Norwegian School of Veterinary Science, Department of Companion Animal Clinical Sciences

Oslo, Norway

Ocular injuries include

Proptosis of the globe

Proptosis of the globe

Eyelid lacerations

Eyelid lacerations

Lacerations, ulcers and foreign bodies of the cornea and sclera

Lacerations, ulcers and foreign bodies of the cornea and sclera

Blunt trauma to the eye

Blunt trauma to the eye

Many general practitioners feel uncomfortable when presented with an ocular emergency, feeling that the matter should be dealt with by a specialist. However, referral is not always possible, and a time delay before treatment may cause irreversible damage to the eye. It is therefore essential for the general practitioner to be able to handle ocular injuries properly. Some basic knowledge on ophthalmic anatomy and function of the eye, as well as principles for ocular examination, is required. One should always remember that injuries within or around the eye are extremely painful. Thus, care should be taken to relieve postoperative pain. In addition, one should not forget that more than one ocular structure might be injured simultaneously.

Globe proptosis

Proptosis of the globe is one of the true emergencies in veterinary practice, which requires immediate action. Proptosis is in most cases a condition of brachycephalic dogs, but may occur in animals of any breed. What happens in brachycephalic dogs is that the eyelids are pulled backwards and get trapped behind the globe, while the globe itself changes position to a lesser extent. Proptosis in dolicocephalic dogs is usually accompanied by more serious ocular or periocular injury, and carries a poorer prognosis.

If possible, the owner may be advised to attempt to push the globe back into normal position during the first minutes after injury by gently pushing on the eye with a moistened cotton wool pad. During transport to the veterinarian, the eye should ideally be kept cool and moistened, but the animal is often too upset to allow this.

The severity of the injury should be evaluated. A poor prognosis is given if there is rupture of several extra-ocular muscles, if intra-ocular haemorrhage is present or if there is lack of indirect pupillary light reflex from the injured to the normal eye. A severely injured eye should be enucleated. If in doubt, it may be better to reposition the eye and give a guarded prognosis.

Principles for reposition include:

General anesthesia

General anesthesia

Systemic steroids intravenously, plus NSAIDs if kidney disease is not suspected

Systemic steroids intravenously, plus NSAIDs if kidney disease is not suspected

Lateral canthotomy. Most often the eyelids are too swollen to allow reposition without this procedure

Lateral canthotomy. Most often the eyelids are too swollen to allow reposition without this procedure

Flushing of the eye and conjunctival sac with ringer acetate or Betadine

Flushing of the eye and conjunctival sac with ringer acetate or Betadine

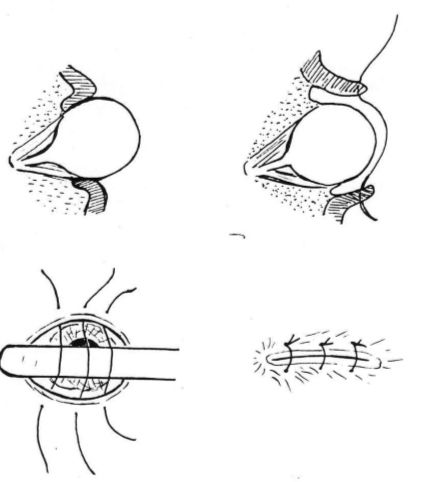

The globe should be repositioned as soon as possible by placing three to four holding sutures in the upper and lower eyelids. The eyelids are gently pulled forwards while the cornea is protected from the sutures with a scalpel handle as illustrated (Figure 1)

The globe should be repositioned as soon as possible by placing three to four holding sutures in the upper and lower eyelids. The eyelids are gently pulled forwards while the cornea is protected from the sutures with a scalpel handle as illustrated (Figure 1)

The eyelids are closed with the preplaced sutures, ensuring that the sutures do not penetrate the eyelids and rub on the cornea. A small opening should be left at the medial canthus to allow topical medication

The eyelids are closed with the preplaced sutures, ensuring that the sutures do not penetrate the eyelids and rub on the cornea. A small opening should be left at the medial canthus to allow topical medication

The lateral canthotomy wound is closed in two layers

The lateral canthotomy wound is closed in two layers

Atropine is applied topically together with topical broad-spectrum antibiotics

Atropine is applied topically together with topical broad-spectrum antibiotics

Continue with topical and systemic antibiotics plus systemic NSAIDs. In cases of intraocular hemorrhage the NSAIDs should be replaced with systemic steroids.

Continue with topical and systemic antibiotics plus systemic NSAIDs. In cases of intraocular hemorrhage the NSAIDs should be replaced with systemic steroids.

The sutures should be left in place for 2-3 weeks. After one week the most medial suture(s) may be removed and the eye inspected.

The sutures should be left in place for 2-3 weeks. After one week the most medial suture(s) may be removed and the eye inspected.

| Figure1. |

Repositioning of a prolapsed globe. |

|

| |

Eyelid lacerations

Lacerations frequently affect the rim of the eyelid. If the wound is fresh (i.e., less than 6 hours), as little tissue as possible should be removed. Old wounds may require reconstructive surgery. Lacerations of the medial canthus may include injury of the lacrimal system, which should be identified and cannulated with a thin Silastic tube before closing of the wound.

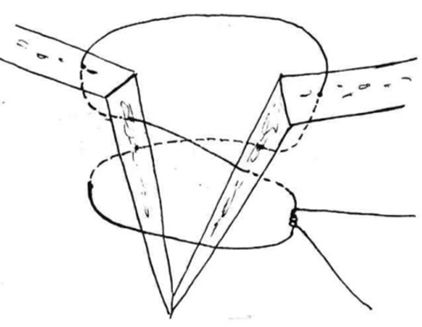

Eyelid lacerations are usually sutured in two layers. To prevent corneal irritation the deeper suture should not penetrate the conjunctiva. The first skin suture should be placed in the rim of the eyelid as illustrated (Figure 2), where after the rest of the wound is closed. Aftercare includes topical, if necessary also systemic, antibiotics plus systemic NSAIDs to prevent swelling and pain. One should be aware that intraocular structures might also be injured. Thus the eye should be subject to thorough ophthalmic examination and treated accordingly.

| Figure 2. |

Repositioning of a prolapsed globe. |

|

| |

Corneal wound healing

Dependent on the depth of the injury, corneal ulcers may heal by primary or secondary wound healing.

Epithelial injuries heal rapidly as follows: Epithelial cells migrate to defect after about 4 hours (approx. 1-3 mm/day). Mitosis is initiated to complete cell layering, and normal epithelial cell thickness is reestablished. Adhesion between epithelial cells and stroma occurs slowly.

Stromal injuries heal slowly and scar readily. Two to four days after the insult, vessels will invade the stroma from the limbus--usually at a rate of about 1 mm/day. There will be secondary formation of granulation tissue and later scarring. Some deep stromal ulcers may heal with migration of epithelial cells, without vascularization.

Descemet's membrane. If injured, Descemet's membrane heals slowly and scars readily.

Endothelium. The endothelium has limited mitotic or regenerative capacity in the adult animal. Cells will change shape and adjacent cells may spread into the defect. Endothelial damage may result in defective pump function with secondary corneal oedema.

Corneal injury

Emergencies of the cornea are usually traumatic or infectious in origin. Early diagnosis and appropriate therapy is necessary to prevent loss of vision, and response time may have a significant effect on desired outcome. The most commonly encountered corneal emergencies include deep or penetrating lacerations, with or without iris prolapse, descemetocele and melting bacterial corneal ulcers--most commonly secondary to Pseudomonas sp.

Properly administered corneal adhesive may be used for small, uninfected descemetoceles, while the larger require surgery, either with a conjunctival flap or with other material for reconstruction. Preoperative culture of the ulceration may be beneficial if infection is suspected, but most uncomplicated ulcers are routinely treated postoperatively with broad-spectrum antibiotics.

Prognosis for a successful result of corneal suturing is dependent on proper instruments, suture material and magnification. A thorough inspection is necessary to determine extent of damage and/or presence of any foreign bodies. Any laceration extending past the limbus, and especially those with exposed uvea, carry a poorer prognosis for a good visual outcome. Corneal rupture from blunt trauma also carries a poor prognosis for vision. Perforated corneal ulcers in cats usually carry a better prognosis than in dogs.

Direct corneal suturing with 7-0 or 8-0 Vicryl or Dexon is generally recommended for a descemetocele less than 3-4 mm in diameter, as well as fresh lacerations without tissue loss. Simple interrupted sutures are placed through 2/3 of the corneal thickness. If there is substance loss, a pedicle flap originating from the surrounding conjunctival tissue may be indicated. To cover the ulcer the flaps may be broad or narrow, long or short. One should be careful not to make the flap too long and narrow, as the blood supply to the tip of the flap may be too poor. Conjunctival flaps are sutured to the edges of the wound. Other methods of covering the ulcer include free conjunctival grafts, corneoscleral transposition and use of other material, for instance Biosist®.

Corneal perforation is typically accompanied by anterior displacement of the iris. If possible, it should be attempted to re-establish normal anatomic conditions of the anterior chamber, either with irrigation or with the injection of viscoelastic material in the anterior chamber. A prolapsed iris may be repositioned up to 24-48 hours after injury. If the iris is injured or impossible to reposition, the prolapsed part may be cut. This may result in a later synechia between the iris and cornea.

A small rupture in the anterior lens capsule may seal spontaneously, but a larger rupture with leakage of lens material into the anterior chamber causes a serious phacoclastic uveitis that is difficult to control. In these cases referral for removal of the lens through phacoemulsification is recommended.

It is essential to remember that:

Deep corneal ulcers may progress to perforation

Deep corneal ulcers may progress to perforation

Perforating ulcers are always accompanied by uveitis

Perforating ulcers are always accompanied by uveitis

If you are referring the patient to an ophthalmologist for corneal suturing, you should start uveitis treatment as well as giving antibacterial medication before referral, unless the patient can be handled by the ophthalmologist within a very short time.

If you are referring the patient to an ophthalmologist for corneal suturing, you should start uveitis treatment as well as giving antibacterial medication before referral, unless the patient can be handled by the ophthalmologist within a very short time.

Cat claw injuries are penetrating until proven otherwise

Cat claw injuries are penetrating until proven otherwise

Third eyelid flaps are not optimal treatment for deep or perforated ulcers, but may be used as corneal bandage when referring a patient to an ophthalmologist.

Third eyelid flaps are not optimal treatment for deep or perforated ulcers, but may be used as corneal bandage when referring a patient to an ophthalmologist.

Corneal foreign bodies

These may be found in the superficial or deep cornea or as an intraocular foreign body. Superficial foreign bodies can be carefully removed with the use of a 25g cannula, which is slid underneath the foreign body and the object lifted out. Deeper foreign bodies, for instance thorns, can be removed by securing the foreign body with two thin cannulas, one on each side.

Intraocular foreign bodies are removed through an incision in the peripheral cornea along the limbus. One should be careful not to cause unnecessary injury to the cornea when removing the foreign body. Aftercare after removal of foreign bodies is dependent on the depth of the injury, remembering that perforation of the cornea involves uveitis as well as risk of infection.

Blunt trauma

The effect of blunt trauma may vary from a small injury to severe intraocular hemorrhage and even rupture of the globe. A thorough examination, including measurement of intraocular pressure as well as funduscopy, is indicated to diagnose the extent of the injury. Typically, the veterinarian is presented with an animal with a "red eye". There may be corneal edema and a miotic pupil present. Miosis may indicate both pain and breakdown of the blood-ocular barriers.

Small injuries should be treated accordingly. Intraocular, as well as retinal hemorrhage, imply breakdown of the blood-ocular barriers. Uveitis treatment should be instilled, including mydriatic, steroids and pain relief. A ruptured globe from blunt injury carries a poor prognosis, and enucleation should be considered.