, silence is paramount for horses, so very subtle body language is the primary communication. A keen sense of smell and great eyesight aids the horse in effective communication.

You don't need help falling down, but a hand up sure is welcomed.

In autism, Delta Society has provided research that a black and white animal is a very successful aid in breaking through the non-communication so common with autistic children. We know that autism is a neurological dysfunction, with many levels of severity. The cause is not fully understood yet, since brain over-activity can have many causes, including under-development of other areas of the brain. Children are born with autism, it is not an infection or a disease with a dramatic cure. Like autistic children, horses appear to think spatially, or in pictures. This is not unusual for even unaffected people. I can remember practice floor plans far easier than I can remember names of the architects or doctors planning the structure(s). When an autistic child is doing hippo therapy (horseback riding), there seems to be an extra connection. Calmness is almost instantaneous after a high-anxiety autistic is placed on the horse, as visual thinkers usually communicate better with animals. In fact, an autistic child shies away from any eye-to-eye contact, except when working with a black and white animal. Autistic children are very sensitive to body language -- almost as astute as a horse -- but most of society has not tried to understand these young people with the same intensity we have with horses. Horses and autistic children both thrive on the routine. They want an environment where they know where everything is. Unwanted touching causes fear. In fact, autistic teenagers, who the books claim are not treatable, have been greatly affected by black and white animal therapy. In some cases they have relearned to navigate shopping malls and escalators.

Effective communication in people is defined as the getting and giving of information. Yet, in many veterinary staff meetings, only the doctor or manager talks, and the people listen. So, after a short time, staff meetings cease being needed. The benefit we have in veterinary practices is that the group is most often like-minded, just as horses are. Staff are there because it is a form of a "calling", they want to tend to the animals, and will work for poverty wages just to be in that environment. This is the key factor that makes poor leadership workable in veterinary practices, just as the herd need for safety allows a band of horses to stay together.

You sure gotta control yerself before you kin control yer horse.

When I allow the horse to run around the perimeter of the circle pen, I am allowing that horse to make free choices within the limits I have set beforehand. I want the horse to have the free choice to come to me. With staff, inviolate core values and standards of care form the same limits. They allow the staff to come to the leader with conflicts in application, as well as alternatives for solution, such as innovation and creativity. Without the round pen, the horse would bolt away from my environment. Without core values and standards of care, veterinary healthcare delivery teams are operationally lost, thus unable to respond to the clients and patient needs.

Inversely, horses come with instinctive baggage and gain baggage throughout life. The horse instinctively has two main functions in life: To survive and to reproduce. They are flight animals, who fight only when there is no alternative Horses learn that certain situations represent danger and do not repeat that "picture" in their minds or lives without reacting.

I was riding a palomino fox trotter one afternoon, after a long consult day. The horse belonged to a consulting partner (client), and she offered him to me, since he was "hard to handle". We rode down the lane, came to a stream, and the owner said, "He won't cross that stream. You need to go down to that culvert crossing."

We sat at the stream, and I tried to get a feel about this gelding. So I asked the horse to cross the stream, and he did directly, though I did get a couple of snorts. As we rode down the forested trails, the owner said, "Be careful, he loves to rub you off on trees."

For me, this big gelding stayed center trail. Now I must admit, I ride very straight up and over the point of balance of a horse, which came from my training days, although my elbows do not flare out like Glenn Ford's have in the movies. I felt we were a good pair. After a few more warnings that never materialized, the owner just enjoyed the ride. We got back to the barn, then started unsaddling and brushing down the horses. The owner said, "You know, this horse has even been given to biting me, and it was a gentle giant in your hands. Amazing."

Within thirty seconds after that comment, the palomino gelding turned and bit her. Yep, horses carry baggage, just like people. But often horses are far harder to change than people, because the horse's behavior is based on instinctive pictures and experiences.

Violence is the last refuge of the incompetent. - Isaac Asimov

This was the strongest lesson that horse training ever taught me. It is how I became interested in veterinary school. During the spring quarter of my senior year at Montana State, I was mentoring a group of sixteen young adults in preparing their horses for the Little International. One ranch cowboy decided to snub the horse up to the pick-up and teach it to lead by using the three hundred eighty-nine horsepower of a V-8 truck. By the time he was done yanking this horse down the gravel road, the jaw had been "nerved", the lower lip was flapping in the breeze, and we had knee abrasions. I called in the Montana State University extension veterinarian. Jack Catlin. While working with Dr. Catlin, there was an epiphany in my existence and inner being. This is what I really wanted to do with my life: To be a veterinarian.

When a young man graduated from college in the mid-1960s, he had only two choices: The blue suit or the green suit. In the blue suit, I could swim to shore, or jump out of an airplane, while in the green suit, I could swim to shore, or be in a hole in the ground. I selected the green suit, where I could walk out, and accepted a commission in the U. S. Army.

In their infinite wisdom, and with my Agricultural Science B. S., the Army said, "You need to be in the Medical Service Corps." Thus started my military career. Three infantry unit tours later, one in Viet Nam, I decided it was time to go to veterinary school. All I had to do was get accepted. What the Army taught me was the practical side of leadership. Military officers in Viet Nam, especially at the forward fire bases, where I was stationed, those officers who did not understand being a "leader of men" most often came home in a body bag. Heck of a training incentive.

They say being in a war, as with a divorce, changes a person forever. I say we are all a composite of our environment, morés, our families, and our life style choices. Each choice is a life-changing decision, and each decision has a consequence. Either you live with the consequence, or you make another decision, which changes the first consequence for the next consequence. There is no abdication allowed with life's decision-based consequences. You picked it, you live it. Therefore this text:

Is designed to integrate all the publications VCI© has shared with the veterinary profession since 1997.

Is designed to integrate all the publications VCI© has shared with the veterinary profession since 1997.

Is designed to ensure a practice can leverage the doctor's time, producing better client service and higher patient advocacy.

Is designed to ensure a practice can leverage the doctor's time, producing better client service and higher patient advocacy.

Offers methods and models that drive breakthrough performance, but concurrently requires that old practice paradigms be left behind.

Offers methods and models that drive breakthrough performance, but concurrently requires that old practice paradigms be left behind.

Is designed to integrate all the practice staff into a single, harmonious, and proud veterinary healthcare delivery team.

Is designed to integrate all the practice staff into a single, harmonious, and proud veterinary healthcare delivery team.

Offers a look into the future, and shares alternatives, which must be addressed, as practices evolve into business models.

Offers a look into the future, and shares alternatives, which must be addressed, as practices evolve into business models.

Is designed to establish a liquidity, which will allow owners and staff alike to have a better quality of life outside the practice.

Is designed to establish a liquidity, which will allow owners and staff alike to have a better quality of life outside the practice.

Offers enhanced practice harmony and team competency techniques, at a level all will be proud of, when communicating with the community.

Offers enhanced practice harmony and team competency techniques, at a level all will be proud of, when communicating with the community.

Is designed to give leadership skills a new life in the minds of doctors, managers, administrators, and coordinators.

Is designed to give leadership skills a new life in the minds of doctors, managers, administrators, and coordinators.

Dr. Tom Cat

|

The Confession

Even after all I wrote above, I have had blinders on for most of my married life. It was a dumb persona from my childhood days. As I was getting my divorce, after forty-five years of marriage, I sought a life coach to ensure I addressed what caused my side of the equation to fall short. I have always been proud of being a hard-charging SOB, who gets whatever I set my mind to achieving, regardless of adversities and critics. The life coach was a past Army Ranger, who are hard-charging SOBs in the military. By the end of the first session with him, it was obvious. I needed to treat all the people that I love and respect like animals. Only a veterinarian would understand that statement. Speak softly, accept the nonjudgmental love, and nurture them into a common goal. Stop with the value judgments, and stop the confrontations for who is right. Work from where they are, advancing slowly, inch by inch, to a partnership of mutual respect. Interesting, isn't it? Tom Cat |